Lacquers

Until 1967, Fender mainly used very thin coats of nitrocellulose (Duco colors) or acrylic lacquers (Lucite colors). Nitro and acrylic lacquers were widely used in the automotive industry because they were easy to apply and dried fast, looked great and could be polished easily to remove minor scratches.

These paints consisted mainly of three components: the pigment, the binder and the solvent. The pigment, responsible for the color, could be organic or inorganic and was dispersed in binder, which protected it.

They were both dissolved in acetone (hence the name “lacquers”), which was an extremely fast evaporating solvent. When lacquers dried, they formed a thin paint layer which adhered to the surface of body of the guitar.

But nitro lacquers had a problem: when they dried, they lost their elasticity and tended to crack, phenomenon known as checking. Furthermore, some pigments tended to fade when subjected to UV rays, a phenomenon known as fading, whilst the clear coat layer always yellowed, even with minimal UV exposure (“yellowing”). On the contrary, acrylic finishes were more UV resistant than nitrocellulose and were more elastic, which means that they were not affected by the checking problem.

These paints consisted mainly of three components: the pigment, the binder and the solvent. The pigment, responsible for the color, could be organic or inorganic and was dispersed in binder, which protected it.

They were both dissolved in acetone (hence the name “lacquers”), which was an extremely fast evaporating solvent. When lacquers dried, they formed a thin paint layer which adhered to the surface of body of the guitar.

But nitro lacquers had a problem: when they dried, they lost their elasticity and tended to crack, phenomenon known as checking. Furthermore, some pigments tended to fade when subjected to UV rays, a phenomenon known as fading, whilst the clear coat layer always yellowed, even with minimal UV exposure (“yellowing”). On the contrary, acrylic finishes were more UV resistant than nitrocellulose and were more elastic, which means that they were not affected by the checking problem.

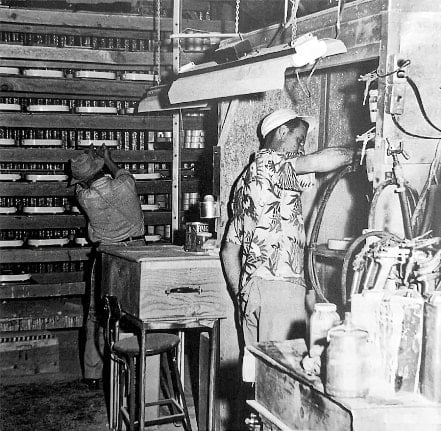

HOW FINISH COATS WERE APPLIED

A Fender body usually features three different types of finishing coats: an under coat, a color coat and a top clear coat.

The clear coat was a transparent nitro layer - never acrylic - usually used on both sunburst and custom color Stratocasters, but above all on the custom metallic colors. Indeed, their inorganic pigments derived from various metallic ores, will oxidize easily if they don't have a protective clear coat over them. Hence, metallic finishes had always to be clear coated, where the pastel colors didn't require it.

The nitrocellulose-based binder in nitrocellulose clear coat yellowed over time when exposed to even moderate sunlight, smog, smoke and sweat, thus significantly chancing the original color of the guitar. Yellowed Olympic White Stratocasters are a classic example of yellowing phenomenon. These guitars are often confused with the Blonde ones, but they can be easily spotted because Blond was a transparent finish, used on ash bodies emphasize its grain patterns.

However, not all Stratocasters featured a clear coat, especially if it was necessary to speed up production to satisfy all orders. Since ’62-’63, when requests had begun to increase significantly, this habit became more frequent. Guitars without the clear coat can be distinguished because they don't yellow, as vintage Olympic White Stratocasters that are still white today can demonstrate.

The under coat was used to the finishing process to make it more efficient and saving money. Since the end of the '50s, Fender had often used a transparent sealer to fill the pores creating a seal that prevents following coats from soaking into the wood, thus saving color paint and money. Sealer was particularly useful with the ash, which is a very porous wood.

At the beginning, on the Stratocasters of the ’54 (as on the Blackguard Telecasters) a mixture that contained nitro and sand was used. Guitars thus treated showed a three-dimensional aspect when they were observed in the light.

