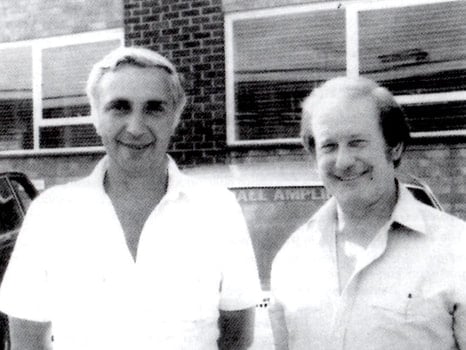

A later Marshall's shop at 146-148 Queensway in Bletchley

(Photo courtesy of Marshall)

A later Marshall's shop at 146-148 Queensway in Bletchley

(Photo courtesy of Marshall)

It was far off 1962 and in a small shop in Hanwell, a suburb on the outskirts of London, the history of rock was about to change, opening the way to “British crunch” and to the sharp, distorted sound of Jimi Hendrix’s Stratocaster. However, what was unexpected was that this small shop at 76 Uxbridge Road, at least initially, wasn’t a guitar or amplifier store, but a drum store that the maestro, Jim Marshall decided to open on 7 July 1960: the Jim Marshall & Son.

Over half a century has gone by and the exact details about the creation of one of the most important blues and rock amplifiers are vague and subject to varying opinions. According to the official version recounted by Jim and his son Terry Marshall, a lot of drum players brought guitarists and bass players from their groups to the shop, so Jim decided to expand the store with a guitar, bass and amplifiers section. There were brands such as Fender, Gibson, Selmer, Watkins and Vox. In 1961 Jim employed Terry’s friend, Mick Borer, who had been guitarist in the Cliff Bennet and the Rebel Rousers band and in 1962, Ken Bran as technician. At that time musical instrument shops were dedicated to jazz or orchestral music, therefore Marshall's shop quickly became famous among teenagers and youngsters who were ever increasingly moving towards rock

Over half a century has gone by and the exact details about the creation of one of the most important blues and rock amplifiers are vague and subject to varying opinions. According to the official version recounted by Jim and his son Terry Marshall, a lot of drum players brought guitarists and bass players from their groups to the shop, so Jim decided to expand the store with a guitar, bass and amplifiers section. There were brands such as Fender, Gibson, Selmer, Watkins and Vox. In 1961 Jim employed Terry’s friend, Mick Borer, who had been guitarist in the Cliff Bennet and the Rebel Rousers band and in 1962, Ken Bran as technician. At that time musical instrument shops were dedicated to jazz or orchestral music, therefore Marshall's shop quickly became famous among teenagers and youngsters who were ever increasingly moving towards rock

It was Ken who suggested to Jim to employ his resources in building his own amplifier rather than importing the very expensive Fenders from the USA. Jim listened carefully to the needs of the guitarists who went to the shop. Encouraged by Terry, Mick and another friend of theirs, the young Pete Townshend, who all dreamed of a new amplifier with a different sound and higher power, he accepted Ken’s proposal. However, despite his experience in repairing electronic equipment, Ken didn’t feel up to building the new amplifier on his own and asked his friend, the eighteen year old Dudley Craven to help him as an external consultant. Dudley was a radio amateur who worked as an apprentice at EMI Electronics where he was known as a “Whiz kid” in the electronic field because of his excellence, despite his young age. Together with Ken Bran, he had harboured the idea of building his own amplifier, for some time. We have to partly give credit to Dudley for the Marshall’s having been truly innovative and having such a different sound to the Fenders.

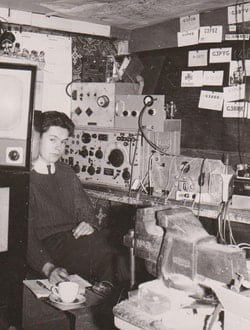

The 17 year old Dudley Craven in his shed, 1961

The 17 year old Dudley Craven in his shed, 1961

Under Ken Bran’s supervision, Dudley began designing the first prototypes of the future JTM45, with the collaboration of two of his old school friends, Ken Flegg and Richard “Dick” Findlay. Since there wasn’t much space in Jim’s shop, Dudley worked on the new amplifier, in a small shed from which he transmitted as radio amateur under the name “G3PUN”. The shed was behind his house at 202C Uxbridge Road. In the meantime, Ken often worked in his “bedroom” at Wembley. Therefore we can safely say that the construction of the first Marshall prototype took place anywhere but in Jim’s shop!

