|

Leo wasn’t a guitarist, but he was a great listener, and he took advantage of the proposals of the guitarists he attended - Rex Robert Gallion and Bill Carson over all.

Rex Gallion was a country-western guitarist, who was specifically involved in the evolution of the “Custom Contour” body. He is often quoted as having asked Fender: “Why not get away from a body that is always digging into your ribs?” |

|

Bill Carson was a famous country guitarist who had played in the Eddy Kirk Band, for Hank Thompson and for Billy Gray. He met Leo at the end of 1951 and was hired by Fender at the end of 1957 as salesman. Leo used to let Bill test the prototypes of the new guitar. Indeed, Bill was Leo’s “favorite guinea pig for the Strat.” He brought several of the Telecaster’s perceived shortcomings to Leo’s attention.

Bill needed a more comfortable body, which should “fit like shirt.” He said many times that he had the idea of the contoured body first, even though Leo Fender in his recollection always claimed that Rex Gallion suggested contours for the Stratocaster’s body before Bill Carson did. “Before he [Bill Carson] came out, we’d been soliciting information from every musician we could find,” Leo said. “The body design itself was a sort of a product in conjunction with Rex Gallion. Rex wanted me to make the relief on the backside of the guitar so it would not dig him so much in the rib cage and they wanted a little carving away of the corner on top. […] So, we designed the thing according to the way Rex started. We would feel good to him.” |

|

But, to be accurate, when Freddie Tavares went to work part-time with Leo in March 1953, no drawings had been made on the guitar.

Freddie was a steel guitarist born in Hawaii in 1913 who often played in Los Angeles — the opening slide in the Looney Tunes cartoon theme is his. He met Leo in 1953 through Noel Boggs, another steel guitarist promoter of Fender products, and he began working as his assistant, giving up the career as musician. Freddie drew the shape of the body and neck according to Leo's exacting directions. He drew different renditions of the Stratocaster on a drafting table in the Santa Fe/Pomona Avenue factory, using the Precision Bass as a model, making many false starts and erasure corrections. Much work had likely been done on the components before Freddie arrived, but Freddie helped Leo take several works-in-progress and blend them into a refined, cohesive whole. |

|

Leo worked hard on new single-coil pickups, because he thought the Telecaster’s worst problems was due to the pickups’ uneven response between strings and the microphonic feedback which afflicted some of them.

Fender tested a wide variety of pickup designs. Fender’s 1953 inventory sheets listed 117 Stratocaster elevator plates, which were discarded because Leo discovered that elevator plates and metal covers contributed to the Telecaster’s feedback. Leo decided to use staggered pole pieces to obtain a more balanced response from each string, thus differentiating them from the early Telecaster flat-pole pickups. With the old-style heavy-gauge sets, the plain B string had a strong signal, so Leo made its pole the shortest, whilst the D pole was the tallest. George Fullerton said they gave Bill Carson a lot of the pickups, to take on gigs and try. Oddly enough, Leo Fender explained he decided to use three pickups because he had plenty of 3-position switches in stock for steel guitars and Telecasters! Freddie Tavares remembered that Leo said: “Let’s put three pickups. Two is good, but three will kill ‘em!” |