Later, Fender had used other insulating materials, like the Homoclad, or, since 1962, the Fullerplast, which “encapsulated” the bodies just like the polyester paints used in the CBS period did. The Fullerplast, which takes its name from that of its inventor, Fuller O'Brien, was transparent, it dried very quickly, could be applied in a very thin way and was absorbed by the alder in depth, although this wood was not famous for its porosity. It was sprayed on the body immediately after the yellow paint was applied and did not interact with paint solvents. This prevented the colors applied later from being absorbed by the wood and allowed to have a thinner layer of paint, thus saving time and material.

During the '60, Fender discontinuously used a white primer undercoat to make custom color adhere better and applied in less quantity, ensuring money savings. Of course, the financial disadvantage to using a primer undercoat was it took more time, because it implied another step where they had to let the body dry. So, when the production schedule allowed and they had the time to use a primer undercoat, they did. Depending on the color, if they didn't have the time or were backordered, they avoided using the primer.

Fender also used Sunburst, alone or under a white primer, as an undercoat to custom colors. Stripping an existing Sunburst bad finish to apply another was just too much work. So, shooting a new custom color directly over a rejected body allowed to save time and money. Other times it was the customer who explicitly requested, at the time of purchase and with a 5% surcharge, that the instrument be repainted with a custom color. This option could be requested both in the US and in Europe at the official distributors that received the original paints directly from the Fender factory. These factory or dealers refin are recognizable thanks to the large identification numbers imprinted on the body or on the neck (in the US) or to small stamps under the neck plate or in the neck pocket (in Europe) which allowed recognition and the return to the owner of the instrument.

The clear coat was a transparent nitro layer - never acrylic - usually used on both sunburst and custom color Stratocasters, but above all on the custom metallic colors. Indeed, their inorganic pigments derived from various metallic ores, will oxidize easily if they don't have a protective clear coat over them. Hence, metallic finishes had always to be clear coated, where the pastel colors didn't require it.

The nitrocellulose-based binder in nitrocellulose clear coat yellowed over time when exposed to even moderate sunlight, smog, smoke and sweat, thus significantly chancing the original color of the guitar. Yellowed Olympic White Stratocasters are a classic example of yellowing phenomenon. These guitars are often confused with the Blonde ones, but they can be easily spotted because Blond was a transparent finish, used on ash bodies emphasize its grain patterns.

However, not all Stratocasters featured a clear coat, especially if it was necessary to speed up production to satisfy all orders. Since ’62-’63, when requests had begun to increase significantly, this habit became more frequent. Guitars without the clear coat can be distinguished because they don't yellow, as vintage Olympic White Stratocasters that are still white today can demonstrate.

The under coat was used to the finishing process to make it more efficient and saving money. Since the end of the '50s, Fender had often used a transparent sealer to fill the pores creating a seal that prevents following coats from soaking into the wood, thus saving color paint and money. Sealer was particularly useful with the ash, which is a very porous wood.

At the beginning, on the Stratocasters of the ’54 (as on the Blackguard Telecasters) a mixture that contained nitro and sand was used. Guitars thus treated showed a three-dimensional aspect when they were observed in the light.

Later, Fender had used other insulating materials, like the Homoclad, or, since 1962, the Fullerplast, which “encapsulated” the bodies just like the polyester paints used in the CBS period did. The Fullerplast, which takes its name from that of its inventor, Fuller O'Brien, was transparent, it dried very quickly, could be applied in a very thin way and was absorbed by the alder in depth, although this wood was not famous for its porosity. It was sprayed on the body immediately after the yellow paint was applied and did not interact with paint solvents. This prevented the colors applied later from being absorbed by the wood and allowed to have a thinner layer of paint, thus saving time and material.

During the '60, Fender discontinuously used a white primer undercoat to make custom color adhere better and applied in less quantity, ensuring money savings. Of course, the financial disadvantage to using a primer undercoat was it took more time, because it implied another step where they had to let the body dry. So, when the production schedule allowed and they had the time to use a primer undercoat, they did. Depending on the color, if they didn't have the time or were backordered, they avoided using the primer.

Fender also used Sunburst, alone or under a white primer, as an undercoat to custom colors. Stripping an existing Sunburst bad finish to apply another was just too much work. So, shooting a new custom color directly over a rejected body allowed to save time and money. Other times it was the customer who explicitly requested, at the time of purchase and with a 5% surcharge, that the instrument be repainted with a custom color. This option could be requested both in the US and in Europe at the official distributors that received the original paints directly from the Fender factory. These factory or dealers refin are recognizable thanks to the large identification numbers imprinted on the body or on the neck (in the US) or to small stamps under the neck plate or in the neck pocket (in Europe) which allowed recognition and the return to the owner of the instrument.

