WOOD MATERIAL

|

Esquire prototypes, early samples and pre-production models featured a Oregon Pine (Pseudotsuga Menziesii) body, but, in October 1950, Leo Fender quickly chose to use more eye-catching Northern White Ash (Fraxinus Americana) and Red Ash (Fraxinus Pennsylvanica) bodies that fit well with the semi-transparent blond finish. Bodies were generally made of two pieces (although one or three-piece bodies are known to exist) often meticulously matched to emphasize the grain patterns - even diagonal seams across the entire body were not unusual on early '50s Fender guitars!

Ash is an inconsistent timber. It can sport some striking grain patterns and may appear very light or it can be pretty plain and heavy. Its grain and its weight depend both on where the tree grows and which portion of the tree is used to cut the body. Generally speaking, the more water is absorbed by the tree, the lighter the eventual wood spread. When saturated with water the grain gets wider but, as the water recedes under warmer weather, the wood dries out and becomes much lighter. Usually, the bottom portion of the tree usually absorbs more water, particularly during winter, than the top portion. |

So, swamp ash is not a particular species of ash as often reported, but it is a term generally used by luthiers to describe lightweight wood yielded from ash trees which are usually found in wet or swampy areas, and obtaining light and figured ash is not a question of luck, but a matter of specifications and price when ordering wood.

Since weight was not a prime consideration when procuring ash, you can find Fender Telecaster bodies of variable density. Usually, ash bodies from the '50s were lighter on the average than those from the '60s or '70s. The weight of ash purchased in the mid-60s is probably one of the major reasons behind the Telecaster Thinline.

The pine bodies of the first prototypes were 1.5” thick, whilst many early ash bodies were 1.69”. Finally, in October 1950, Fender started the production of the first 1.75” thick bodies, which became the standard trim on Telecaster-style guitars. The change to a thicker body was due to the need of a deeper control cavity when Leo Fender decided to replace the push/pull switch with the 3-way switch.

Since weight was not a prime consideration when procuring ash, you can find Fender Telecaster bodies of variable density. Usually, ash bodies from the '50s were lighter on the average than those from the '60s or '70s. The weight of ash purchased in the mid-60s is probably one of the major reasons behind the Telecaster Thinline.

The pine bodies of the first prototypes were 1.5” thick, whilst many early ash bodies were 1.69”. Finally, in October 1950, Fender started the production of the first 1.75” thick bodies, which became the standard trim on Telecaster-style guitars. The change to a thicker body was due to the need of a deeper control cavity when Leo Fender decided to replace the push/pull switch with the 3-way switch.

In mid-1956, Fender started using alder for the sunburst Stratocaster and all instruments that were not finished in blond, because it was less porous and therefore easier to paint.

Regular Telecaster and Esquires featured a stock blond finish and retained an ash body. By 1956, though, special colors became available at 5% charge, which means that custom colored Telecasters were produced with an alder body. Although sunburst was not a special finish per se at factory level, it was a true custom color for regular Telecasters and Esquires, and '60s sunburst models were fitted with an alder body, whilst the extremely rare late '50s sunburst Telecaster and Esquires retained an ash body.

In mid-1959, Fender unveiled the new Telecaster Custom, which came in a 3-Color Sunburst bound alder body - but custom colors were available. Until 1972 most Customs were fitted with an alder body.

Regular Telecaster and Esquires featured a stock blond finish and retained an ash body. By 1956, though, special colors became available at 5% charge, which means that custom colored Telecasters were produced with an alder body. Although sunburst was not a special finish per se at factory level, it was a true custom color for regular Telecasters and Esquires, and '60s sunburst models were fitted with an alder body, whilst the extremely rare late '50s sunburst Telecaster and Esquires retained an ash body.

In mid-1959, Fender unveiled the new Telecaster Custom, which came in a 3-Color Sunburst bound alder body - but custom colors were available. Until 1972 most Customs were fitted with an alder body.

