LACQUERS

Until 1967 Fender mainly used very thin coats of nitrocellulose (Duco colors) or acrylic lacquers (Lucite colors). Nitro and acrylic lacquers were widely used in the automotive industry because they were easy to apply and dried fast, looked great and could be polished easily to remove minor scratches.

These paints consisted mainly of three components: the pigment, the binder and the solvent. Pigment, responsible for the color, could be organic or inorganic and was dispersed in binder, which protected it.

They were both dissolved in acetone (hence the name "lacquers"), which was an extremely fast evaporating solvent. When lacquers dried, they formed a thin paint layer which adhered to the surface of body of the guitar.

But nitro lacquers had a problem: when they dried, they lost their elasticity and tended to crack, phenomenon known as checking. Furthermore, some pigments tended to fade when subjected to UV rays, a phenomenon known as fading, whilst the clear coat layer always yellowed, even with minimal UV exposure (yellowing). On the contrary, acrylic finishes were more UV resistant than celluloid and were more elastic, which means that they were not affected by the checking problem.

When the '52 reissue project was launched, Freddie Tavares and other Fender engineers reckoned that the paint used in the early '50s Telecasters was actually white with a touch of beige in it. Ageing mostly made it turn to a yellower shade.

These paints consisted mainly of three components: the pigment, the binder and the solvent. Pigment, responsible for the color, could be organic or inorganic and was dispersed in binder, which protected it.

They were both dissolved in acetone (hence the name "lacquers"), which was an extremely fast evaporating solvent. When lacquers dried, they formed a thin paint layer which adhered to the surface of body of the guitar.

But nitro lacquers had a problem: when they dried, they lost their elasticity and tended to crack, phenomenon known as checking. Furthermore, some pigments tended to fade when subjected to UV rays, a phenomenon known as fading, whilst the clear coat layer always yellowed, even with minimal UV exposure (yellowing). On the contrary, acrylic finishes were more UV resistant than celluloid and were more elastic, which means that they were not affected by the checking problem.

When the '52 reissue project was launched, Freddie Tavares and other Fender engineers reckoned that the paint used in the early '50s Telecasters was actually white with a touch of beige in it. Ageing mostly made it turn to a yellower shade.

HOW FINISH COATS WERE APPLIED

A Fender body usually features three different types of finishing coats: an under coat, a color coat and a top clear coat.

The clear coat was a transparent nitro layer - never acrylic - usually used on both sunburst and custom color Telecasters, but above all on the custom metallic colors. Indeed, their inorganic pigments derived from various metallic ores, will oxidize easily if they don't have a protective clear coat over them. Hence, metallic finishes had always to be clear coated, where the pastel colors didn't require it.

The celluloid-based binder in nitrocellulose clear coat yellowed over time when exposed to even moderate sunlight, smog, smoke and sweat, thus significantly chancing the original color of the guitar. Yellowed Olympic White Telecasters are a classic example of yellowing phenomenon. These guitars are often confused with the Blonde ones, but you can easily distinguish between them because Blond was a transparent finish, used on ash bodies emphasize its grain patterns.

However, not all Telecasters featured a clear coat, especially if it was necessary to speed up production to satisfy all orders. Since ’62-’63, when requests had begun to increase significantly, this habit became more frequent. Guitars without the clear coat can be distinguished because they don't yellow, as vintage Olympic White Telecasters that are still white today can demonstrate.

The under coat was used to the finishing process to make it more efficient and saving money. Since the end of the '50s, Fender had often used a transparent sealer to fill the pores creating a seal that prevents following coats from soaking into the wood, thus saving color paint and money. Sealer was particularly useful with the ash, which is a very porous wood.

The very first prototypes featured a thick white acrylic enamel paint coat without any type of gloss clear coat, whilst some pre-production guitars were finished with a thick coat that doesn’t seem the typical nitrocellulose lacquer.

The clear coat was a transparent nitro layer - never acrylic - usually used on both sunburst and custom color Telecasters, but above all on the custom metallic colors. Indeed, their inorganic pigments derived from various metallic ores, will oxidize easily if they don't have a protective clear coat over them. Hence, metallic finishes had always to be clear coated, where the pastel colors didn't require it.

