Ivor Arbiter

Ivor Arbiter

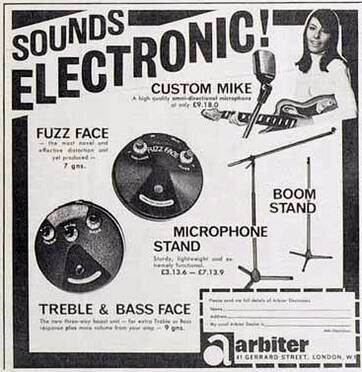

"Fuzz Face is the new fuzz box from Arbiter giving the ultimate in controlled effects", recitava la pubblicità del nuovo Fuzz Face, presentato in Inghilterra da Ivor Arbiter nell'autunno del 1966.

Ivor era un batterista amatoriale e gestiva tre negozi a London’s West, tra cui l'End Drum City Shop, Shaftesbury Avenue, e il Sound City, specializzato in chitarre ed amplificatori, a Rupert Street. Era anche conosciuto per aver venduto, nei primi anni '60, la batteria Black Oyster Pearl Ludwig a Ringo Starr, su cui aveva disegnato "frettolosamente" il logo dei Beatles con la "T" allungata, poi entrata nella storia. Nel 1966 fondò l'Arbiter-Western.

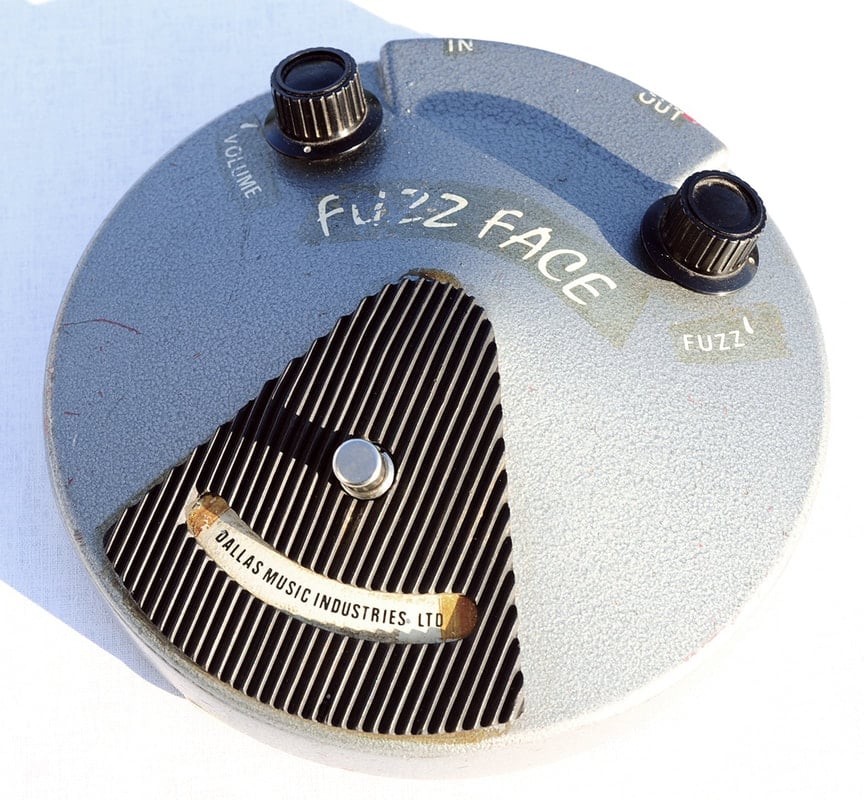

La forma del Fuzz Face, del tutto innovativa rispetto ai fuzz-box venduti fino a quel momento, era ispirata alla base dello stand del microfono e, con le due manopole Fuzz e Volume, l'interruttore e il simbolo semi-circolare "Arbiter England", ricordava un viso sorridente. Denis Cornell, che testava i primi Fuzz Face prima che fossero spediti ai rivenditori, ricorda: «He [Ivor Arbiter, N.d.R.] used the bottom of a microphone stand to fit the circuit board in, and that is how the round shape came about».