In 1958, the red paint of the first 3-Color Sunburst Stratocasters was sprayed also on the part of the body covered by the pickguard. This practice was abandoned almost immediately in the same year, both to save paint and to speed up the finishing process, as it would not have been visible. On the contrary, the black paint was sprayed starting directly from the edge or, sometimes, from the part of the body under the pickguard, probably to test the spray gun or to clean the nozzle.

During 1969, Fender started to apply more black paint on the back of the body near the neck plate.

During 1969, Fender started to apply more black paint on the back of the body near the neck plate.

|

All pre-CBS Fender Stratocaster bodies that date from before the end of 1964 have three or four 1/16” nail holes on the front (see also the chapter on the Stratocaster body). Fender used the nails as spacers for the painting/drying process. Before applying the finish, three or four small nails were hammered into the body face. The body was therefore arranged on a turntable called “Lazy Susan” and was painted on the top. Then the body was flipped over onto the nails in order to paint the back and sides of the body. The painted body was left on its nail legs to dry. When the finish was dry, the nails were removed, thus leaving small holes free of paint, called nail holes or clamping holes. However, since the body was rubbed out after the nails were removed, nail holes may have some white or pink rubbing compound junk in them.

|

Since the end of 1964 Fender changed the painting process and the nails were no more used. Thus, clamping holes may help to authenticate pre-CBS bodies and to distinguish them from modern reissues or fakes. The presence of paint (and not of pink rubbing compound) inside nail holes indicates that the guitar has been refinished.

Around the end of 1962, with the purpose of rotating the body in the spray booth for easy spraying and drying operations, Fender started to use a paint stick, a piece of an electrical conduit pipe. It was screwed in the neck pocket in the two bass-side screw holes after the application of yellow and before spraying the other colors. Therefore, the area under the stick in the neck pocket remained yellow, whilst, prior to the paint stick, the neck pocket was completely painted. The other side of the stick was put around a freehand rotating tool so that the body could be turned in all directions during the painting process. It's important to bear in mind that nails were still used for the drying process, but since the end of 1964 they were replaced by a drying tree on which the sticks could be attached, which took up less space.

Since mid-1964 Fender has changed the way the paints were applied. A new opaque, less transparent sunburst, called target burst, in which the colors were not blended perfectly, was the result of the use of a semitransparent white under coat. At the same time, however, this new technique helped to hide the imperfections of the wood grain and the less attractive bodies.

Between the end of ’67 and ’68 Fender again modified the way to paint guitars.

Between the end of ’67 and ’68 Fender again modified the way to paint guitars.

Few less attractive Stratocasters bodies made in 1969, like those usually destinated to solid colors, featured a kind of sunburst dubbed faux burst. The white primer of these guitars was characterized by scratching made with hard brushes to simulate wood grain.

In the mid-1960s the alder pieces that composed the body were sometimes so well matched that the grains seemed to continue from piece to piece, so that it was difficult to recognize the lines of separation of the pieces. These bodies were identified with the writing “no fill”, which served to instruct the paint workers not to apply yellow to emphasize the grain.

In the mid-1960s the alder pieces that composed the body were sometimes so well matched that the grains seemed to continue from piece to piece, so that it was difficult to recognize the lines of separation of the pieces. These bodies were identified with the writing “no fill”, which served to instruct the paint workers not to apply yellow to emphasize the grain.

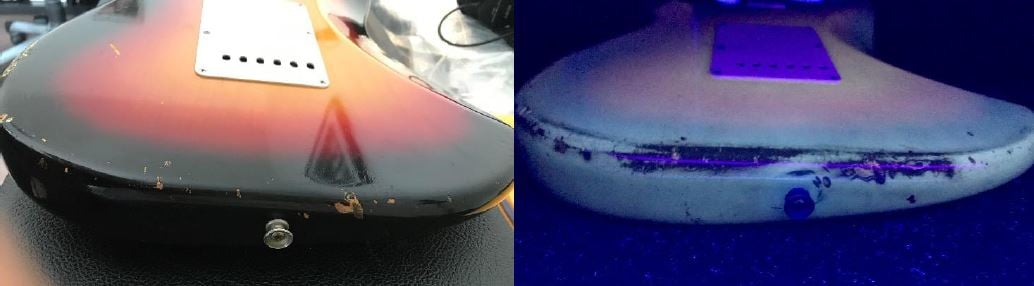

Some pictures related to UV light checks could be nice as well to see the wearings that can not be seen in normal conditions (proof of real vintage Fender)

