THE FIRST AGED FENDER INSTRUMENTS

One of the most important Fender achievements in the second half of the '90s was relic instruments; brand new guitars that appear already used, played for a long time, and sometimes even mishandled.

This concept wasn’t new when the Fender Custom Shop started selling aged guitars: many luthiers indeed, used to age instruments either to match the repairs made to valuable vintage guitars to look like the original, or to create fakes.

The first aged Fenders date back to the '80s when Dan Smith and John Hill were using their own sources to take the finish off necks and clone those of historic guitars for some of the most influential guitar players.

This concept wasn’t new when the Fender Custom Shop started selling aged guitars: many luthiers indeed, used to age instruments either to match the repairs made to valuable vintage guitars to look like the original, or to create fakes.

The first aged Fenders date back to the '80s when Dan Smith and John Hill were using their own sources to take the finish off necks and clone those of historic guitars for some of the most influential guitar players.

|

“Antiquing” - as Dan and John called “Relicing” at that time - started as an artist A&R customizing process. This name is due to Robbie Gladwell’s workshop in England, where John took a neck made for Eric Clapton to age it because the guitarist didn’t want to play a guitar that looked or felt new. Dan and John called this process antiquing as Gladwell’s workshop was like that of a charming TV Antiques dealer played by Ian McShane in Lovejoy who ‘aged’ furniture to make it look older than it actually was!

|

However, many other players asked for aged guitars: David Gilmour, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Keith Richards, Ritchie Blackmore, George Harrison, Mick Ralphs, Andy Summers, Dave Murray and Sting.

Dan Smith and John Hill fought many corporate battles with Bill Schultz about new aged models which Bill called forgery. So reliced guitars were not manufactured for mass production until the '90s, when Jay. W. Black, Vince Cunetto and John Black came into the picture.

Dan Smith and John Hill fought many corporate battles with Bill Schultz about new aged models which Bill called forgery. So reliced guitars were not manufactured for mass production until the '90s, when Jay. W. Black, Vince Cunetto and John Black came into the picture.

VINCE CUNETTO AND JAY W. BLACK

Jay W. Black was hired by John Page as a master builder at the Custom Shop in 1989. Black had no call to put relicing into practice with Fender until the early '90s, when Don Was, who would be performing with Bonnie Raitt at the Grammys, demanded a new bass with a more used appearance. Black’s imagination was stimulated by this request, and he began to wonder if setting up a new line of guitars that showed signs of aging could be a good idea or make people laugh at him.

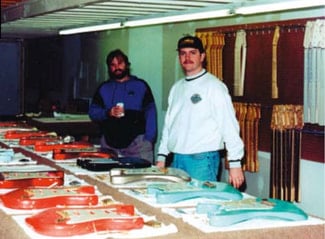

Vince Cunetto and John Page in the '90s

Vince Cunetto and John Page in the '90s

Black then decided to contact Vince Cunetto, who didn’t work yet as a guitar maker when he met the Master Builder, although he already had a long and deep passion for creating vintage-style electric guitars. “I started trading, buying and selling vintage guitars on the side in about 1984 or 1985,” Vince stated in an interview with Dave Hunter (Guitar Magazine). “I got hit with the bug to have a vintage Telecaster of my own, but I couldn’t afford any of the ones I was trading myself, so I started farting around with trying to age guitars in the mid '80s – doing a lot of research into Teles and blueprinting them. I’d borrow Telecasters from Jim Colclasure [a famed vintage guitar dealer in Kansas City] and I’d machine pin-router templates, and I’d buy the wood and I’d take it to a company that had a nice old pin-routing machine, and I started making Tele bodies. Then I started finishing them. When I was a kid I had worked in this body shop, and that’s how I learned to spray lacquer.”

Vince figured out the process of duplicating old decals from actual photographs, getting them scaled correctly, and making these really dead-nuts decals and began selling them during guitar shows, catching the attention of J.W. Black, who was already working for the Custom Shop: “We know you’re the guy making these decals, and it’s not cool, but if you quit doing that and you make them for the Custom Shop the way you made them for everybody else, it will be cool!”, declared the Master Builder.