Il circuito era molto semplice: il Fuzz Face era costituito da due transistor, tre condensatori e quattro resistenze, oltre a due potenziometri per il gain e per il volume. Era essenzialmente un Trigger di Schmitt, che trasformava le onde sinusoidali in onde quadre. Il pulsante era un DPDT-switch (double pole/double throw), quello che oggi chiameremmo "true bypass".

Ivor era un batterista amatoriale e gestiva tre negozi a London’s West, tra cui l'End Drum City Shop, Shaftesbury Avenue, e il Sound City, specializzato in chitarre ed amplificatori, a Rupert Street. Era anche conosciuto per aver venduto, nei primi anni '60, la batteria Black Oyster Pearl Ludwig a Ringo Starr, su cui aveva disegnato "frettolosamente" il logo dei Beatles con la "T" allungata, poi entrata nella storia. Nel 1966 fondò l'Arbiter-Western.

La forma del Fuzz Face, del tutto innovativa rispetto ai fuzz-box venduti fino a quel momento, era ispirata alla base dello stand del microfono e, con le due manopole Fuzz e Volume, l'interruttore e il simbolo semi-circolare "Arbiter England", ricordava un viso sorridente. Denis Cornell, che testava i primi Fuzz Face prima che fossero spediti ai rivenditori, ricorda: «He [Ivor Arbiter, N.d.R.] used the bottom of a microphone stand to fit the circuit board in, and that is how the round shape came about».

Il circuito era molto semplice: il Fuzz Face era costituito da due transistor, tre condensatori e quattro resistenze, oltre a due potenziometri per il gain e per il volume. Era essenzialmente un Trigger di Schmitt, che trasformava le onde sinusoidali in onde quadre. Il pulsante era un DPDT-switch (double pole/double throw), quello che oggi chiameremmo "true bypass".

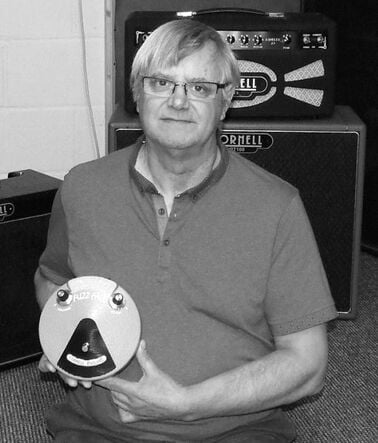

Denis Cornell

Denis Cornell

Tuttavia il Fuzz Face era un pedale piuttosto instabile ed era molto difficile trovane due che suonassero allo stesso modo. Era, infatti, molto sensibile alle temperature, soprattutto se montava i transistor al germanio NKT75, tanto che Denis ricorda i test come un incubo: «At first, testing these units was a nightmare - each unit having different output levels, I seemed to be forever changing transistors to find some kind of common ground. Characteristics of the transistors meant that normal testing by voltage signal and oscilloscope did not pick up the variations in performance. In fact, I hated the job and dreaded when a production run was requested». Per semplificarsi il lavoro, Denis racconta che Iniziò testare i pedali con una chitarra: se il suono si affievoliva subito, non era un pedale riuscito bene, ma quando si trovava di fronte ad un esemplare funzionante «the guitar would sustain forever».

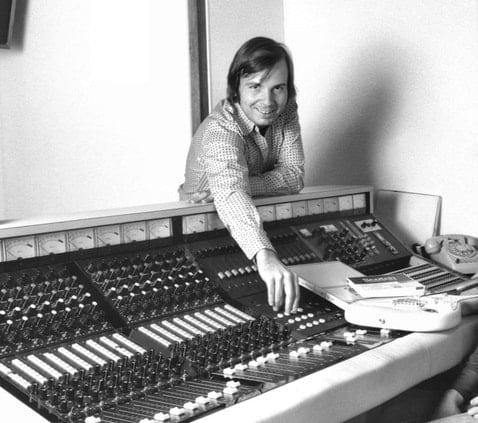

Roger Mayer, il celebre tecnico di Hendrix.