The basis for their idea came from the Fender Bassman. But while Terry and his friends preferred the Piggyback Bassman, which consisted of a head with a 2x12 cabinet, Ken Bran and Jim preferred the tweed 1959 Bassman combo with 4x10" speakers. The compromise was found by Ken who put the 1959 Fender circuit (the 5F6A) into the amp head.

The basis for their idea came from the Fender Bassman. But while Terry and his friends preferred the Piggyback Bassman, which consisted of a head with a 2x12 cabinet, Ken Bran and Jim preferred the tweed 1959 Bassman combo with 4x10" speakers. The compromise was found by Ken who put the 1959 Fender circuit (the 5F6A) into the amp head.

Jim Marshall's group produced one prototype a week, which was tested with the collaboration of Pete Townshend, Ritchie Blackmore, John Entwistle and Jim Sullivan, a well known London session musician at the time. It was the sixth prototype that immediately convinced Jim. This first unit, which was initially called “Number 1 Amp”, had the same circuit as the Fender 5F6A Bassman (with a bright cap), but also had some small but substantial differences, due both to a different availability of components in the British market compared to the American one, but also to technical choices. The idea, in fact, was not simply to copy a Fender, but to improve it: their motto was “like a Fender, but much more.” And the result of their first amplifier was just that, the “Marshall sound” that Jim had in mind: grittier and harsher than the Bassman, but also richer and sweeter. A whole new sound, even more powerful than its British “cousin” Vox AC30. A bright, sharp sound on the first channel, darker, wormer on the second.

The prototype Number 1 Amp showed, on the front panel, a different arrangement of knobs than later productions and similar to that of Bassman (in order: presence, middle, bass, treble) and, like the very first official models, did not yet have the writing “JTM45” or “MK II”. So, as the very first JTM45 built, it can be called “MK I”, unlike those that, a little later, would have the writing “MK II” on the front panel. To understand how few MK I’s there were, just consider that the serial numbers of the Marshalls began from the number 1001 and, on the amplifier with the serial number 1037, was already printed “MK II”.

The prototype displayed in the window was initially sold to a young boy who walked into the store with his father. He absolutely wanted one of these amps, but given the long waiting time due to numerous orders, he got permission from Jim to purchase the Number 1 Amp. Many weeks later though, after production was in full swing, being very attracted to the look of the JTM45, he returned and exchanged it for a new one. Once back in possession of the prototype, Jim locked it in a box and put it in a basement. Some famous musicians, including Gary Moore, later asked him if they could buy it, but Jim always refused. Currently the sixth prototype is in the Marshall Museum in Bletchley.

In the first week alone Jim received twenty-three orders for the new amplifier. The success of the JTM45 was such that in a short time the production of the cabinets was moved, first to a second store at 93 Uxbridge Road and then to a small warehouse in Southall, Middlesex, before the opening, in June 1964, of the first real Marshall factory in Silverdale Road, in the Hayes district. At least fifteen employees worked there, producing about twenty amplifiers per week.

The prototype Number 1 Amp showed, on the front panel, a different arrangement of knobs than later productions and similar to that of Bassman (in order: presence, middle, bass, treble) and, like the very first official models, did not yet have the writing “JTM45” or “MK II”. So, as the very first JTM45 built, it can be called “MK I”, unlike those that, a little later, would have the writing “MK II” on the front panel. To understand how few MK I’s there were, just consider that the serial numbers of the Marshalls began from the number 1001 and, on the amplifier with the serial number 1037, was already printed “MK II”.

The prototype displayed in the window was initially sold to a young boy who walked into the store with his father. He absolutely wanted one of these amps, but given the long waiting time due to numerous orders, he got permission from Jim to purchase the Number 1 Amp. Many weeks later though, after production was in full swing, being very attracted to the look of the JTM45, he returned and exchanged it for a new one. Once back in possession of the prototype, Jim locked it in a box and put it in a basement. Some famous musicians, including Gary Moore, later asked him if they could buy it, but Jim always refused. Currently the sixth prototype is in the Marshall Museum in Bletchley.

In the first week alone Jim received twenty-three orders for the new amplifier. The success of the JTM45 was such that in a short time the production of the cabinets was moved, first to a second store at 93 Uxbridge Road and then to a small warehouse in Southall, Middlesex, before the opening, in June 1964, of the first real Marshall factory in Silverdale Road, in the Hayes district. At least fifteen employees worked there, producing about twenty amplifiers per week.

By the mid '60s, every major British musician and band was playing with a Marshall, with the unbelievable exceptions of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. A few years later, even the most famous guitarist of all time, Jimi Hendrix, chose Marshall.