So Cunetto began to work for the Fender Custom Shop, making period-correct logo decals for one-offs and short runs, and aged parts, like the distressed pickguard used by Black to restore Ron Wood’s vintage Broadcaster.

Vince figured out the process of duplicating old decals from actual photographs, getting them scaled correctly, and making these really dead-nuts decals and began selling them during guitar shows, catching the attention of J.W. Black, who was already working for the Custom Shop: “We know you’re the guy making these decals, and it’s not cool, but if you quit doing that and you make them for the Custom Shop the way you made them for everybody else, it will be cool!”, declared the Master Builder.

So Cunetto began to work for the Fender Custom Shop, making period-correct logo decals for one-offs and short runs, and aged parts, like the distressed pickguard used by Black to restore Ron Wood’s vintage Broadcaster.

It was just a short step from just making decals or other aged components, to aging full instruments.

Vince decided to show John Page, chief of the Custom Shop, a Stratocaster Shoreline Gold he had already aged, in order to convince him to open a line of relic instruments. Actually, it did not prove very difficult to persuade him: “If people bought distressed leather jackets, jeans and reproduction antiques, why not guitars?”, John Page remembers. “All the parts and finish on the guitar were aged and patina’d to look like an authentic vintage instrument. It was very convincing,” Black recalls.

John then decided to make an attempt, without saying anything to anyone, both to test people’s reaction and because he wasn’t sure that Fender leaders would have appreciated the idea. He asked Vince to age a couple of prototypes for the 1995 Winter NAMM Show: a '50s Butterscotch Blonde Nocaster and a '57 Stratocaster in Two-tone Sunburst.

But, by the end of 1994, Black and Page opted to change the '57 prototype to a Mary Kaye with gold hardware. So Vince completed a few prototypes displaying different levels of wear. Black and Page selected one Butterscotch Blonde Nocaster and one Mary Kaye Strat. To prevent counterfeit or confusion among the public, Page made up steel stamps to emboss the word "Relic" inside the bodies and the Custom Shop logo on the backs of the headstocks.

These instruments were exhibited inside a showcase at NAMM, suggesting that they were really two old collectible guitars. Nobody noticed the trick and when the real nature of the two instruments was revealed Fender received hundreds of orders. Mike Lewis, head of Fender marketing department at the time, said: “Hell yeah, we’re going to do this! Who wouldn’t want to play this?”

Vince decided to show John Page, chief of the Custom Shop, a Stratocaster Shoreline Gold he had already aged, in order to convince him to open a line of relic instruments. Actually, it did not prove very difficult to persuade him: “If people bought distressed leather jackets, jeans and reproduction antiques, why not guitars?”, John Page remembers. “All the parts and finish on the guitar were aged and patina’d to look like an authentic vintage instrument. It was very convincing,” Black recalls.

John then decided to make an attempt, without saying anything to anyone, both to test people’s reaction and because he wasn’t sure that Fender leaders would have appreciated the idea. He asked Vince to age a couple of prototypes for the 1995 Winter NAMM Show: a '50s Butterscotch Blonde Nocaster and a '57 Stratocaster in Two-tone Sunburst.

But, by the end of 1994, Black and Page opted to change the '57 prototype to a Mary Kaye with gold hardware. So Vince completed a few prototypes displaying different levels of wear. Black and Page selected one Butterscotch Blonde Nocaster and one Mary Kaye Strat. To prevent counterfeit or confusion among the public, Page made up steel stamps to emboss the word "Relic" inside the bodies and the Custom Shop logo on the backs of the headstocks.

These instruments were exhibited inside a showcase at NAMM, suggesting that they were really two old collectible guitars. Nobody noticed the trick and when the real nature of the two instruments was revealed Fender received hundreds of orders. Mike Lewis, head of Fender marketing department at the time, said: “Hell yeah, we’re going to do this! Who wouldn’t want to play this?”

