|

After CBS broadcast the Beatles' first American TV appearance at the Ed Sullivan Show, on February 9, 1964, all the American kids, suddenly, wanted an electric guitar. The demands increased so much that the musical instrument companies had difficulties in keeping up with the orders and the market was invaded by many foreign brands, especially from the East.

At that time Leo was suffering from a persistent streptococcal infection and he started thinking he was no longer able to manage the expanding business. So, at first, he proposed to Don Randall that he purchase his share for 1.5 million dollars, but his partner was firmly convinced that it would be more advantageous for both to sell the company to an external buyer. |

In the mid-1960s, the Fender was the guitar brand with the highest sale and it was contacted by the Cincinnati based Baldwin Piano Company. They, however, did not want to buy the acoustic guitars and Rhodes brand; so, the negotiation failed. At a later time, as Leo and Don were planning to convert the Fender into a joint stock company, CBS entered the picture.

when did cbs buy fender?

|

On January 5, 1965, after a series of secret talks that began as early as the summer of '64, Leo Fender and Don Randall sold the various Fender divisions and subsidiaries to Columbia Record Distributors, a division of Goddard Lieberson’s powerful CBS (Columbia Broadcasting System) for $13 million – CBS was already the owner of about forty different companies, including the New York Yankees baseball team, and it had introduced the 33⅓ rpm record format.

|

Donald Randall, the former president of Fender Sales, became vice president and general manager of the new CBS Fender Musical Instrument and Fender Sales divisions, whist Leo was offered only a position as an external consultant. Obviously, CBS included a contractual clause temporarily preventing Leo from opening a new musical instrument company. Forrest White remained in office until 6 December 1966 – then, bored by CBS policy that favored profit over quality, he left the company. Don Randall left CBS in April 1969, Leo Fender terminated his 5-year contract and then quit, as did George Fullerton.

After the acquisition, new plants were built, for a total of nine buildings, where the entire production was moved, right next to the old factories, which became a simple warehouse for repair, development and storage.

Thus began the CBS Fender era, a dark period during which, due to the shift to mass production, the new management sought above all to optimize and speed up production instead of focusing on the quality of the instruments, gradually transforming the company from a refined guitars producer to a sort of assembly line interested only in profit and the capability to produce, solely, instruments that were the shadow of those realized a few years earlier, as later declared by Freddie Tavares: “We had turned into a big fancy corporation all of a sudden, where all the different departments had got their say in everything and then that was budgets, quotas and so on. They [CBS] would try to put out the stuff as fast as they could!”

By a strange twist of fate, a similar syndrome struck Gibson, after McCarty's departure in 1966, and Gretsch, after Baldwin take-over in 1967.

Later, in response to Tom Wheeler’s question regarding whether he regretted the sale, Leo Fender replied he didn’t because he couldn’t keep up with the request. Rather, he said jokingly, since the Fender had grown so much, there were so many doors to close in the evening that George Fullerton could only take care of this!

After the acquisition, new plants were built, for a total of nine buildings, where the entire production was moved, right next to the old factories, which became a simple warehouse for repair, development and storage.

Thus began the CBS Fender era, a dark period during which, due to the shift to mass production, the new management sought above all to optimize and speed up production instead of focusing on the quality of the instruments, gradually transforming the company from a refined guitars producer to a sort of assembly line interested only in profit and the capability to produce, solely, instruments that were the shadow of those realized a few years earlier, as later declared by Freddie Tavares: “We had turned into a big fancy corporation all of a sudden, where all the different departments had got their say in everything and then that was budgets, quotas and so on. They [CBS] would try to put out the stuff as fast as they could!”

By a strange twist of fate, a similar syndrome struck Gibson, after McCarty's departure in 1966, and Gretsch, after Baldwin take-over in 1967.

Later, in response to Tom Wheeler’s question regarding whether he regretted the sale, Leo Fender replied he didn’t because he couldn’t keep up with the request. Rather, he said jokingly, since the Fender had grown so much, there were so many doors to close in the evening that George Fullerton could only take care of this!

THE CBS ERA AND THE BEGINNING OF DECLINE

When the Fender brand was owned by Leo Fender, manufacturing was approached from the point of view of quality, innovation, market, and business at the same time. There weren’t as many guitars being made, and the emphasis was on quality instead of quantity. Production processes were devised that were both efficient and sustainable. After CBS took over the company, the main focus was quite the reverse — on reducing production times, cutting costs, and increasing the quantity of products on offer. CBS had viewed Fender as a mass-producer of product more than an instrument maker. And because CBS failed to invest in technology that would have allowed for high quality along with high output, every aspect of guitar building - from shaping necks and bodies to drilling, routing, and mounting hardware - suffered greatly.

|

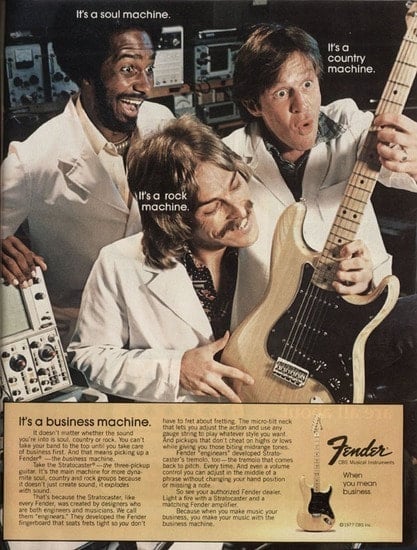

Even if CBS formally acquired the Fender on January 5, 1965, it took a little longer to see its real impact on the Stratocaster and the transition to mass production. With several “improvements” to the Stratocaster’s original design, the CBS altered its basic structure and the new guitars couldn’t measure up to the pre-CBS ones, even though a few ideas like the late ’71 micro-tilt or the 5-way switch introduced in 1977 were valid. Given that production reached almost 500 instruments a day by the end of the ‘70s, the problem was more likely in execution than design, and the decline of quality control may have been the consequence of corporate pressure to maximize profits. Quality control men had to inspect a minimum of 200 guitars a day, five days a week, and if the CBS needed the guitars, they had to be shipped, it didn’t matter if they were rejected for finish cracks or necks were bowed away too far to fix with the truss rod.

Additional cosmetic changes put even more distance between the new Stratocaster and the old ones, and the seeds of the rise of the vintage market were planted. |

As the new Stratocasters began to look less cool, old Stratocasters looked cooler than ever, and, ironically, some of the biggest competitors for the CBS guitars were the old Stratocasters.

Aside from the growth of vintage market, at the end of the '70s the trend of customizing stock Fender guitars with replacement parts bought from specialty suppliers flared up among guitarists, who were convinced that their new guitars were not as good as they could have been. This made Di Marzio’s and Seymour Duncan’s fortune, as they invaded the market with their pickups. Brass hardware was also very successful as it was thought to improve sustain.

All signs that something was going wrong with the new CBS management.

Antonio Calvosa

Aside from the growth of vintage market, at the end of the '70s the trend of customizing stock Fender guitars with replacement parts bought from specialty suppliers flared up among guitarists, who were convinced that their new guitars were not as good as they could have been. This made Di Marzio’s and Seymour Duncan’s fortune, as they invaded the market with their pickups. Brass hardware was also very successful as it was thought to improve sustain.

All signs that something was going wrong with the new CBS management.

Antonio Calvosa