Ivor Arbiter

Ivor Arbiter

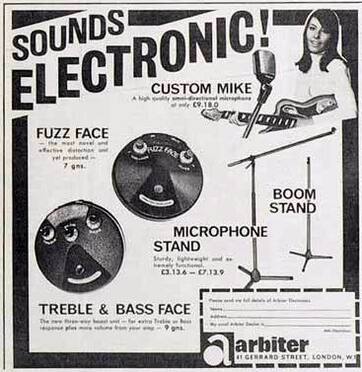

“Fuzz Face is the new fuzz box from Arbiter giving the ultimate in controlled effects”, reads the advertisement for the new Fuzz Face, presented in England by Ivor Arbiter in the autumn of 1966.

Ivor was an amateur drummer and ran three shops in West London, including End Drum City Shop on Shaftesbury Avenue and Sound City, which specialised in guitars and amplifiers and was located on Rupert Street. He was also known for having sold, in the early 60s, the Ludwig Black Oyster Pearl drum kit to Ringo Starr, on which he had ‘hastily’ drawn the Beatles logo with the dropped ‘T’, which later went down in history. In 1966 he founded Arbiter-Western.

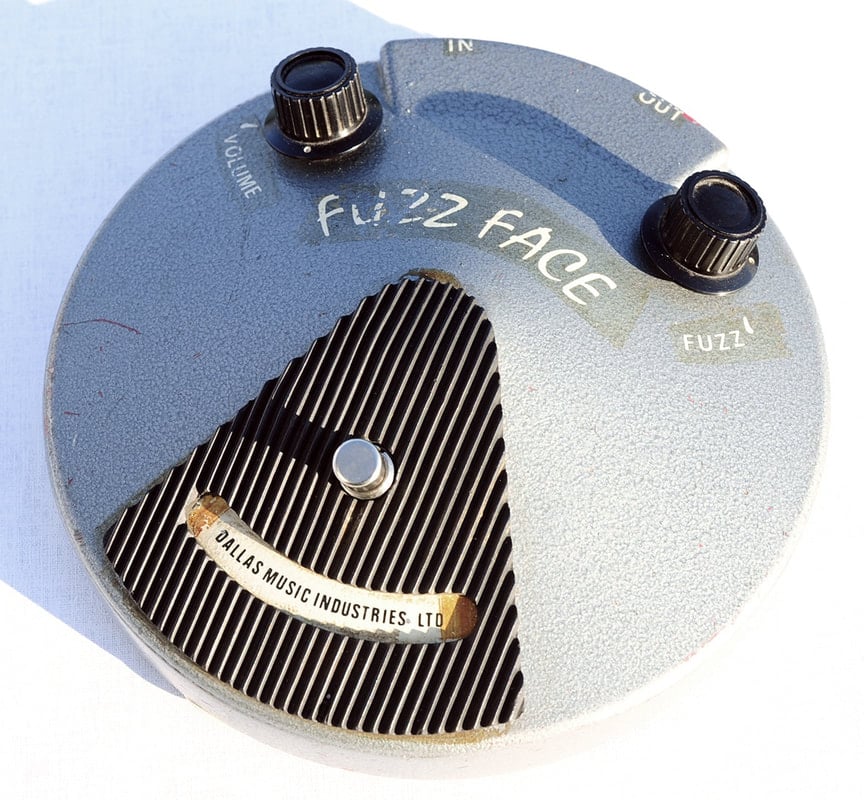

The shape of the Fuzz Face, which was completely innovative compared to the fuzz boxes currently on the market, was inspired by the base of a microphone stand and, with its two Fuzz and volume knobs, the switch and the semi-circular Arbiter England symbol, resembled a smiley face. Denis Cornell, who tested the first Fuzz Faces before they were shipped to retailers, recalls: “He [Ivor Arbiter, Editor's note] used the bottom of a microphone stand to fit the circuit board in, and that is how the round shape came about.”

The circuit was very simple: the Fuzz Face consisted of two transistors, three capacitors and four resistors, plus two potentiometers for gain and volume. It was essentially a Schmitt Trigger, which transformed sine waves into square waves. The pedal was a DPDT switch (double pole/double throw), what today we would call true-bypass pedals.