Roger Mayer, il celebre tecnico di Hendrix.

Jimi Hendrix utilizzò molto il Fuzz Face dal vivo, soprattutto perché era economico: costava solo £6, mentre il Mestro costava £30. Il lato negativo era che bisognava prenderne molti prima di trovarne uno soddisfacente, come ricorda Roger Mayer, storico tecnico di Hendrix, inventore dell'Octavia: «You might buy 20 pedals to find a really good one, but then it wasn’t stable at all temperatures. [...] Well, Jimi would buy half a dozen of these pedals, find one that sounded great, and then we’d mark it, right? One day it would work and another day it wouldn’t work so well in a different environment. Jimi would say, ‘What’s going on?’ and I’d say, ‘Well, it’s got to be temperature, Jimi.’ [...] In the early days, the control process wasn’t as perfect as it is today. So consequently, there was quite a bit of a spread in the manufacturing. Especially with germanium, it was not quite as tightly controlled as silicon».

Tuttavia, per Roger, il problema era anche un altro. Essendo un pedale economico, i transistor, anche se dello stesso tipo, erano tutti diversi tra loro e spesso non erano accoppiati bene: «The crucial transistors could also vary a lot, especially in the amount of gain they produced. So, you never had two early Fuzz Faces that sounded the same [...] The circuit was so crude and so interdependent that if one transistor was a bit higher-gain than the next stage, you couldn’t use it. You had to get a balanced pair for the thing to sound right». Per questo Roger smontava i Fuzz Face e mischiava i componenti fino a trovare le giuste combinazioni.

Non solo, il segreto del suono degli album di Jimi Hendrix era anche un altro. Per le registrazioni in studio Roger variava il voltaggio, usava buffer e pre-amplificatori per modificare la distorsione, e il suono che tanto cerchiamo di emulare, non è replicabile con un solo pedale: «In the studio, we’d have some other circuits to put in front of the Fuzz Face to drive the unit differently. Of course, in the studio you can vary the voltage you’re running the Fuzz Face on, so we had much more control. I’d put different buffers with different equalization in front of them to drive the actual Fuzz Face from a low-impedance source rather than the high impedance of the guitar. Then we’d add the distortion after that with pre-EQ. Then we could also fuzz the device with post-EQ. You’re not going to get the tone that Jimi Hendrix got on a record with one simple device – that’s not going to happen, mate»!

Roger ricorda come, nel corso delle esibizioni di Hendrix, molti Fuzz Face erano persi o rubati, ma per fortuna era un pedale poco costoso: «Jimi Hendrix had 15 or 20 of them and he used to lose three or four a week! Working with Jimi, straight away within two months I developed my own new fuzz boxes for Jimi that were superior in every way to a Fuzz Face. They weren’t as cheap to make. You couldn’t go and buy 20 of them down the road for £6 each. So, the boxes I made for Jimi, he didn’t want to lose, so we only took out commercial ones on the gigs. Then we didn’t worry if they were stolen. We had 15 or 20 of them and we used to lose three or four a week»!

Tuttavia, per Roger, il problema era anche un altro. Essendo un pedale economico, i transistor, anche se dello stesso tipo, erano tutti diversi tra loro e spesso non erano accoppiati bene: «The crucial transistors could also vary a lot, especially in the amount of gain they produced. So, you never had two early Fuzz Faces that sounded the same [...] The circuit was so crude and so interdependent that if one transistor was a bit higher-gain than the next stage, you couldn’t use it. You had to get a balanced pair for the thing to sound right». Per questo Roger smontava i Fuzz Face e mischiava i componenti fino a trovare le giuste combinazioni.