The celluloid-based binder in nitrocellulose clear coat yellowed over time when exposed to even moderate sunlight, smog, smoke and sweat, thus significantly chancing the original color of the guitar. Yellowed Olympic White Telecasters are a classic example of yellowing phenomenon. These guitars are often confused with the Blonde ones, but you can easily distinguish between them because Blond was a transparent finish, used on ash bodies emphasize its grain patterns.

However, not all Telecasters featured a clear coat, especially if it was necessary to speed up production to satisfy all orders. Since ’62-’63, when requests had begun to increase significantly, this habit became more frequent. Guitars without the clear coat can be distinguished because they don't yellow, as vintage Olympic White Telecasters that are still white today can demonstrate.

The under coat was used to the finishing process to make it more efficient and saving money. Since the end of the '50s, Fender had often used a transparent sealer to fill the pores creating a seal that prevents following coats from soaking into the wood, thus saving color paint and money. Sealer was particularly useful with the ash, which is a very porous wood.

The very first prototypes featured a thick white acrylic enamel paint coat without any type of gloss clear coat, whilst some pre-production guitars were finished with a thick coat that doesn’t seem the typical nitrocellulose lacquer.

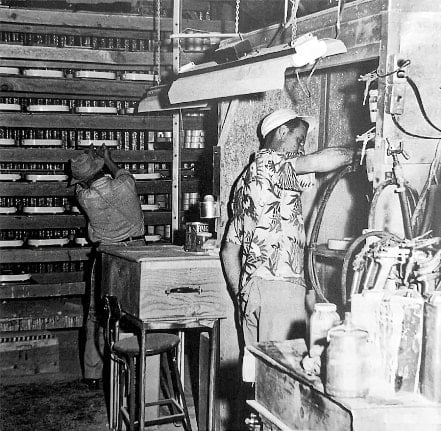

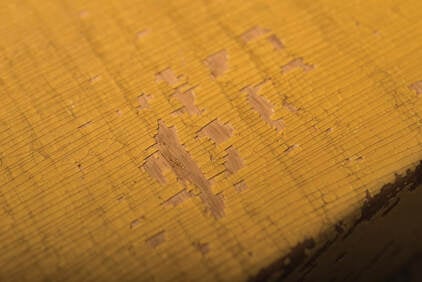

The characteristic “flacky” appearance of a 1950 Broadcaster finish, Courtesy of Cesco's Corner

The characteristic “flacky” appearance of a 1950 Broadcaster finish, Courtesy of Cesco's Corner

According to Leo Fender’s note, first production Telecaster-style guitars featured five thinner different coats: Duco primer, Dupont pore filler (applied with a spatula or brushed on), blonde stain (a mixture that contained Harper’s stain and Duco primer), Duco sealer and Duco clear coat.

Many early Broadcasters featured a characteristic “flacky” appearance because the paint was not properly anchored to the wood with a primer coat, which would have made color and clear coats adhere better.

Later November of 1950 Broadcasters seems to have a thinner finish coat.

Most 1950 Esquires and Broadcasters featured lighter finish spots, often located near the body edges and around the control plate. These spots were caused by moisture trapped into the lacquer and were performed at the factory after assembly and before guitars were shipped. Some of the early guitars needed some re-routing work and small dings and scratches usually occurred. Therefore, guitars needed other sanding and re-spraying jobs. The refinished areas never dried properly before the guitars were shipped and when exposed to sunlight, they started to show a visual light glow effect, as the clear coat aged and yellowed.

Many early Broadcasters featured a characteristic “flacky” appearance because the paint was not properly anchored to the wood with a primer coat, which would have made color and clear coats adhere better.

Later November of 1950 Broadcasters seems to have a thinner finish coat.

Most 1950 Esquires and Broadcasters featured lighter finish spots, often located near the body edges and around the control plate. These spots were caused by moisture trapped into the lacquer and were performed at the factory after assembly and before guitars were shipped. Some of the early guitars needed some re-routing work and small dings and scratches usually occurred. Therefore, guitars needed other sanding and re-spraying jobs. The refinished areas never dried properly before the guitars were shipped and when exposed to sunlight, they started to show a visual light glow effect, as the clear coat aged and yellowed.