Hendrix met Jim through his drummer, Mitch Mitchell, who occasionally worked in Marshall's store on Saturday evenings. Jim remembers that Mitch told him about this new American guitarist, who had recently arrived in London and whose name was James Marshall Hendrix and who absolutely wanted to meet him because they almost had the same name and all his idols, especially Clapton, played with a Marshall. Jim was very impressed by Jimi Hendrix's humility when, unlike most London guitarists who presumed to be "the best guitarists in the world" and therefore wanted something in return for playing with his amps, Hendrix wanted to pay for his equipment in full.

Hendrix met Jim through his drummer, Mitch Mitchell, who occasionally worked in Marshall's store on Saturday evenings. Jim remembers that Mitch told him about this new American guitarist, who had recently arrived in London and whose name was James Marshall Hendrix and who absolutely wanted to meet him because they almost had the same name and all his idols, especially Clapton, played with a Marshall. Jim was very impressed by Jimi Hendrix's humility when, unlike most London guitarists who presumed to be "the best guitarists in the world" and therefore wanted something in return for playing with his amps, Hendrix wanted to pay for his equipment in full.

Also worth considering is the slightly different version reported by Ken Underwood, on the Vintage Amps Forum. The story, Underwood says, was that prior to any Jim Marshall involvement, Dudley Craven was already collaborating with Richard "Dick" Findlay on the construction of one of his amps. Later, Ken Bran took part in the project to go over the technical aspects with Craven; finally, in '63, Ken Underwood, also an apprentice at EMI at the time, joined the group, helping to assemble the major mechanical components to the chassis.

According to Underwood, the very first amp was tested on a Saturday night in '63 at the Ealing Club by a group that also included Mitch Mitchell, future drummer for Jimi Hendrix's Experience, Dave Golding on sax, Kenny Rankin on bass, and Jimmy Royal on guitar and vocals. The band's set list for the evening also included a cover of a recently released Beatles song, “I Saw Her Standing There,” which was not released in '62, but on March 22, 1963. According to the band's feedback, the group of friends made some changes to the model tested at the Ealing Club which led to the creation of the first real amplifier which therefore, could not have already been sold, as Jim Marshall claimed, in '62 to Pete Townshend.

In fact, it was only at this time, according to Underwood, that Jim Marshall, an old friend of Ken Bran's, came into play. Craven, Bran and Underwood relied on Marshall's store to sell their first amps. Jim sniffed out the deal and in 1964 suggested they finance them and join him, therefore naming the new amplifier after himself.

While Craven was happy to leave EMI to work in the field of amplifiers, Underwood, still underaged, sought advice from his mother who preferred a more stable and secure job for him, suggesting that he continue his apprenticeship at EMI, without knowing what the future would hold for Marshall. Findlay also preferred not to be officially involved but to remain only an outside consultant.

Ken and Dudley went to work in the back of Jim's store on production, in early 1964. However, just a few months later, demand was so high that they had to open the Silverdale Road factory.

This story was the focus of heated debates among Jim's supporters and Underwood's supporters. Marshall himself intimated to Underwood in numerous emails to “go stick your nose somewhere else.”

According to Underwood, the very first amp was tested on a Saturday night in '63 at the Ealing Club by a group that also included Mitch Mitchell, future drummer for Jimi Hendrix's Experience, Dave Golding on sax, Kenny Rankin on bass, and Jimmy Royal on guitar and vocals. The band's set list for the evening also included a cover of a recently released Beatles song, “I Saw Her Standing There,” which was not released in '62, but on March 22, 1963. According to the band's feedback, the group of friends made some changes to the model tested at the Ealing Club which led to the creation of the first real amplifier which therefore, could not have already been sold, as Jim Marshall claimed, in '62 to Pete Townshend.

In fact, it was only at this time, according to Underwood, that Jim Marshall, an old friend of Ken Bran's, came into play. Craven, Bran and Underwood relied on Marshall's store to sell their first amps. Jim sniffed out the deal and in 1964 suggested they finance them and join him, therefore naming the new amplifier after himself.

While Craven was happy to leave EMI to work in the field of amplifiers, Underwood, still underaged, sought advice from his mother who preferred a more stable and secure job for him, suggesting that he continue his apprenticeship at EMI, without knowing what the future would hold for Marshall. Findlay also preferred not to be officially involved but to remain only an outside consultant.

Ken and Dudley went to work in the back of Jim's store on production, in early 1964. However, just a few months later, demand was so high that they had to open the Silverdale Road factory.