Non solo, il segreto del suono degli album di Jimi Hendrix era anche un altro. Per le registrazioni in studio Roger variava il voltaggio, usava buffer e pre-amplificatori per modificare la distorsione, e il suono che tanto cerchiamo di emulare, non è replicabile con un solo pedale: «In the studio, we’d have some other circuits to put in front of the Fuzz Face to drive the unit differently. Of course, in the studio you can vary the voltage you’re running the Fuzz Face on, so we had much more control. I’d put different buffers with different equalization in front of them to drive the actual Fuzz Face from a low-impedance source rather than the high impedance of the guitar. Then we’d add the distortion after that with pre-EQ. Then we could also fuzz the device with post-EQ. You’re not going to get the tone that Jimi Hendrix got on a record with one simple device – that’s not going to happen, mate»!

Roger ricorda come, nel corso delle esibizioni di Hendrix, molti Fuzz Face erano persi o rubati, ma per fortuna era un pedale poco costoso: «Jimi Hendrix had 15 or 20 of them and he used to lose three or four a week! Working with Jimi, straight away within two months I developed my own new fuzz boxes for Jimi that were superior in every way to a Fuzz Face. They weren’t as cheap to make. You couldn’t go and buy 20 of them down the road for £6 each. So, the boxes I made for Jimi, he didn’t want to lose, so we only took out commercial ones on the gigs. Then we didn’t worry if they were stolen. We had 15 or 20 of them and we used to lose three or four a week»!

Germanio o silicio

Una coppia di transistor NKT275 (Joby Sessions - Future)

Una coppia di transistor NKT275 (Joby Sessions - Future)

Uno degli argomenti più trattati tra gli amanti del fuzz riguarda l'eterno dilemma sul transistor: germanio o silicio? I primi transistor erano quelli al germanio, usati tra il 1966 e il 1968, e solo in un secondo momento entrò in scena il silicio, come ribadito da Roger Mayer: «They were still germanium-only at the beginning of 1967, but I reckon that by about mid-'67 they were on to silicon; by Axis: Bold As Love they were silicon». In realtà questo contrasta un po' da quanto affermato da Tom Huges, l'autore di Analog Man's Guide to Vintage Effects, che sostiene che solo da Band of Gypsies Hendrix usò i transistor al silicio: «Early Hendrix, that was a germanium Fuzz Face, right up to Are You Experienced?. When he got to the Band of Gypsies, that was silicon».

È opinione comune considerare che il primo transistor usato sul Fuzz Face fosse quello al germanio NKT275 della Newmarket. Tuttavia Denis Cornell spiega che i primi Fuzz Face, prima dell'NKT75, montavano un altro transistor al germanio, l'AC128: «They all worked in a very similar way and all did the job, but they did give a slightly different tone. I think the ‘Arbiter-England’ one didn’t use the NKT275 germanium transistor; in those days we used the AC128». Questo transistor era molto diffuso in Europa in quel periodo e non costava molto. Più raro era invece quello SF363E.

È opinione comune considerare che il primo transistor usato sul Fuzz Face fosse quello al germanio NKT275 della Newmarket. Tuttavia Denis Cornell spiega che i primi Fuzz Face, prima dell'NKT75, montavano un altro transistor al germanio, l'AC128: «They all worked in a very similar way and all did the job, but they did give a slightly different tone. I think the ‘Arbiter-England’ one didn’t use the NKT275 germanium transistor; in those days we used the AC128». Questo transistor era molto diffuso in Europa in quel periodo e non costava molto. Più raro era invece quello SF363E.

Quando uscirono i transistor al silicio, più facilmente reperibili e quindi ancora più economici, le cui prestazioni come semiconduttore erano superiori, l'Arbiter iniziò ad impiagarli al posto di quelli al germanio. BC108C, BC183L, BC130 e BC209C furono quelli più usati. Il silicio permetteva di raggiungere una distorsione maggiore, ma soprattutto non era soggetto come il germanio alle variazioni di temperatura. D'altra parte, il germanio era più caldo ed era molto apprezzato dai chitarristi perché permetteva di pulire molto il suono della chitarra solo agendo sulla manopola del volume. Tuttavia un grande difetto dei Fuzz Face al silicio era che si comportavano come dei ricevitori radio, come ricordato da Roger Mayer: «Arbiter had taken no precautions at all in the design against radio. The silicon had much higher gain and frequencies than the germanium ones. This caused the actual device to become a radio receiver. When you connected the Fuzz Face to a guitar cable, the cable acted like a bloody antenna»!