In 1963, Fender introduced an optional mahogany body and a reddish finish on the regular Telecaster, available on special order. It was not produced in large quantities and was discontinued after 1965.

The Telecaster Thinline, introduced in 1968, was at first released in only natural ash and mahogany bodies.

However, occasionally Fender used other timbers, such rosewood, used on the Rosewood Telecaster produced over 1969-72, hackberry wood, in lieu of ash on Telecasters in the '70s, zebrawood on a few experimental guitars, American black walnut on the Walnut Elite Telecaster.

The Telecaster Thinline, introduced in 1968, was at first released in only natural ash and mahogany bodies.

However, occasionally Fender used other timbers, such rosewood, used on the Rosewood Telecaster produced over 1969-72, hackberry wood, in lieu of ash on Telecasters in the '70s, zebrawood on a few experimental guitars, American black walnut on the Walnut Elite Telecaster.

OVERALL SHAPE

George Fullerton, Leo Fender's close friend, was a very good woodworker, and it is to him that we owe the original shape of the Telecaster.

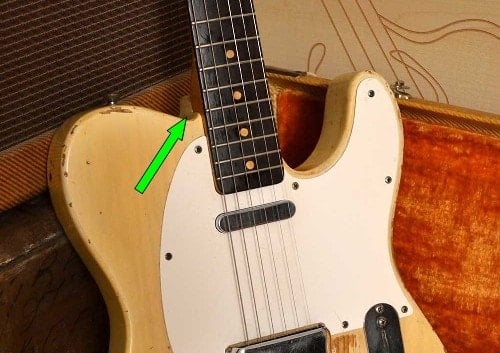

In the '70s the typical notch found on the '50s and '60s bodies was removed from the bass side of the neck pocket.

In the '70s the typical notch found on the '50s and '60s bodies was removed from the bass side of the neck pocket.

'70s and probably a very few late '60 Telecasters had a different carve of the upper shoulder and a slightly different body shape, because Fender started to use the 3/4 diameter inch cutter to make the body instead of the smaller 1/2 cutter needed to make that tiny spot on the bass side.

Furthermore, the upper edge of the body of '50s and '60s Telecasters joints into the neck at the 17th fret after a fairly steep curve, whilst, on most '70s and early '80s guitars, it joins the neck at the 16th fret after a much flatter curve. In mid-1981, the new Standard Telecaster featured again the steeper curve.

Furthermore, the upper edge of the body of '50s and '60s Telecasters joints into the neck at the 17th fret after a fairly steep curve, whilst, on most '70s and early '80s guitars, it joins the neck at the 16th fret after a much flatter curve. In mid-1981, the new Standard Telecaster featured again the steeper curve.

1957 vs 1978 Telecaster body shape. Courtesy of True Vintage Guitar

The neck pocket of the early '50s Telecasters didn't perfectly match the shape of the neck heel. Indeed, the body featured a protruding “lip” below the neck heel because the neck pocket was initially shaped with perpendicular sides, without considering that the neck heel does not form a 90° angle. By approximately 1956, the neck pocket was drilled with a slightly smaller angle to perfectly fit the shape of the neck heel.

ROUTINGS

Initially, Leo Fender didn’t consider a neck pickup and Esquire bodies were not routed for it until the Summer of 1950. Hence, the earliest Esquires featured only two top routing: for the bridge pickup and the controls.

Then, Telecaster-style guitars featured three top routings: for the neck pickup, the bridge pickup and the controls. It’s important to bear in mind that once Leo Fender opted for the dual pickup option, both single and dual pickup guitars shared the same body routings regardless of what model would be final assembled.

The first pre-production non-truss rod dual pickup Esquires, made during the summer of 1950, were devoid of the truss rod channel access route, but featured a drill channel from the neck pocket to neck pickup cavity.