|

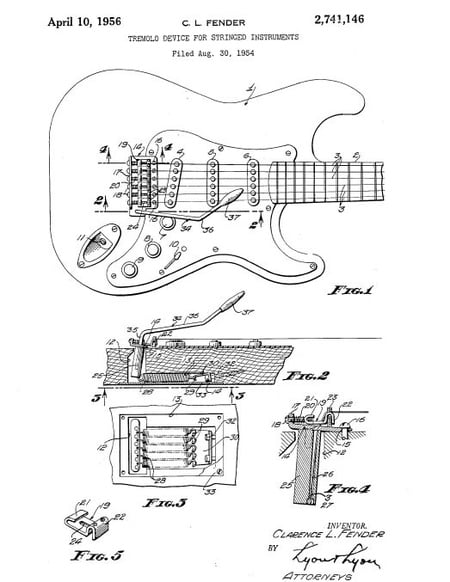

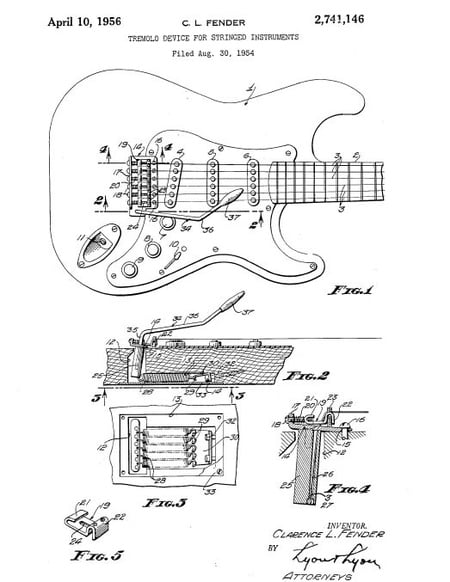

According to Tavares, the Stratocaster would have been unveiled long before if it wasn't for its tremolo, which was developed in more than six months — one year according to Carson and Fullerton. Actually, the term ‘tremolo’ was not correct because this unit was a vibrato. In fact, tremolo is a modulation effect that creates a change in volume, while vibrato is a mechanical device used to temporarily change the pitch of the strings. The source of this error can probably be found because Leo was inspired by the “Apparatus for producing tremolo effects” designed by his friend Doc Kauffman, whose patent was applied for in 1928 and officially granted to on January 5, 1932.

Leo resolutely wanted this type of bridge to compete with all the tremolo units, as the Bigsby’s system, that were gaining ever greater success among the guitarists of the '50s and that most of the time consisted of fixed bridges on which the strings were stretched or loosened. But they all had a big fault: they did not always bring the instrument back to proper tuning. |

|

The guitar was equipped with a black phenolite pickguard, Telecaster-style chrome dome knobs and a top-hat switch tip, and the pickups lacked the covers. The vibrato unit was almost exactly as we know it today, but it had a thicker tremolo arm and the inertia bar was drilled on the back for three springs, not five, hence the vibrato sported only three springs, which were held on with screws anchored into the wood, not with the spring claw. Also, the body back route was only wide enough for three springs. The neck had a dark lacquer finish, the headstock lacked any decal on front and on the back a masking tape stood out. The highly figured ash body was unfinished, typical of Leo’s test guitars. In the neck pocket, Leo Fender's initials were faintly written in pencil.

|

|

The prototype was featured in an article by Willie G. Moseley originally appeared in the April 2008 issue of Vintage Guitar magazine. According to Willie, the guitar was later obtained by Jerry Madderra. He inherited it from his father, Thomas, who brought home a box of guitar parts he acquired from employees of Fender’s plant in 1954. Thomas passed away in 1957 and never detailed the acquisition of the parts of the guitar.

Leo Fender would have no interest in preserving the originality of a test mule, so the guitar may have had components switched around even before that box of parts left the factory. The bridge was primitive, except for the saddles. “I don’t think they’re the ones Leo made,” Madderra said. “They appear to be 1954-production saddles that were put on the earlier bridge; they’re stamped with ‘Patent Pending’ and look like production parts rather than handmade, while the bridge looks handmade or perhaps like a prototype. The bridge plate never had chrome on it. And the inertia bar on the back is drilled for three springs, just like the one in the [Stratocaster prototype] photos taken by Leo Fender.” The switch was a three-way CRL 1452 with four patent numbers. Pickups, pickguard and knobs were replaced. As a child and young man, Madderra didn’t have any interest in playing guitar, but when he did start in the late ’50s, it was on the made-from-parts Strat. |

|

The Stratocaster was officially announced in 1954, in the April issue of the International Musician magazine. At the suggestion of Don Randall, the new guitar was called Stratocaster, continuing the Broadcaster and Telecaster series, with the reference to the space, since the new instrument would have brought the design of the guitars into a new stratosphere. In a letter to dealers, Fender Sales specified that “shipments are expected to begin May 15,” although an early pre-production run started before. The Stratocaster 0100, which was dated 4/54 on the body and 01-54 on the neck, was probably the first in this series. Guitars made until April probably served as salesmen's samples, most were eventually sold, leading to confusion about what constituted the Stratocaster’s first commercial production run. Certain aspects of these early 1954 Stratocasters looked primitive, almost handmade compared with later versions .

|

|

The starting price of the Stratocaster was $249.50 without case, about 10% more than the Gibson Les Paul Gold Top and about 30% less than the Custom. The few models made without tremolo cost $229.50 without case. With $39.95 in addition you could buy the Stratocasters inside the shaped cases built by Baldwin. These cases were called poodle cases due to the fact that whoever carried them seemed to be walking a poodle. At the end of 1954 they were replaced by the more resistant Victoria Luggage tweed cases, which, with different variations in style, were used throughout the golden age of Fender.

|

|

© COPYRIGHT 2014-2024 FUZZFACED.NET BY ANTONIO CALVOSA - TUTTI I DIRITTI RISERVATI

La copia, la riproduzione, la pubblicazione e la redistribuzione dei contenuti, se non autorizzate espressamente dall'autore, sono vietate in qualsiasi modo o forma. |

|

© COPYRIGHT 2014-2024 FUZZFACED.NET BY ANTONIO CALVOSA - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The copying, reproduction, publication and redistribution of the contents, unless expressly authorized by the author, are prohibited in any way or form. |