La Dallas

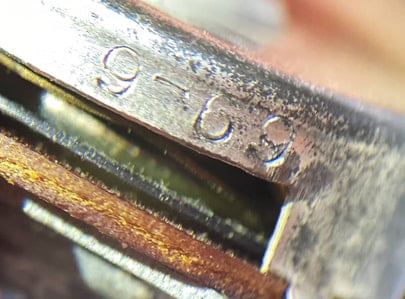

La data del potenziometro "9-69"

La data del potenziometro "9-69"

I Fuzz Face andarono incontro anche a numerose variazioni estetiche, che riguardavano sia il colore, sia le scritte sul "sorriso".

I primi Fuzz Face erano dipinti con vernice Hammerite rossa, grigio chiaro o grigio scuro, mentre il logo "Fuzz Face" e le scritte "IN", "OUT", "FUZZ" e "VOLUME" potevano essere dipinti con vernice bianca o nera. La scritta "ARBITER • ENGLAND", presente sul "sorriso" dei primi esemplari, venne sostituita, nel 1968 circa, da quella "DALLAS – ARBITER • ENGLAND", dopo che l'Arbiter-Western, che aveva problemi finanziari, si fuse con la che la Dallas Musical Ltd., formando la nuova Dallas Arbiter di cui John Lee era il presidente e Ivor Arbiter il Vice Presidente. In questo periodo il logo cambiò e nel 1970 le scritte verniciate furono sostituite con delle decal. Entrambi i modelli avevano i potenziometri datati Ottobre 1966 o Agosto 1968. La superficie inferiore dei primi pedali, sottile e lucida, ospitava il vano batteria (molto rudimentale, a dire il vero); nei modelli successivi divenne più spessa e opaca, e il vano batteria venne affiancato al resto del circuito.

La scritta sul sorriso cambiò una terza volta in "DALLAS MUSIC INDUSTRIES LTD." e in "CBS/ARBITER LTD.", dopo che, nel 1974, Ivor Arbiter lasciò la Dallas, che diventò Dallas Musical Industries Ltd., per costituire la joint-venture CBS/Arbiter, con cui diventò il distributore ufficiale per la Fender CBS nel Regno Unito. Qualcuno pensa che queste due nuove scritte corrispondano ad uno spostamento della produzione negli Stati Uniti, ma, aprendo i Fuzz Face dell'epoca, si capisce facilmente che erano ancora made in England. Intorno al 1969 apparvero i primi Fuzz Face di colore azzurro e tra il '71 e il '72 quello blu.

La produzione del Fuzz Face terminò, infine, nel 1975, anche se sembra che nel 1976 venne fatta una reissue che non ebbe molto successo.

I primi Fuzz Face erano dipinti con vernice Hammerite rossa, grigio chiaro o grigio scuro, mentre il logo "Fuzz Face" e le scritte "IN", "OUT", "FUZZ" e "VOLUME" potevano essere dipinti con vernice bianca o nera. La scritta "ARBITER • ENGLAND", presente sul "sorriso" dei primi esemplari, venne sostituita, nel 1968 circa, da quella "DALLAS – ARBITER • ENGLAND", dopo che l'Arbiter-Western, che aveva problemi finanziari, si fuse con la che la Dallas Musical Ltd., formando la nuova Dallas Arbiter di cui John Lee era il presidente e Ivor Arbiter il Vice Presidente. In questo periodo il logo cambiò e nel 1970 le scritte verniciate furono sostituite con delle decal. Entrambi i modelli avevano i potenziometri datati Ottobre 1966 o Agosto 1968. La superficie inferiore dei primi pedali, sottile e lucida, ospitava il vano batteria (molto rudimentale, a dire il vero); nei modelli successivi divenne più spessa e opaca, e il vano batteria venne affiancato al resto del circuito.