Around mid-February 1951, the factory changed the body routing to reduce the wiring assembly time by avoiding the passing of the neck pickup leads through the bridge pickup cavity. A few earliest Nocasters, dated February 1951, showed a round “donut” hole in the center of the body, under the pickguard, which were performed when the guitars had already been lacquered, to allow a second drill bit to make its way into the control cavity. This change was also important in terms of the customer service, as it would not be necessary to remove the whole bridge assembly in case the neck pickup had to be replaced.

Shortly thereafter, a diagonal route between the neck pickup and the controls cavity was settled on. This design would make it easy to drill a single hole from the neck pickup cavity the to the diagonal channel, whilst a second short passage could be drilled from the bottom of the diagonal channel to the control cavity. This stayed as the standard routing configuration until the summer of 1969, when new machinery and drilling equipment put an end to the need of the diagonal route, which was suppressed. It was later reintroduced on the Vintage reissue '52 Telecaster. Also the very first American Standard Telecasters featured the diagonal route, but, by 1988, they sported a single open channel between the neck pickup and the controls cavity.

It’s important to bear in mind that it’s not uncommon to find hand-made enlargements of the cavities on early guitars after it had been lacquered.

Then, Telecaster-style guitars featured three top routings: for the neck pickup, the bridge pickup and the controls. It’s important to bear in mind that once Leo Fender opted for the dual pickup option, both single and dual pickup guitars shared the same body routings regardless of what model would be final assembled.

The first pre-production non-truss rod dual pickup Esquires, made during the summer of 1950, were devoid of the truss rod channel access route, but featured a drill channel from the neck pocket to neck pickup cavity.

Around mid-February 1951, the factory changed the body routing to reduce the wiring assembly time by avoiding the passing of the neck pickup leads through the bridge pickup cavity. A few earliest Nocasters, dated February 1951, showed a round “donut” hole in the center of the body, under the pickguard, which were performed when the guitars had already been lacquered, to allow a second drill bit to make its way into the control cavity. This change was also important in terms of the customer service, as it would not be necessary to remove the whole bridge assembly in case the neck pickup had to be replaced.

Shortly thereafter, a diagonal route between the neck pickup and the controls cavity was settled on. This design would make it easy to drill a single hole from the neck pickup cavity the to the diagonal channel, whilst a second short passage could be drilled from the bottom of the diagonal channel to the control cavity. This stayed as the standard routing configuration until the summer of 1969, when new machinery and drilling equipment put an end to the need of the diagonal route, which was suppressed. It was later reintroduced on the Vintage reissue '52 Telecaster. Also the very first American Standard Telecasters featured the diagonal route, but, by 1988, they sported a single open channel between the neck pickup and the controls cavity.

It’s important to bear in mind that it’s not uncommon to find hand-made enlargements of the cavities on early guitars after it had been lacquered.

|

In late 1967, Fender manufactured a few “Smuggler's Telecasters”. Fender had a problem finding light weight ash for Tele bodies, so in the spirit of being resourceful and working with what they had, they began exploring ways to make lighter guitars. Removing the pickguard reveals three rather large cavities where part of the ash body was removed. In 1968, Fender engineers decided to pursue more drastic modifications, which led to the creation of the Thinline model.

|

PIN ROUTER’S HOLES

|

From '50s until late '70s, Fender used a pin router and templates to cut guitars body edges and routes. Routing templates had locating pins to secure them onto the underside of the body blanks. When the template was lifted off, small holes were filled with hardwood dowel and then leveled.

Obviously dowels are always in exactly the same place. Usually, they are not easy to spot on a painted body because they were well patched up and camouflaged. However, old nitro finishes were really thin and, observing carefully the body surface, the dowel outlines can be seen through the finish. |

Dowels can be spotted on the back of the Telecaster in two places:

However, Vintage reissue and on some Custom Shop guitars were still made with the old pin router and therefore they still featured dowel holes.

It should be noted that pin router's holes were in completely different positions on the Stratocaster. They also went all the way through the body because Fender's employees had to screw templates onto both sides of the body.