Later Fender changed the way they apply the finish in order to save time and costs. A mixture that contained nitro and sand was also used as sealer. Guitars thus treated can be spotted thanks to the three-dimensional patterns they have when observed in the sunlight.

Later, Fender had used other sealers, like the Homoclad, or, since 1962, the Fullerplast, that “encapsulated” the body just like the polyester paints used in the CBS period did. The Fullerplast, which takes its name from that of its inventor, Fuller O'Brien, was transparent, it dried very quickly, could be applied very thin and soaked into the wood. This prevented the colors applied later from being absorbed by the wood and allowed to have a thinner layer of paint, thus saving time and material.

The appearance of some '55 and '56 Telecasters suggest that experiments might have been conducted with different filler pastes and/or undercoats prior to applying the color coat. At any rate, the ash grain pattern is more visibly showcased on early '50s guitars than on late '50s ones.

During the '60s, Fender discontinuously used a white primer undercoat to make custom color adhere better and applied in less quantity, ensuring money savings. Of course, the financial disadvantage to using a primer undercoat was it took more time, because it implied another step where they had to let the body dry. So when the production schedule allowed and they had the time to use a primer undercoat, they did. Depending on the color, if they didn't have the time or were backordered, they avoided using the primer.

Fender also used Sunburst, alone or under a white primer, as an undercoat to custom colors. Stripping an existing Sunburst bad finish to apply another was just too much work. So, shooting a new custom color directly over a rejected body allowed to save time and money. Other times it was the customer who explicitly requested, at the time of purchase and with a 5% surcharge, that the instrument be repainted with a custom color. This option could be requested both in the US and in Europe at the official distributors that received the original paints directly from the Fender factory. These factory or dealers refin are recognizable thanks to the large identification numbers imprinted on the body or on the neck (in the US) or to small stamps under the neck plate or in the neck pocket (in Europe) which allowed recognition and the return to the owner of the instrument.

Later, Fender had used other sealers, like the Homoclad, or, since 1962, the Fullerplast, that “encapsulated” the body just like the polyester paints used in the CBS period did. The Fullerplast, which takes its name from that of its inventor, Fuller O'Brien, was transparent, it dried very quickly, could be applied very thin and soaked into the wood. This prevented the colors applied later from being absorbed by the wood and allowed to have a thinner layer of paint, thus saving time and material.

The appearance of some '55 and '56 Telecasters suggest that experiments might have been conducted with different filler pastes and/or undercoats prior to applying the color coat. At any rate, the ash grain pattern is more visibly showcased on early '50s guitars than on late '50s ones.

During the '60s, Fender discontinuously used a white primer undercoat to make custom color adhere better and applied in less quantity, ensuring money savings. Of course, the financial disadvantage to using a primer undercoat was it took more time, because it implied another step where they had to let the body dry. So when the production schedule allowed and they had the time to use a primer undercoat, they did. Depending on the color, if they didn't have the time or were backordered, they avoided using the primer.

Fender also used Sunburst, alone or under a white primer, as an undercoat to custom colors. Stripping an existing Sunburst bad finish to apply another was just too much work. So, shooting a new custom color directly over a rejected body allowed to save time and money. Other times it was the customer who explicitly requested, at the time of purchase and with a 5% surcharge, that the instrument be repainted with a custom color. This option could be requested both in the US and in Europe at the official distributors that received the original paints directly from the Fender factory. These factory or dealers refin are recognizable thanks to the large identification numbers imprinted on the body or on the neck (in the US) or to small stamps under the neck plate or in the neck pocket (in Europe) which allowed recognition and the return to the owner of the instrument.

NAIL HOLES AND PAINT STICK

All Telecaster bodies that date from before the autumn of 1964 had three or four 1/16” nail holes on the front. Fender used the nails as spacers for the painting/drying process. Before applying the finish, three or four small nails were hammered into the body face. The body was therefore arranged on a turntable called “Lazy Susan” and was painted on the top. Then the body was flipped over onto the nails in order to paint the back and sides of the body. The painted body was left on its nail legs to dry. When the finish was dry, the nails were removed, thus leaving small holes free of paint, called nail holes or clamping holes. However, since the body was rubbed out after the nails were removed, nail holes may have some white or pink rubbing compound junk in them. In late 1964 Fender changed the painting process and the nails were no more used.