Ivor was an amateur drummer and ran three shops in West London, including End Drum City Shop on Shaftesbury Avenue and Sound City, which specialised in guitars and amplifiers and was located on Rupert Street. He was also known for having sold, in the early 60s, the Ludwig Black Oyster Pearl drum kit to Ringo Starr, on which he had ‘hastily’ drawn the Beatles logo with the dropped ‘T’, which later went down in history. In 1966 he founded Arbiter-Western.

The shape of the Fuzz Face, which was completely innovative compared to the fuzz boxes currently on the market, was inspired by the base of a microphone stand and, with its two Fuzz and volume knobs, the switch and the semi-circular Arbiter England symbol, resembled a smiley face. Denis Cornell, who tested the first Fuzz Faces before they were shipped to retailers, recalls: “He [Ivor Arbiter, Editor's note] used the bottom of a microphone stand to fit the circuit board in, and that is how the round shape came about.”

The circuit was very simple: the Fuzz Face consisted of two transistors, three capacitors and four resistors, plus two potentiometers for gain and volume. It was essentially a Schmitt Trigger, which transformed sine waves into square waves. The pedal was a DPDT switch (double pole/double throw), what today we would call true-bypass pedals.

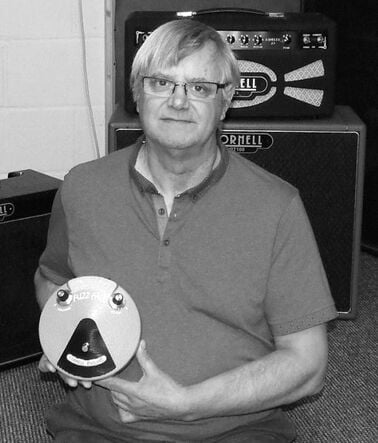

Denis Cornell

Denis Cornell

However, the Fuzz Face was a pretty unstable pedal and it was very difficult to find two that sounded the same. In fact, it was sensitive to temperature, especially when equipped with the NKT75 germanium transistors, to the point that Denis remembers the tests being a nightmare: “At first, testing these units was a nightmare - each unit having different output levels, I seemed to be forever changing transistors to find some kind of common ground. Characteristics of the transistors meant that normal testing by voltage signal and oscilloscope did not pick up the variations in performance. In fact, I hated the job and dreaded when a production run was requested”. Denis soon added a ‘guitar test’ to the test procedure. In fact, this was the only way to find good units: “I soon discovered a technique for knowing what was good. For example, striking a note and listening to the decay: poor units would die away quickly and lose the tone. Also, playing high notes, due to their less high output - the high notes were diminished and would decay faster. Finding a good one was a dream, and the guitar would sustain forever.”

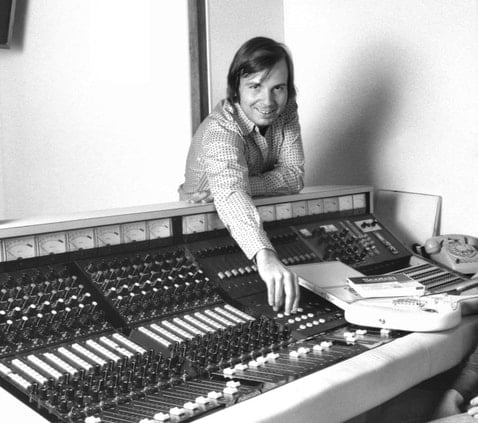

Roger Mayer, Hendrix's historic technician

Roger Mayer, Hendrix's historic technician

Jimi Hendrix used the Fuzz Face a lot live, mainly because it was cheap: it only cost £6, whereas the Maestro cost £30. The drawback was that you had to try many before you found a satisfactory one, as Roger Mayer, Hendrix's historic technician and inventor of the Octavia, recalls: “You might buy 20 pedals to find a really good one, but then it wasn’t stable at all temperatures. [...] Well, Jimi would buy half a dozen of these pedals, find one that sounded great, and then we’d mark it, right? One day it would work and another day it wouldn’t work so well in a different environment. Jimi would say, ‘What’s going on?’ and I’d say, ‘Well, it’s got to be temperature, Jimi.’ [...] In the early days, the control process wasn’t as perfect as it is today. So consequently, there was quite a bit of a spread in the manufacturing. Especially with germanium, it was not quite as tightly controlled as silicon.”