THE CUNETTO CREATIVE RESOURCES

|

In the spring of 1995, in agreement with Page, Cunetto began to work with a couple of assistants, Tony Morford and Terri Shaw, in his lab in Bolivar, Missouri, Cunetto Creative Resources, where Fender every week sent boxes with parts for 20 guitars - bodies, necks and all the components that had to be aged. On June 27 of the same year Vince sent to Fender the first batch of aged "kits" that would have composed twenty relic Nocasters ready to be assembled.

Sales grew steadily, and the Relic Series was firmly established as a mainstream production line in the Custom Shop catalogue. |

In 1996, Cunetto put together a larger facility, where he and his team were sending 40 kits of aged instruments parts to Fender per week.

Vince worked the wood as it was once done, when Leo was still at the head of the company, sanding everything by hand. He used a slightly yellowed clear coat to imitate the finish aging and found a way to reproduce, in the most natural way possible, the cracks often visible on the surface of the old guitar. Vince studied the old Fenders as an archaeologist: why were body or neck more marked in one place than in another, why were saddles more oxidized at the low strings instead of near the high ones? - he wondered. He was not convinced that aging could improve the sound of the instruments, nor that the nitro lacquers helped improve quality. For him, the paint thickness held much more importance, but he loved nitrocellulose because of the appearance it gave to the instruments, and he possessed all the old formulas of Fender color charts.

Vince worked the wood as it was once done, when Leo was still at the head of the company, sanding everything by hand. He used a slightly yellowed clear coat to imitate the finish aging and found a way to reproduce, in the most natural way possible, the cracks often visible on the surface of the old guitar. Vince studied the old Fenders as an archaeologist: why were body or neck more marked in one place than in another, why were saddles more oxidized at the low strings instead of near the high ones? - he wondered. He was not convinced that aging could improve the sound of the instruments, nor that the nitro lacquers helped improve quality. For him, the paint thickness held much more importance, but he loved nitrocellulose because of the appearance it gave to the instruments, and he possessed all the old formulas of Fender color charts.

the last batch

Things started to change in 1998, when a part of the Custom Shop was moved to the facility that would have become the new Cessna Circle factory, Corona, and when John Page, who became the first Executive Director of Fender Museum of Music and Arts, resigned in November 1998 and was replaced by Mike Eldred. In that period Fender began to invest heavily in new paints and in new ways to apply nitro lacquers without going against California's harsh anti-pollution rules. At the same time Fender started to study and define own techniques to age the instruments.

The relationship between Fender and Vince Cunetto lasted until 1999.

Fender began its production of relic guitars in the Corona plant, after a transition period of about six months during which the instruments continued to be aged in both the places. Between May and June 1999 the last relic batch of the Cunetto era were sent to Fender.

Vince took his own way by inaugurating, in 2003, the Vinetto Guitars, while J.W. Black left the Californian company in 2002 and moved in Oregon, where he specialized in repairs to vintage Fenders and other guitars, and began to make his own F-style guitars.

The relationship between Fender and Vince Cunetto lasted until 1999.

Fender began its production of relic guitars in the Corona plant, after a transition period of about six months during which the instruments continued to be aged in both the places. Between May and June 1999 the last relic batch of the Cunetto era were sent to Fender.

Vince took his own way by inaugurating, in 2003, the Vinetto Guitars, while J.W. Black left the Californian company in 2002 and moved in Oregon, where he specialized in repairs to vintage Fenders and other guitars, and began to make his own F-style guitars.

HOW TO SPOT A FENDER BY CUNETTO?

It is interesting to note that none of Vince's secrets were shared with the Custom Shop, thus making Cunetto Stratocasters particularly desirable by collectors.

|

In order to distinguish a Stratocaster Relic of the Cunetto era from that of the next period, just look at the back side of the headstock. On the Cunetto guitars the Custom Shop logo is embossed, while in those made in the Custom Shop are simply printed. Moreover, Cunetto and his assistants dated the components with a stamp indicating year, day of the year and lot (Y-DDD-LL). For example, the 714219 code stood for “on the 142nd day of 1997, lot 19”. Towards the last period of the Cunetto era, some parts began to be dated also with the month/day/year code (MM/DD/YY).

|

Antonio Calvosa