- Between the neck plate and the string ferrules, at a distance of about 3 3/16" from the lower edge of the neck plate.

- Between the string ferrules and the bottom end of the body, at a distance of about 1" from the bottom end of the body.

However, Vintage reissue and on some Custom Shop guitars were still made with the old pin router and therefore they still featured dowel holes.

It should be noted that pin router's holes were in completely different positions on the Stratocaster. They also went all the way through the body because Fender's employees had to screw templates onto both sides of the body.

The body of the Rosewood Telecaster featured one or two maple dowels in the neck pocket and in the bridge pickup cavity to ensure a correct alignment of the body halves sandwiching the thin maple core strip.

NAIL HOLES

|

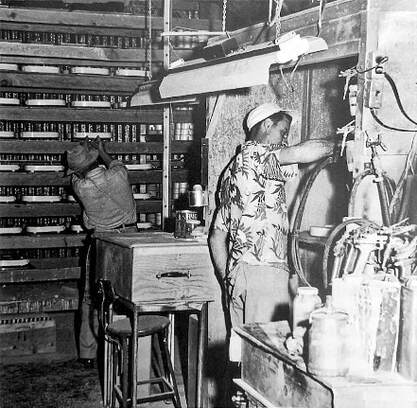

All Telecaster bodies that date from before the autumn of 1964 have three or four 1/16” nail holes on the front. Fender used the nails as spacers for the painting/drying process. Before applying the finish, three or four small nails were hammered into the body face. The body was therefore arranged on a turntable called “Lazy Susan” and was painted on the top. Then the body was flipped over onto the nails in order to paint the back and sides of the body. The painted body was left on its nail legs to dry. When the finish was dry, the nails were removed, thus leaving small holes free of paint, called nail holes or clamping holes. However, since the body was rubbed out after the nails were removed, nail holes may have some white or pink rubbing compound junk in them.

|

Until mid-1959, older Telecaster bodies usually feature nail holes on the front face, respectively located:

- Under the pickguard, between the front pickup and the neck pocket

- Under the control plate, next to the bottom screw hole of the plate

- Under the bridge plate, near the upper holes drilled for the strings and the plate screws

- Under the pickguard, near the extreme pickguard screw hole in the cutaway horn (until late 1958)

In mid-1959, Fender moved the nails to inside the routed cavities and the fourth nail positioned on the cutaway was dropped. New nail holes were respectively located:

- Inside the neck pocket or truss rod adjustment route

- Inside the bridge pickup route

- Inside the wall of the control cavity route

In late 1964 Fender changed the painting process and the nails were no more used.

It should be noted that the placement of Broadcaster nail holes is slightly different than 1951 to 1958 Telecasters.

It should be noted that the placement of Broadcaster nail holes is slightly different than 1951 to 1958 Telecasters.

THE JACK CUP AND STRING FERRULES

|

The standard output jack was a mono jack made by Switchcraft. Esquire, Broadcaster and Telecaster guitars featured a heavy milled jack cup, which was machined and knurled by Edmiston using cold rolled steel.

After late 1952 cups were made of pressed steel and screwed onto a small drilled plate which was anchored to the body’s jack route. Fender Telecaster-style guitars string ferrules were machined by Edmiston from cold rolled steel rods and nickel plated. String ferrule holes were protruding and were not countersunk on prototypes, pre-production and earliest production guitars. These holes were drilled using temporary body templates and were often misaligned. |

Guitars made between mid-1950 and 1966 had countersunk and flush with the body string ferrules.

After 1966, the ferrules are clearly protruding on the back of the body, but after the 1985 buyout Fender reverted to flush ferrules.

After 1966, the ferrules are clearly protruding on the back of the body, but after the 1985 buyout Fender reverted to flush ferrules.