For Roger, however, there was another problem. Being a cheap pedal, the transistors, although of the same type, were all different and were often not well matched: “The crucial transistors could also vary a lot, especially in the amount of gain they produced. So, you never had two early Fuzz Faces that sounded the same. [...] The circuit was so crude and so interdependent that if one transistor was a bit higher-gain than the next stage, you couldn’t use it. You had to get a balanced pair for the thing to sound right.” So Roger would take the Fuzz Faces apart and mix and match the components until he found the right combinations.

But that wasn't the only secret to the sound of Jimi Hendrix's albums. For studio recordings, Roger varied the voltage, used buffers and preamps to adjust the distortion, and the sound we tried so hard to achieve wasn’t replicable with a single pedal: “In the studio, we’d have some other circuits to put in front of the Fuzz Face to drive the unit differently. Of course, in the studio you can vary the voltage you’re running the Fuzz Face on, so we had much more control. I’d put different buffers with different equalization in front of them to drive the actual Fuzz Face from a low-impedance source rather than the high impedance of the guitar. Then we’d add the distortion after that with pre-EQ. Then we could also fuzz the device with post-EQ. You’re not going to get the tone that Jimi Hendrix got on a record with one simple device – that’s not going to happen, mate!”

Roger remembers how, during Hendrix's performances, many Fuzz Faces were lost or stolen. Fortunately, it was a cheap pedal: “Jimi Hendrix had 15 or 20 of them and he used to lose three or four a week! Working with Jimi, straight away within two months I developed my own new fuzz boxes for Jimi that were superior in every way to a Fuzz Face. They weren’t as cheap to make. You couldn’t go and buy 20 of them down the road for £6 each. So, the boxes I made for Jimi, he didn’t want to lose, so we only took out commercial ones on the gigs. Then we didn’t worry if they were stolen. We had 15 or 20 of them and we used to lose three or four a week!”

For Roger, however, there was another problem. Being a cheap pedal, the transistors, although of the same type, were all different and were often not well matched: “The crucial transistors could also vary a lot, especially in the amount of gain they produced. So, you never had two early Fuzz Faces that sounded the same. [...] The circuit was so crude and so interdependent that if one transistor was a bit higher-gain than the next stage, you couldn’t use it. You had to get a balanced pair for the thing to sound right.” So Roger would take the Fuzz Faces apart and mix and match the components until he found the right combinations.

But that wasn't the only secret to the sound of Jimi Hendrix's albums. For studio recordings, Roger varied the voltage, used buffers and preamps to adjust the distortion, and the sound we tried so hard to achieve wasn’t replicable with a single pedal: “In the studio, we’d have some other circuits to put in front of the Fuzz Face to drive the unit differently. Of course, in the studio you can vary the voltage you’re running the Fuzz Face on, so we had much more control. I’d put different buffers with different equalization in front of them to drive the actual Fuzz Face from a low-impedance source rather than the high impedance of the guitar. Then we’d add the distortion after that with pre-EQ. Then we could also fuzz the device with post-EQ. You’re not going to get the tone that Jimi Hendrix got on a record with one simple device – that’s not going to happen, mate!”

Roger remembers how, during Hendrix's performances, many Fuzz Faces were lost or stolen. Fortunately, it was a cheap pedal: “Jimi Hendrix had 15 or 20 of them and he used to lose three or four a week! Working with Jimi, straight away within two months I developed my own new fuzz boxes for Jimi that were superior in every way to a Fuzz Face. They weren’t as cheap to make. You couldn’t go and buy 20 of them down the road for £6 each. So, the boxes I made for Jimi, he didn’t want to lose, so we only took out commercial ones on the gigs. Then we didn’t worry if they were stolen. We had 15 or 20 of them and we used to lose three or four a week!”

Germanium or silicon?

A pair of NKT275s (Joby Sessions - Future)

A pair of NKT275s (Joby Sessions - Future)

One of the most discussed topics among fuzz lovers concerns the eternal dilemma regarding the transistor: germanium or silicon? The first transistors were germanium transistors, used between 1966 and 1968. It wasn’t until later that silicon came into the picture, as Roger Mayer reiterates:

“They were still germanium-only at the beginning of 1967, but I reckon that by about mid-'67 they were on to silicon; by Axis: Bold As Love they were silicon.” Actually this contrasts a bit with what was stated by Tom Huges, the author of Analog Man's Guide to Vintage Effects, who claims that only since Band of Gypsies Hendrix used silicon transistors: “Early Hendrix, that was a germanium Fuzz Face, right up to Are You Experienced?. When he got to the Band of Gypsies, that was silicon.”