This story was the focus of heated debates among Jim's supporters and Underwood's supporters. Marshall himself intimated to Underwood in numerous emails to “go stick your nose somewhere else.”

The term “JTM45” with which the new amplifier would soon be identified, came from the names of Jim and Terry Marshall. Actually, the meaning of "45" is unclear, as the wattage was estimated, contrary to many beliefs, to be between 30 and 35 watts.

While the preamp circuit was essentially the same as the Bassman 5F6A, the differences between the Bassman “progenitor” and the new JTM45 were numerous and profoundly altered the sound. The JTM45 featured the 12AX7 (ECC83) preamp tubes, which became saturated more easily than the Fender's first-stage 12AY7 dual triode. Contrary to what is often thought, the final valves, at least in early models, remained the same 6L6 (5881) as the Fender, to be replaced later by 6L6GT and only in '65 by the local GEC KT66 that highlighted the "British" character even more and increased the power to about 40-45 watts. The JTM45 was also equipped, until 1966, with a rectifying valve GZ34 (5AR4), which gave compression and sustain at high volumes, that characterized the sound.

Instead of the American Triad, Craven used the British Radiospares as output transformers (although some prototypes also used Elstone). Let’s not forget the different bright caps in the various versions of the JTM45 that contributed greatly to sound differentiation.

In addition, the new Marshall’s chassis was thick and made of aluminum, while the U.S. amplifiers mounted a steel one. Aluminum had the advantage of having less influence on the magnetic field of the transformers.

Impedance was increased from the Bassman's 2Ω to the JTM45's 16Ω, resulting in a feedback voltage increase of about three times.

Finally, another important difference not to be underestimated were the speakers: the Bassman combo was equipped with an open cabinet with four 10" Jensen speakers. Jim Marshall instead, after testing the prototypes with 2x12 open cabinets (which were not able to handle the power of the JTM45), preferred a closed cabinet with four 12" alnico Celestion G12 speakers. Let’s not forget, however, that between '65 and '66 the first cabinets appeared that were equipped with the famous ceramic Celestion Greenbacks, widely used in the Marshalls, and that contributed greatly to the definition of the "British sound".

The very first JTM45 also had a polarity switch, in addition to the on/off and stand-by switches, which reduced unwanted hum.

While the preamp circuit was essentially the same as the Bassman 5F6A, the differences between the Bassman “progenitor” and the new JTM45 were numerous and profoundly altered the sound. The JTM45 featured the 12AX7 (ECC83) preamp tubes, which became saturated more easily than the Fender's first-stage 12AY7 dual triode. Contrary to what is often thought, the final valves, at least in early models, remained the same 6L6 (5881) as the Fender, to be replaced later by 6L6GT and only in '65 by the local GEC KT66 that highlighted the "British" character even more and increased the power to about 40-45 watts. The JTM45 was also equipped, until 1966, with a rectifying valve GZ34 (5AR4), which gave compression and sustain at high volumes, that characterized the sound.

Instead of the American Triad, Craven used the British Radiospares as output transformers (although some prototypes also used Elstone). Let’s not forget the different bright caps in the various versions of the JTM45 that contributed greatly to sound differentiation.

In addition, the new Marshall’s chassis was thick and made of aluminum, while the U.S. amplifiers mounted a steel one. Aluminum had the advantage of having less influence on the magnetic field of the transformers.

Impedance was increased from the Bassman's 2Ω to the JTM45's 16Ω, resulting in a feedback voltage increase of about three times.

Finally, another important difference not to be underestimated were the speakers: the Bassman combo was equipped with an open cabinet with four 10" Jensen speakers. Jim Marshall instead, after testing the prototypes with 2x12 open cabinets (which were not able to handle the power of the JTM45), preferred a closed cabinet with four 12" alnico Celestion G12 speakers. Let’s not forget, however, that between '65 and '66 the first cabinets appeared that were equipped with the famous ceramic Celestion Greenbacks, widely used in the Marshalls, and that contributed greatly to the definition of the "British sound".

The very first JTM45 also had a polarity switch, in addition to the on/off and stand-by switches, which reduced unwanted hum.

The new amplifier was available in both the lead and bass versions (without bright cap and more suitable for the base), and, a little later, also in the P.A. version. They all had very slight sound differences. The P.A. version had to be equipped, on the rear panel, with two parallel outputs for the speakers instead of the single output (typical of the amplifiers of that period), a feature often adopted in later productions.

With the introduction of large KT66 tubes, which replaced the 6L6, the JTM45 lead head were identified with the model name 1987, the bass with 1986, and the P.A. with 1985.