BODY DATES AND MARKINGS

|

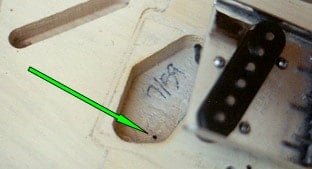

Pre-production guitars bodies were not dated until October 1950, when body dates were first written in the neck pocket of the body of the Telecaster-style guitars. In 1956 the body date was moved to the lead pickup cavity.

These markings were always written on the bare wood, once the cutting was completed, prior to being finished. However, over the years bodies have not been dated quite as consistently as necks and bodies were common dated between late 1950 and 1963 only. Besides, they are mostly visible on guitars with a light finish such as blonde or sunburst, but they usually do not show under an opaque custom color finish. Bodies made from mid-1951 until late 1955 sometimes sported a “D” stamp in the neck pocket. Nobody knows its meaning. George Daimler, a former Fender employee, claimed that it stands for “inspected”. A few collectors supposed “D” stands for “detected”, “done”, “dried” or “checked”. |

- Between 1950 and late 1953, the date is usually penciled in numerals in the neck pocket according to the month/day/year of production. The initials or the first name of the employee who made or checked the body was also present, as “IWAB”, “EM”, “Davis” (which stood for Charlie Davis) and “Eddie” (which probably stood for Eddie Mendoza), “TAD” and “TG” (maybe both for Tadeo Gomez), “Kenny”, “IP” “TK”, “Art”, or “J.S”.

- After late 1953, the day of production, as well as the initials of the employee, was gradually phased out.

- Between 1954 and 1963, the body date simply indicated the month and the year in numerals.

- In 1956, the date was relocated in the lead pickup cavity, right under the bridge plate. Dates may still appear on some 1964 guitars, but they were basically discontinued in late 1963.

- During the '70s and '80s, body date, when present, was written among names inspection dates in the neck pocket either penciled or stamped.

- “INSP” circled stamp

- “FRR” circled stamp (which stood for “Fender/Rogers/Rhodes”) with a numeric code of the WWYD type (since the end of the '70s). “WW” stands for the week, “Y” the year and “D” the day of the week. “0304” indicates therefore the third week of 1980, Thursday.

MASKING TAPE MARKINGS

Guitars manufactured between mid-1951 and 1956 usually featured a date penciled on a piece of masking tape, located in the control cavity. These tape inscriptions were affixed either on the side or on the bottom of the cavity routing and marked the wiring harness were installed into the body. Therefore, they usually were the last date found on a Fender guitar.

Most of these inscriptions were signed with female first names such as Mary, Gloria, Virginia, Barbara or Carolyn.

Most of these inscriptions were signed with female first names such as Mary, Gloria, Virginia, Barbara or Carolyn.

MOUNTING SCREWS

In the early days, Leo Fender bought the screws from readily available stock, and therefore he used many different types of screws on prototypes and pre-production guitars.

All the 1950 Telecaster-style guitars featured slot head screws, including the adjustable truss rod bolt. In 1951, Fender started a gradual transition towards Phillips head screws, but the transition was completed by the end of 1953, because Leo Fender didn’t want to waste anything.

In the course of 1951, the controls plate and the strap buttons changed to Phillips heads. The four screws holding the bridge base plate changed to Phillips head in early 1952, whilst pickguard screws where replaced in late 1952. Until the summer of 1953 slot head screws could be still used for holding the bridge pickup and the selector switch.

All the 1950 Telecaster-style guitars featured slot head screws, including the adjustable truss rod bolt. In 1951, Fender started a gradual transition towards Phillips head screws, but the transition was completed by the end of 1953, because Leo Fender didn’t want to waste anything.

In the course of 1951, the controls plate and the strap buttons changed to Phillips heads. The four screws holding the bridge base plate changed to Phillips head in early 1952, whilst pickguard screws where replaced in late 1952. Until the summer of 1953 slot head screws could be still used for holding the bridge pickup and the selector switch.