|

Magnetic poles of the pickups of the Telecaster are made of AlNiCo, an iron alloy composed also of Aluminum, Nickel and Cobalt hence the acronym al-ni-co. It could also include copper, titanium or niobium. Pole pieces were beveled on the top end and pressed into the fiber from the bottom, which left an uneven surface look on the fibers. Some early production poles could even be partially covered with fiber residue!

According to their chemical composition and magnetic properties, alnico magnets are traditionally classified using numbers from II to IX. It's important to bear in mind that Alnico V magnets used by Leo Fender in the '50s and '60s were different from Alnico V magnets used today, because their primary constituents and impurities proportions were different from that of the most recently produced magnets. Moreover, it is possible to find some Alnico III poles on bridge pickup during the Blackguard era. |

Obviously, composition of the magnets is not the only critical factor which influences the pickup tone. Coil wires, winding methods, encapsulation of the coil and pole dimensions have a subtle influence over the sound.

THE SINGLE COIL BRIDGE PICKUP

|

The bridge pickup, fitted into the bridge, is often considered the heart of the unique Telecaster/Esquire twangy tone. Leo slanted the pickup to give stronger bass tones, thus avoiding the medium frequencies that gave the instrument the grave sound which he called ʺfluff”.

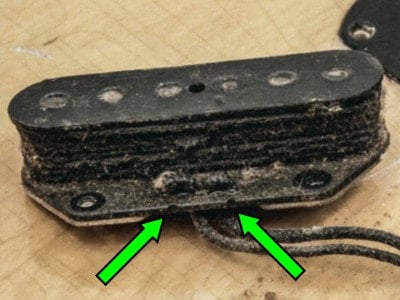

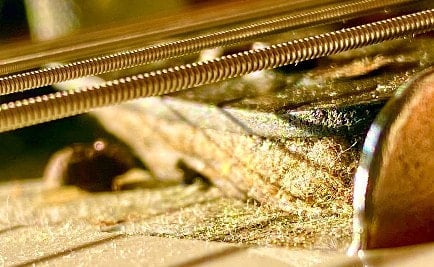

This pickup consists of a bobbin made of two stamped vulcanized fiber plates held together by six non-adjustable alnico pole pieces and surrounded by a coil. Some bridge pickup bottom fibers included small notches to wrap around the coil to the eyelets. |

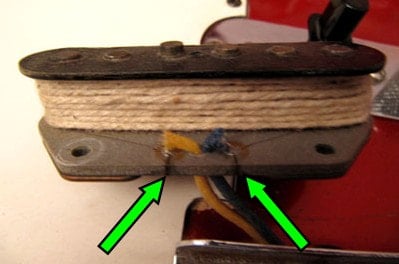

Initially, the coil was protected by black tape, but around 1951 Fender gradually switched over to black (at first) and then white cotton string. Since the early '70s, the color of the cotton string has reverted to black.

The poles of the first lead pickups were “flat”; however, some Telecaster guitars came out of the factory with an unbalanced sound and with the low E too strong, owing to a still somewhat inconsistent production. Leo fixed this, from late 1955, by staggering the height of the magnetic poles with a raised D and G pole pieces. This said, although the sound was now more balanced, it was also sharper.

Flat poles bridge pickup reappeared only in 1981 on the '52 Vintage Reissue and was later reinstated on the American Standard.

The poles of the first lead pickups were “flat”; however, some Telecaster guitars came out of the factory with an unbalanced sound and with the low E too strong, owing to a still somewhat inconsistent production. Leo fixed this, from late 1955, by staggering the height of the magnetic poles with a raised D and G pole pieces. This said, although the sound was now more balanced, it was also sharper.

Flat poles bridge pickup reappeared only in 1981 on the '52 Vintage Reissue and was later reinstated on the American Standard.

|

Small notches used to wrap around the coil to the eyelets, 1952 Telecaster, Photo from Our Vintage Soul Volume II by Flavio Camorani and Michela Taioli

|

Bridge pickups were not wound to an exacting number of turns, but to deliver a certain output on a volt-meter with a 20% tolerance, which explains why there are variations in the measurements of vintage units. Furthermore, initially Leo Fender didn't use 42 AWG wire windings, but slightly skinnier 43 gauge with a higher DC resistance, and some of the very first bridge pickups featured more than 10000 turns of wire and a few of them originally boasted a DC resistance well above 9k Ohms.

Towards the end of 1950, however, Fender switched to 42 gauge wire. The thicker wire allowed a lesser numbers of turns, thus reducing labor cost. New units featured on average 9200 turns and delivered anything between 7k and 7.8k Ohms.