All of these acronyms did not refer to the year of production, but were due to the prefix "19" that Rose-Morris, Jim's financier and distributor until 1990, attributed to the entire line of Marshall products.

In '65 the organ version (1989) was also introduced. It was designed for electric organs, which Marshall recommended be associated with a 4x12 guitar cab, and the tremolo version (T1987), based on the lead one, which had two additional knobs (speed and intensity) and a pedal to activate the effect. The tremolo version had a larger chassis to accommodate a transistor and an additional ECC83, and displayed “MK IV” lettering on the front panel.

With the introduction of large KT66 tubes, which replaced the 6L6, the JTM45 lead head were identified with the model name 1987, the bass with 1986, and the P.A. with 1985.

All of these acronyms did not refer to the year of production, but were due to the prefix "19" that Rose-Morris, Jim's financier and distributor until 1990, attributed to the entire line of Marshall products.

In '65 the organ version (1989) was also introduced. It was designed for electric organs, which Marshall recommended be associated with a 4x12 guitar cab, and the tremolo version (T1987), based on the lead one, which had two additional knobs (speed and intensity) and a pedal to activate the effect. The tremolo version had a larger chassis to accommodate a transistor and an additional ECC83, and displayed “MK IV” lettering on the front panel.

The appearance of the early Marshall amplifiers changed considerably in the first three years. The peculiarity of the very first models, called “Offset amps”, was that, in order to balance them and make them more easily transportable, they had the chassis and the control panel on the side of the head cabinet, that didn’t bring added advantages and was visually a bit asymmetrical. These offset amps and the ones that followed were all characterized by a metal plate with the initials “Marshall” in red enamel, purchased from Butler, a funeral items retailer in Birmingham. For this very reason, they were nicknamed “Coffin Badges”.

The chassis was encased in black eco-leather and had a front livery completely made of a blond color grill cloth, called “Vynair”, to better match the cabinets.

The chassis was encased in black eco-leather and had a front livery completely made of a blond color grill cloth, called “Vynair”, to better match the cabinets.

Later, with the shift of production to a more spacious room at 97 Uxbridge Road, both the metal plate bearing the logo, and the control panel, were placed at the center of the front of the amplifier, which soon became two-tone, a blond color at the bottom and black, thanks to a material called “Renexe”: the so-called “Sandwich Amp”.

The writing, JTM45, still hadn’t appeared but the first control panels with the initials “MK II” and “JTM45” had already been ordered. With the introduction of these initials and the elimination of the polarity switch, the space between the four inputs increased, compared to that of the first models.

Towards the end of '63 even the two-tone livery was abandoned in favor of the classic all-black Marshall front.

The logo also underwent major changes: first, a silver Plexiglas rectangle with red lettering, then black lettering on a gold rectangle. These “block logos” were abandoned in '65 with the appearance of the familiar Marshall “script logo” still in use today. At the same time the square, red LED took the place of the circular amber one.

Until ‘64 the control panel was in traffolyte or aluminum, silk-screened or engraved, and later it was produced in plexiglas, first white, then in the better known golden plexiglas, the famous “plexi panel”. So, until '64 Marshall amplifiers were in the pre-plexi era, in which the control panel was traffolyte or aluminum. In '65 the so-called plexi era began, which lasted until mid '69 when the metal paneled era came into being.

Towards the end of '63 even the two-tone livery was abandoned in favor of the classic all-black Marshall front.

The logo also underwent major changes: first, a silver Plexiglas rectangle with red lettering, then black lettering on a gold rectangle. These “block logos” were abandoned in '65 with the appearance of the familiar Marshall “script logo” still in use today. At the same time the square, red LED took the place of the circular amber one.

Until ‘64 the control panel was in traffolyte or aluminum, silk-screened or engraved, and later it was produced in plexiglas, first white, then in the better known golden plexiglas, the famous “plexi panel”. So, until '64 Marshall amplifiers were in the pre-plexi era, in which the control panel was traffolyte or aluminum. In '65 the so-called plexi era began, which lasted until mid '69 when the metal paneled era came into being.

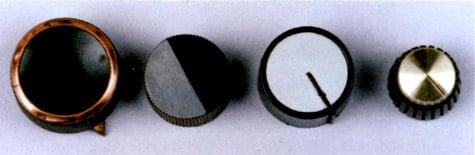

The front panel knobs also varied a lot: the first type was the Radiogram-style, black, with a small coppery circumference at the top. Then there was the angled, black V-top. The Silverface black pointer is often found on JTM45s with the block logo, and finally there was the Classic Marshall knob with the script logo amps.

Antonio Calvosa