It is believed that the first transistor used for the Fuzz Face was the NKT275 germanium transistor by Newmarket. However, Denis Cornell explains that the early Fuzz Face, prior to the NKT75, used another germanium transistor, the AC128: “They all worked in a very similar way and all did the job, but they did give a slightly different tone. I think the ‘Arbiter-England’ one didn’t use the NKT275 germanium transistor; in those days we used the AC128.” This transistor was very popular in Europe at the time and didn't cost much. The SF363E was less common.

“They were still germanium-only at the beginning of 1967, but I reckon that by about mid-'67 they were on to silicon; by Axis: Bold As Love they were silicon.” Actually this contrasts a bit with what was stated by Tom Huges, the author of Analog Man's Guide to Vintage Effects, who claims that only since Band of Gypsies Hendrix used silicon transistors: “Early Hendrix, that was a germanium Fuzz Face, right up to Are You Experienced?. When he got to the Band of Gypsies, that was silicon.”

It is believed that the first transistor used for the Fuzz Face was the NKT275 germanium transistor by Newmarket. However, Denis Cornell explains that the early Fuzz Face, prior to the NKT75, used another germanium transistor, the AC128: “They all worked in a very similar way and all did the job, but they did give a slightly different tone. I think the ‘Arbiter-England’ one didn’t use the NKT275 germanium transistor; in those days we used the AC128.” This transistor was very popular in Europe at the time and didn't cost much. The SF363E was less common.

When silicon transistors appeared, which were easier to obtain and therefore even cheaper, and whose performance as a semiconductor was superior, the Arbiter began to use them instead of germanium transistors. BC108C, BC183L, BC130 and BC209C were more commonly used. Silicon allowed for greater distortion, but more importantly, it was not as susceptible to temperature variations. On the other hand, germanium gave a warmer sound and was appreciated by guitarists because it allowed them to clean the sound of the guitar by simply rolling the volume knob back. However, one of the main shortcomings of the silicon Fuzz Face was that it acted as a radio receiver, as Roger Mayer mentioned: “Arbiter had taken no precautions at all in the design against radio. The silicon had much higher gain and frequencies than the germanium ones. This caused the actual device to become a radio receiver. When you connected the Fuzz Face to a guitar cable, the cable acted like a bloody antenna!”

Dallas

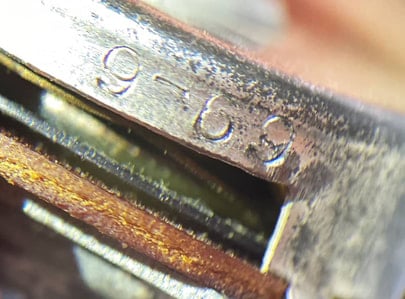

Pot dated "9-69"

Pot dated "9-69"

The Fuzz Face also underwent a number of cosmetic changes, including both the colour and lettering of the ‘smile’.

Early Fuzz Faces were painted with red, light grey or dark grey Hammerite paint, while the Fuzz Face logo and the letters ‘IN’, ‘OUT’, ‘FUZZ’ and ‘VOLUME’ with white or black paint. The inscription ‘ARBITER - ENGLAND’, present on the ‘smile’ of the first copies, was replaced around 1968, by ‘DALLAS - ARBITER - ENGLAND’, after the Arbiter-Western, which had financial problems, merged with Dallas Musical Ltd., forming the new Dallas Arbiter. During this period, the logo changed and, in 1970, the painted letters were replaced by decals. Both models had potentiometers dated October 1966 or August 1968. The bottom surface of the first pedals, thin and shiny, housed the battery compartment (very basic). In the following models, the bottom surface was made thicker and opaquer, and the battery compartment was placed next to the rest of the circuit.