La scritta sul sorriso cambiò una terza volta in "DALLAS MUSIC INDUSTRIES LTD." e in "CBS/ARBITER LTD.", dopo che, nel 1974, Ivor Arbiter lasciò la Dallas, che diventò Dallas Musical Industries Ltd., per costituire la joint-venture CBS/Arbiter, con cui diventò il distributore ufficiale per la Fender CBS nel Regno Unito. Qualcuno pensa che queste due nuove scritte corrispondano ad uno spostamento della produzione negli Stati Uniti, ma, aprendo i Fuzz Face dell'epoca, si capisce facilmente che erano ancora made in England. Intorno al 1969 apparvero i primi Fuzz Face di colore azzurro e tra il '71 e il '72 quello blu.

La produzione del Fuzz Face terminò, infine, nel 1975, anche se sembra che nel 1976 venne fatta una reissue che non ebbe molto successo.

Le reissue

Dave Fox nel 1988

Dave Fox nel 1988

Nella seconda metà degli anni '80 la Crest Audio del New Jersey propose una riedizione del Fuzz Face, basata sul transistor al silicio BC109C. La Crest Audio era un'azienda fondata da Jean-Pierre Prideaux e impegnata nella produzioni di amplificatori e rack, che la Dallas Musical Instruments acquistò alla fine degli anni '70.

Dave Fox, che lavorava alla Crest Audio dal 1984, iniziò ad interessarsi ai vecchi Fuzz Face e propose a John Lee l'idea di una loro reissue: «I thought it would be cool to start making them again. I went to the President and owner of Crest, a wonderful English man named John Lee, and presented the idea. He liked it. So I start to put the wheels in motion for the new Fuzz Face reissue. [...] I got lots of input from different guitarists and effects collectors all over the country and in England. I was able to borrow some vintage FFs from people. Other people sent me transistors to try out».

Inizialmente Dave costruì dei prototipi con transistor al germanio, ma, come gli originali, avevano molti problemi e preferì usare quelli al silicio: «I made a bunch of prototypes. I wanted to use the PNP germanium circuit, if possible. I ran into problems. I just couldn't get them to sound good. They sounded dull and lacked sustain. Most of the vintage samples sounded good one day and crappy another day. I didnt know what to make of it. I built up some NPN silicon prototypes and found that they were kind of noisy and very bright. But they had sustain and fire to their sound. I figured I had to go with the NPN version because customers would probably be disappointed with the wimpy tone of the PNP germanium version. Important note back then, the vintage guitar effects market wasn't what it is today. The FF was barely considered vintage at the time. It was just old».

Al NAMM show di Chicago di maggio 1987, Dave Fox scoprì che anche la Dunlop Manufacturing Inc. produceva un proprio fuzz, il Jimi Hendrix Fuzz. Dave mise in contatto Jim Dunlop e John Lee, che trovarono un accordo, secondo il quale la Dunlop avrebbe fabbricato i Fuzz Face con il permesso della Dallas Musical Instruments. L'accordo aveva senso per Dave Fox, poiché la Dunlop era impegnata nel ramo degli accessori per chitarra, mentre la Crest nel ramo audio. Anche Ivor Arbiter entrò nell'accordo distribuendo la reissue nel Regno Unito.

Tra il 1986 e il 1990 furono venduti circa 2000 esemplari della reissue di Dave Fox, inizialmente solo grigi, ma poi anche rossi e blu (anche se esistono due esemplari gialli ed uno verde in possesso di Dave), che avevano la scritta "DALLAS – ARBITER • ENGLAND" o "DALLAS MUSIC INDUSTRIES" stampata su uno sticker attaccato al pedale.

Dave Fox, che lavorava alla Crest Audio dal 1984, iniziò ad interessarsi ai vecchi Fuzz Face e propose a John Lee l'idea di una loro reissue: «I thought it would be cool to start making them again. I went to the President and owner of Crest, a wonderful English man named John Lee, and presented the idea. He liked it. So I start to put the wheels in motion for the new Fuzz Face reissue. [...] I got lots of input from different guitarists and effects collectors all over the country and in England. I was able to borrow some vintage FFs from people. Other people sent me transistors to try out».