POLYESTER

Until about 1968, Fender mainly used thin coats of nitrocellulose lacquers on its guitars, although some custom colors were actually done with acrylic paints. However, nitrocellulose lacquers are fairly unstable, harder to deal with and can generate dangerous toxic fumes. After CBS took over Fender, polyester finishes were brought in, primarily because they are better suited to mass production. Polyester was an aliphatic polyurethane consisting of long polyester molecules.

By late 1967, Fender began to replace the clear coat, made so far of many coats of nitro, with only two coats of polyester. However, the color coat was still made up of acrylic or nitro lacquers. The advantage, obviously, was a significant time savings, because polyester dried very quickly. In addition, this new material did not turn yellow over time and was much more resistant than nitro.

However, it should be bear in mind that not all Fender guitars were completely finished with polyester, some colors continued to have the old nitro coating. Moreover, also the front side of the headstock stayed entirely lacquer, even though the rest of the neck was polyester finished, because decals reacted with polyester, and completely nitro necks dated 1967 and 1968 are not uncommon.

In late 1971, thicker coats of polyester, used as clear coat and under coat, soon generated a major change in the look and feel of Fender guitars as the company developed its “Thick Skin” high-gloss finish, whilst finishes used on '50s and '60s instruments went down in history with the nickname “Think Skin”. Indeed, '70s bodies were sprayed with anything like 10-15 coats of polyester!

'70s were years of strong experimentation, during which numerous alternatives and combinations had been tested. For example, the Olympic White kept a nitro clear coat (with a polyester undercoat) until 1977; the sunburst also in this period was made in the same way. In short, there wasn’t a standard rule.

In 1979, Fender was asked by both the Air Quality Management District and the Environmental Protection Agency to modify its spraying installation and to find a less polluting finishing method. Then Fender decided to try water-based finishes, which could be electrostatically sprayed on bodies, but the result was disastrous: the water-based paint was prone to cracking, it just came off in big sheets, and looked like broken eggshells, and consequently Fender was forced to return to polyester finishes.

By late 1967, Fender began to replace the clear coat, made so far of many coats of nitro, with only two coats of polyester. However, the color coat was still made up of acrylic or nitro lacquers. The advantage, obviously, was a significant time savings, because polyester dried very quickly. In addition, this new material did not turn yellow over time and was much more resistant than nitro.

However, it should be bear in mind that not all Fender guitars were completely finished with polyester, some colors continued to have the old nitro coating. Moreover, also the front side of the headstock stayed entirely lacquer, even though the rest of the neck was polyester finished, because decals reacted with polyester, and completely nitro necks dated 1967 and 1968 are not uncommon.

In late 1971, thicker coats of polyester, used as clear coat and under coat, soon generated a major change in the look and feel of Fender guitars as the company developed its “Thick Skin” high-gloss finish, whilst finishes used on '50s and '60s instruments went down in history with the nickname “Think Skin”. Indeed, '70s bodies were sprayed with anything like 10-15 coats of polyester!

'70s were years of strong experimentation, during which numerous alternatives and combinations had been tested. For example, the Olympic White kept a nitro clear coat (with a polyester undercoat) until 1977; the sunburst also in this period was made in the same way. In short, there wasn’t a standard rule.

In 1979, Fender was asked by both the Air Quality Management District and the Environmental Protection Agency to modify its spraying installation and to find a less polluting finishing method. Then Fender decided to try water-based finishes, which could be electrostatically sprayed on bodies, but the result was disastrous: the water-based paint was prone to cracking, it just came off in big sheets, and looked like broken eggshells, and consequently Fender was forced to return to polyester finishes.

Polyurethane

By late 1981, under the Schultz-Smith management, a new type of polyurethane, applied thinner than the previous polyester, began to replace it for the clear coat, in the Standard Stratocaster known as “Smith Strat”. However, polyester was kept as undercoat. Shortly before the close-down of the Fullerton plant Fender started to use it also for the color coat. The new 1987 American Standard Stratocaster exhibited a polyurethane finish, but polyester was still used as undercoat to better adhere the color.