The smile writing changed for the third time to ‘DALLAS MUSIC INDUSTRIES LTD.’ and to ‘CBS/ARBITER LTD.’ after Ivor Arbiter left Dallas in 1974, which became Dallas Musical Industries Ltd.., and Ivor formed the joint venture CBS/Arbiter, thus becoming the official Fender CBS distributor in the UK. Some people think that these two new inscriptions correspond to a production transfer to the United States, but, when you open up a Fuzz Face of the time, it’s clear that they were still being made in England. Around 1969, the first light blue Fuzz Face appeared and between '71 and '72, the dark blue one.

The final batches of Fuzz Face were made in 1975, although it seems that in 1976 a reissue was made, albeit not particularly successfully.

Early Fuzz Faces were painted with red, light grey or dark grey Hammerite paint, while the Fuzz Face logo and the letters ‘IN’, ‘OUT’, ‘FUZZ’ and ‘VOLUME’ with white or black paint. The inscription ‘ARBITER - ENGLAND’, present on the ‘smile’ of the first copies, was replaced around 1968, by ‘DALLAS - ARBITER - ENGLAND’, after the Arbiter-Western, which had financial problems, merged with Dallas Musical Ltd., forming the new Dallas Arbiter. During this period, the logo changed and, in 1970, the painted letters were replaced by decals. Both models had potentiometers dated October 1966 or August 1968. The bottom surface of the first pedals, thin and shiny, housed the battery compartment (very basic). In the following models, the bottom surface was made thicker and opaquer, and the battery compartment was placed next to the rest of the circuit.

The smile writing changed for the third time to ‘DALLAS MUSIC INDUSTRIES LTD.’ and to ‘CBS/ARBITER LTD.’ after Ivor Arbiter left Dallas in 1974, which became Dallas Musical Industries Ltd.., and Ivor formed the joint venture CBS/Arbiter, thus becoming the official Fender CBS distributor in the UK. Some people think that these two new inscriptions correspond to a production transfer to the United States, but, when you open up a Fuzz Face of the time, it’s clear that they were still being made in England. Around 1969, the first light blue Fuzz Face appeared and between '71 and '72, the dark blue one.

The final batches of Fuzz Face were made in 1975, although it seems that in 1976 a reissue was made, albeit not particularly successfully.

The reissues

Dave Fox, 1988

Dave Fox, 1988

In the second half of the 1980s, Crest Audio of New Jersey proposed a reissue of the Fuzz Face based on the BC109C silicon transistor. Crest Audio was a company founded by Jean-Pierre Prideaux, dedicated to the production of amplifiers and racks, which Dallas Musical Instruments bought in the late 1970s.

Dave Fox, who had been working at Crest Audio since 1984, became interested in the old Fuzz Faces and proposed the reissue to John Lee, President of Crest: “I thought it would be cool to start making them again. I went to the President and owner of Crest, a wonderful English man named John Lee, and presented the idea. He liked it. So I start to put the wheels in motion for the new Fuzz Face reissue. [...] I got lots of input from different guitarists and effects collectors all over the country and in England. I was able to borrow some vintage FFs from people. Other people sent me transistors to try out.”

At first, Dave built prototypes with germanium transistors. However, just as with the originals, he ran into some problems and switched to silicon: “I made a bunch of prototypes. I wanted to use the PNP germanium circuit, if possible. I ran into problems. I just couldn't get them to sound good. They sounded dull and lacked sustain. Most of the vintage samples sounded good one day and crappy another day. I didn't know what to make of it. I built up some NPN silicon prototypes and found that they were kind of noisy and very bright. But they had sustain and fire to their sound. I figured I had to go with the NPN version because customers would probably be disappointed with the wimpy tone of the PNP germanium version. Important note back then, the vintage guitar effects market wasn't what it is today. The FF was barely considered vintage at the time. It was just old.”

At the May 1987 NAMM show in Chicago, Dave Fox discovered that Dunlop Manufacturing Inc. was making their own fuzz, the Jimi Hendrix Fuzz. Dave put Jim Dunlop and John Lee in touch and they came to an agreement whereby Dunlop would manufacture the Fuzz Face with the permission of Dallas Musical Instruments. The deal made sense for Dave Fox, as Dunlop was in the guitar accessory business and Crest was in the audio business. Ivor Arbiter would distribute the reissue in the UK.