Inizialmente Dave costruì dei prototipi con transistor al germanio, ma, come gli originali, avevano molti problemi e preferì usare quelli al silicio: «I made a bunch of prototypes. I wanted to use the PNP germanium circuit, if possible. I ran into problems. I just couldn't get them to sound good. They sounded dull and lacked sustain. Most of the vintage samples sounded good one day and crappy another day. I didnt know what to make of it. I built up some NPN silicon prototypes and found that they were kind of noisy and very bright. But they had sustain and fire to their sound. I figured I had to go with the NPN version because customers would probably be disappointed with the wimpy tone of the PNP germanium version. Important note back then, the vintage guitar effects market wasn't what it is today. The FF was barely considered vintage at the time. It was just old».

Al NAMM show di Chicago di maggio 1987, Dave Fox scoprì che anche la Dunlop Manufacturing Inc. produceva un proprio fuzz, il Jimi Hendrix Fuzz. Dave mise in contatto Jim Dunlop e John Lee, che trovarono un accordo, secondo il quale la Dunlop avrebbe fabbricato i Fuzz Face con il permesso della Dallas Musical Instruments. L'accordo aveva senso per Dave Fox, poiché la Dunlop era impegnata nel ramo degli accessori per chitarra, mentre la Crest nel ramo audio. Anche Ivor Arbiter entrò nell'accordo distribuendo la reissue nel Regno Unito.

Tra il 1986 e il 1990 furono venduti circa 2000 esemplari della reissue di Dave Fox, inizialmente solo grigi, ma poi anche rossi e blu (anche se esistono due esemplari gialli ed uno verde in possesso di Dave), che avevano la scritta "DALLAS – ARBITER • ENGLAND" o "DALLAS MUSIC INDUSTRIES" stampata su uno sticker attaccato al pedale.

Nel 1993 la Dunlop acquistò i marchi Dallas Arbiter e Fuzz Face e, negli anni, mise in commercio molte altre versioni, iniziando da Fuzz Face rossi. I primi Fuzz Face della Dunlop, al silicio, non suonavano bene e furono presto sostituiti da quelli germanio. Tuttavia i tipi utilizzati erano diversi, ma sembra che furono tutti "rebrandizzati", in modo poco etico, con la dicitura NKT75.

Anche Ivor Arbiter mise in commercio, nel 1997, una riedizione del suo pedale più vicina all'originale, distribuita dalla North Star Audio di Tom Lanik, nel cui cuore c'era una coppia di transistor NKT275. La pubblicità recitava: "In an attempt to recapture the pre-Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face sound, Ivor Arbiter recently reissued his original mid-’60s Fuzz Face. From the mic-stand casting to the smile that reads “Arbiter/England” to the PNP Germanium transistors – Arbiter’s reissue is the closest-sounding/looking pedal to the real deal. After all, it’s made by the same company that started the Fuzz Face craze of the ’60s. Re-creating the pedal meant including Denis Cornell, one of the original engineers, and locating original components". Questa reissue era costruita a mano in Inghilterra, e, come gli originali, ogni pedale era diverso dall'altro ed aveva gli stessi difetti dei primi Fuzz Face. Sullo chassis grigio spiccavano le scritte dipinte come sui Fuzz Face originali e manopole uguali alle originali, ma numerate.

Dopo la morte di Ivor Arbiter nel 2005, Denis Cornell commercializzò una propria replica del Fuzz Face, sul cui sorriso spiccava la scritta "Cornell:England". Tuttavia, siccome la Dunlop deteneva i diritti fu costretto a cambiare sia la forma del suo fuzz, sia il nome, che cambiò in The First Fuzz.

Cosa sarà del Fuzz Face nel futuro? Finché i chitarristi continueranno ad amare il rock e la musica degli anni '60 e '70, la passione verso il pedale che sorride non finirà. Il suo suono così caratteristico ha segnato un'epoca, ed è impossibile immaginare un modo senza fuzz. Lunga vita al Fuzz Face!

Antonio Calvosa