Between late '62 and '63, with the purpose of rotating the body in the spray booth for easy spraying and drying operations, Fender started to use a paint stick, a piece of an electrical conduit pipe. It was screwed in the neck pocket in the two bass-side screw holes and therefore, the area under the stick in the neck pocket didn't have any paint, while, until now, it was completely painted. The other side of the stick was put around a freehand rotating tool so that the body could be turned in all directions during the painting process. It's important to bear in mind that nails were still used for the drying process, but since 1964 they were replaced by a drying tree on which the sticks could be attached, which took up less space.

POLYESTER

Until about 1968, Fender mainly used thin coats of nitrocellulose lacquers on its guitars, although some custom colors were actually done with acrylic paints. However, nitrocellulose lacquers are fairly unstable, harder to deal with and can generate dangerous toxic fumes. After CBS took over Fender, polyester finishes were brought in, primarily because they are better suited to mass production. Polyester was an aliphatic polyurethane consisting of long polyester molecules.

Already in late 1967, Fender began to replace the clear coat, made so far of many coats of nitro, with only two coats of polyester. However, the color coat was still made up of acrylic or nitro lacquers. The advantage, obviously, was a significant time savings, because polyester dried very quickly. In addition, this new material did not turn yellow over time as nitro did.

However, it should be bear in mind that not all Fender guitars were completely finished with polyester, some colors continued to have the old nitro coating. Moreover, also the front side of the headstock stayed entirely lacquer, even though the rest of the neck was polyester finished, because decals reacted with polyester. Completely nitro necks dated 1967 and 1968 are not uncommon.

In late 1971, thicker coats of polyester, used as clear coat and under coat, soon generated a major change in the look and feel of Fender guitars as the company developed its “Thick Skin” high-gloss finish, whilst finishes used on '50s and '60s instruments went down in history with the nickname “Think Skin”. Indeed, '70s bodies were sprayed with anything like 10-15 coats of polyester!

'70s were years of strong experimentation, during which numerous alternatives and combinations had been tested. For example, the Olympic White kept a nitro clear coat (with a polyester undercoat) until 1977; the sunburst also in this period was made in the same way. In short, there wasn’t a standard rule.

Already in late 1967, Fender began to replace the clear coat, made so far of many coats of nitro, with only two coats of polyester. However, the color coat was still made up of acrylic or nitro lacquers. The advantage, obviously, was a significant time savings, because polyester dried very quickly. In addition, this new material did not turn yellow over time as nitro did.

However, it should be bear in mind that not all Fender guitars were completely finished with polyester, some colors continued to have the old nitro coating. Moreover, also the front side of the headstock stayed entirely lacquer, even though the rest of the neck was polyester finished, because decals reacted with polyester. Completely nitro necks dated 1967 and 1968 are not uncommon.

In late 1971, thicker coats of polyester, used as clear coat and under coat, soon generated a major change in the look and feel of Fender guitars as the company developed its “Thick Skin” high-gloss finish, whilst finishes used on '50s and '60s instruments went down in history with the nickname “Think Skin”. Indeed, '70s bodies were sprayed with anything like 10-15 coats of polyester!

'70s were years of strong experimentation, during which numerous alternatives and combinations had been tested. For example, the Olympic White kept a nitro clear coat (with a polyester undercoat) until 1977; the sunburst also in this period was made in the same way. In short, there wasn’t a standard rule.

POLYURETHANE

By late 1981, a new type of polyurethane, thinner than the previous polyester, began to replace it for the clear coat, and shortly before the close-down of the Fullerton plant, also for the color coat. However, polyester was kept as undercoat.

The American Standard Telecaster retained the same pattern, with a polyester undercoat and polyurethane color and clear coats.

Since late 1981, however, '52 Vintage reissue Telecasters have been finished with nitrocellulose all the way up, and like the originals, it also feature a white or light grey sealer coat underneath the finish, depending upon the shade of the color coat.

The American Standard Telecaster retained the same pattern, with a polyester undercoat and polyurethane color and clear coats.

Since late 1981, however, '52 Vintage reissue Telecasters have been finished with nitrocellulose all the way up, and like the originals, it also feature a white or light grey sealer coat underneath the finish, depending upon the shade of the color coat.