Between 1986 and 1990, about 2000 copies of Dave Fox's reissue were sold. The first reissues were grey, but then red and blue were made (although there are two yellow and one green copy in Dave's possession), which had the words ‘DALLAS - ARBITER - ENGLAND’ or ‘DALLAS MUSIC INDUSTRIES’ printed on a sticker attached to the pedal.

Dave Fox, who had been working at Crest Audio since 1984, became interested in the old Fuzz Faces and proposed the reissue to John Lee, President of Crest: “I thought it would be cool to start making them again. I went to the President and owner of Crest, a wonderful English man named John Lee, and presented the idea. He liked it. So I start to put the wheels in motion for the new Fuzz Face reissue. [...] I got lots of input from different guitarists and effects collectors all over the country and in England. I was able to borrow some vintage FFs from people. Other people sent me transistors to try out.”

At first, Dave built prototypes with germanium transistors. However, just as with the originals, he ran into some problems and switched to silicon: “I made a bunch of prototypes. I wanted to use the PNP germanium circuit, if possible. I ran into problems. I just couldn't get them to sound good. They sounded dull and lacked sustain. Most of the vintage samples sounded good one day and crappy another day. I didn't know what to make of it. I built up some NPN silicon prototypes and found that they were kind of noisy and very bright. But they had sustain and fire to their sound. I figured I had to go with the NPN version because customers would probably be disappointed with the wimpy tone of the PNP germanium version. Important note back then, the vintage guitar effects market wasn't what it is today. The FF was barely considered vintage at the time. It was just old.”

At the May 1987 NAMM show in Chicago, Dave Fox discovered that Dunlop Manufacturing Inc. was making their own fuzz, the Jimi Hendrix Fuzz. Dave put Jim Dunlop and John Lee in touch and they came to an agreement whereby Dunlop would manufacture the Fuzz Face with the permission of Dallas Musical Instruments. The deal made sense for Dave Fox, as Dunlop was in the guitar accessory business and Crest was in the audio business. Ivor Arbiter would distribute the reissue in the UK.

Between 1986 and 1990, about 2000 copies of Dave Fox's reissue were sold. The first reissues were grey, but then red and blue were made (although there are two yellow and one green copy in Dave's possession), which had the words ‘DALLAS - ARBITER - ENGLAND’ or ‘DALLAS MUSIC INDUSTRIES’ printed on a sticker attached to the pedal.

In 1993, Dunlop bought the Dallas Arbiter and Fuzz Face brands and over the years put many other versions on the market, starting with the red Fuzz Face. Dunlop's early silicon Fuzz Faces didn't sound good and were soon replaced by germanium ones. However, the types used were different, although apparently all were unethically ‘relabelled’ as NKT75.

In 1997, Ivor Arbiter also released a reissue of his pedal similar to the original. This was distributed by Tom Lanik’s brand North Star Audio, with a pair of NKT275 transistors at its core. The ad read: “In an attempt to recapture the pre-Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face sound, Ivor Arbiter recently reissued his original mid-’60s Fuzz Face. From the mic-stand casting to the smile that reads ‘Arbiter/England’ to the PNP Germanium transistors – Arbiter’s reissue is the closest-sounding/looking pedal to the real deal. After all, it’s made by the same company that started the Fuzz Face craze of the ’60s. Re-creating the pedal meant including Denis Cornell, one of the original engineers, and locating original components.”

This reissue was handmade in England and, like the originals, each pedal is different and had the same flaws as the early Fuzz Face. The grey chassis featured the same painted lettering as the original Fuzz Faces and the same controls as the originals, but numbered.

This reissue was handmade in England and, like the originals, each pedal is different and had the same flaws as the early Fuzz Face. The grey chassis featured the same painted lettering as the original Fuzz Faces and the same controls as the originals, but numbered.

After Ivor Arbiter's death in 2005, Denis Cornell marketed his own replica of the Fuzz Face, featuring the words ‘Cornell:England’. However, since Dunlop owned the rights, Cornell was forced to change both the shape and the name of his fuzz to The First Fuzz.

What will become of the Fuzz Face in the future? As long as guitarists still love rock music and the music of the 60s and 70s, the passion for the smiley pedal won't die. Its distinctive sound marked an era, and it's impossible to imagine a world without fuzz.

Antonio Calvosa