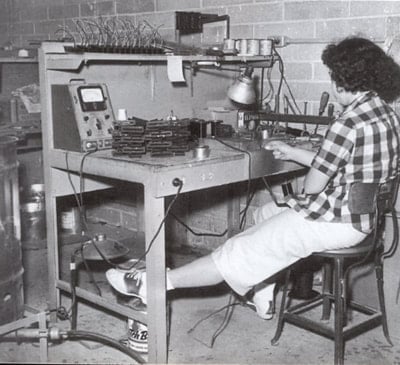

Until 1964 Fender pickups were wound with hand-guiding machines, which turned the bobbin, while a worker would guide the wire onto the turning bobbin. The readings for the number of turns came through a belt-driven worm gear counter, which was a fairly inconsistent piece of machinery.

The exact number of turns and the tension in winding, which could stretch wire and affect its diameter and length, could vary from pickup to pickup and influenced the tone.

In 1965, with the CBS takeover, Fender gradually replaced the old-style hand-guiding machines with new auto-winders and conversion ratios brought about some confusion. Newer coils were more consistent with neatly parallel winding, but as rule they were not wrapped as tightly as the older ones, because wrapping tight on an automatic winder tended to break wire. Therefore, older pickups usually had a slightly higher output, whilst newer ones had a little more top frequency response.

Towards the end of 1950, however, Fender switched to 42 gauge wire. The thicker wire allowed a lesser numbers of turns, thus reducing labor cost. New units featured on average 9200 turns and delivered anything between 7k and 7.8k Ohms.

Until 1964 Fender pickups were wound with hand-guiding machines, which turned the bobbin, while a worker would guide the wire onto the turning bobbin. The readings for the number of turns came through a belt-driven worm gear counter, which was a fairly inconsistent piece of machinery.

The exact number of turns and the tension in winding, which could stretch wire and affect its diameter and length, could vary from pickup to pickup and influenced the tone.

In 1965, with the CBS takeover, Fender gradually replaced the old-style hand-guiding machines with new auto-winders and conversion ratios brought about some confusion. Newer coils were more consistent with neatly parallel winding, but as rule they were not wrapped as tightly as the older ones, because wrapping tight on an automatic winder tended to break wire. Therefore, older pickups usually had a slightly higher output, whilst newer ones had a little more top frequency response.

|

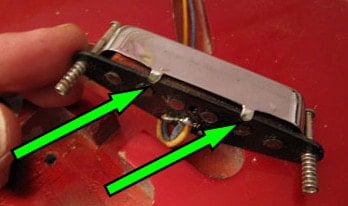

Unlike other Fender single coil pickups, the Esquire/Telecaster bridge unit featured an elevator plate under the bobbin. It was made of zinc-plated cold rolled steel until early 1951 when it became copper-plated, which is easier to solder. The purpose of the elevator plate was to create a ground loop through the bridge via the three screws which fixed the bridge pickup to the plate. It was die-stamped in-house using Race & Olmsted machinery. Snake head and the second prototypes were devoid of this plate.

|

THE SINGLE COIL NECK PICKUP

|

The neck pickup bobbin was smaller than that of the bridge unit and the coil has fewer windings. It was screwed onto the body rather than being suspended from the pickguard. With the aim of protect the coil from electronic interference, thus avoiding unwanted noise, it was covered by a metal shell. The pole pieces of the early units were flat, whilst they were slightly protruding at both ends on more recent ones.

The neck pickup kept the same gauge wire (i.e. 43AWG) of the early bridge units, but, unlike them, it never changed to 42 gauge wire. |

Those made in the '50s usually featured about 8000 turns of wire and delivered anything between 7.3k and 8.1k Ohms.

As happened to the bridge pickup, the introduction of auto-winders in 1965 and conversion ratios brought about some confusion, and the number of turns changed back and forth in the late '60s before settling down to an average 7800 turns, which gave a resistance of 6.5k to 7.3k Ohms.

After 1981, Fender switched back to old resistance value (between 7.3k and 8.1k Ohms).

As happened to the bridge pickup, the introduction of auto-winders in 1965 and conversion ratios brought about some confusion, and the number of turns changed back and forth in the late '60s before settling down to an average 7800 turns, which gave a resistance of 6.5k to 7.3k Ohms.

After 1981, Fender switched back to old resistance value (between 7.3k and 8.1k Ohms).

BLACK AND GREY BOTTOM

|

Originally, the top and bottom plates were made of forbon, a black vulcanized fiber, hence the name black bottom pickups.

Their windings had an intense copper color due to the formvar (poly vinyl formal varnish) insulation, a polyvinyl resin. Prior to winding the coil, the bobbin was dipped in clear lacquer to insulate the magnets from the coil and eliminating a possible source of microphonic noises. After the coil was wound, the whole assembly was also immersed in hot paraffin black wax to saturate the coil, a process known as wax potting. |

For this reason, the white cotton string that protect the bridge pickup today is often darkened with dust and dirt. Both bridge and neck pickup were lacquered, but only the bridge unit was wax potted.

Since March 1964, Fender started to gradually replace the black bottom pickups with the new grey bottom units, characterized by a grey bottom plate, at first light grey and slightly darker after 1968. Grey bottom units finally replaced the black bottom pickups at the end of 1967. However, in the '70s, a few black bottom single coil pickups were used by Fender, because, in order to run out of stock, undated pickups with black fiber bottom plates were made.

The windings of the new pickups were burgundy color due to the new insulating coating, plain enamel.

Unlike the black bottom units, gray bottoms were not always wax potted, but they were lacquer potted. This process had to be done during the winding as the lacquer did not penetrate deeply into the coils. In the '70s, the lacquer potting was sometimes done too late (or it was not done at all), and the result was the production of microphonic pickups. For a long time it was not possible to understand the nature of this problem, which was solved only in late 1981 thanks to Dan Smith, who resumed the wax-dipping procedure. Since black bottom pickups were not dipped in paraffin wax, the white cotton string that protect the bridge pickup is much cleaner on the late ‘60s black bottom pickups than on grey bottom pickups.

Since March 1964, Fender started to gradually replace the black bottom pickups with the new grey bottom units, characterized by a grey bottom plate, at first light grey and slightly darker after 1968. Grey bottom units finally replaced the black bottom pickups at the end of 1967. However, in the '70s, a few black bottom single coil pickups were used by Fender, because, in order to run out of stock, undated pickups with black fiber bottom plates were made.

The windings of the new pickups were burgundy color due to the new insulating coating, plain enamel.

Unlike the black bottom units, gray bottoms were not always wax potted, but they were lacquer potted. This process had to be done during the winding as the lacquer did not penetrate deeply into the coils. In the '70s, the lacquer potting was sometimes done too late (or it was not done at all), and the result was the production of microphonic pickups. For a long time it was not possible to understand the nature of this problem, which was solved only in late 1981 thanks to Dan Smith, who resumed the wax-dipping procedure. Since black bottom pickups were not dipped in paraffin wax, the white cotton string that protect the bridge pickup is much cleaner on the late ‘60s black bottom pickups than on grey bottom pickups.

The '70S Humbucking Pickups

|

The Fender Wide Range Humbucking Pickup was the first Fender humbucker. This pickup featured twelve threaded magnetic poles made of CuNiFe, an alloy based on copper, nickel and iron. Once the metal cover was soldered, only six pole pieces, split in two offset rows, came out of the cover and could be adjusted in height: those of E, A and D of the coil closest to the neck and those of G, B and high E of the coil closest to the bridge. The other poles were upside down and were hidden by the cover. This allowed for a stronger magnetic field compared to that obtained by Seth with Gibson PAFs, characterized by a single Alnico magnet under the coils.

|

The sound produced was brighter and the resistance of about 10kOhms guaranteed a higher output.

PICKUPS DATES

In early 1964 Fender started to date the bottom plate of most of its pickup's bobbins. However, Telecaster's neck pickups were not usually dated because of their too narrow bottom with protruding magnets. Hence, only the bridge pickup was likely to feature any date, but it is not easy to see it because of the shielding plate.

During the '60s and '70s, three different types of markings were thus successively applied:

During the '60s and '70s, three different types of markings were thus successively applied:

- Black bottom pickups featured a rubber-stamped date with yellow ink or a white pastel pencil (e.g. “APR 11 64”)

- The very first light grey bottom pickups, introduced in 1965, featured the same rubber-stamped date with yellow ink used on black bottom pickups, but they were soon dated by hand with a with a pencil or a black ink marking pen (e.g. “12-6-65”). The initials of the worker who had wound them were sometimes present.

- Dark grey bottom pickups, introduced in ca. 1969, featured a 3 to 6-digit code, rubber-stamped in black or red, of which the last or the last two digits indicated the year.

- '70s Fender Wide Range Humbucking pickups sported a similar rubber-stamped code in black or yellow on the metal bottom plate.

It's should be noted that the code was stamped when the pickup was finished and stored, and therefore there was often a gap of a couple of weeks or months with the assembling date!