FIRST FENDER PROTOTYPES

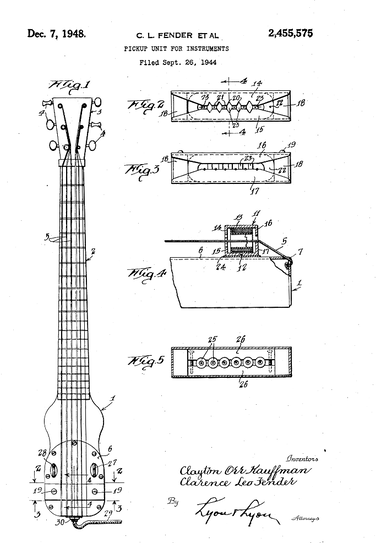

Leo Fender and Doc Kauffman filed the patent for "pickup unit for stringed instruments" on 26 September 1944, and it was approved on 7 December 1948

Leo Fender and Doc Kauffman filed the patent for "pickup unit for stringed instruments" on 26 September 1944, and it was approved on 7 December 1948

Manufacturing a better electric guitar for musicians, especially for Western music musicians, had been in Leo Fender’s mind ever since 1940. In an interview published on the Daily News Tribute of 8 November 1949, Leo stated that he’d got the idea whilst repairing a guitar in his shop; whilst taking it apart he’d understood that it could have been improved in terms of volume and timbre as well as in terms of playability.

Leo had already electrified Fred Clay’s Martin Acoustic 000-18 by adding a pickup to it, had built a Spanish electric guitar for Bob Stack and built, or electrified, at least another couple of models at the end of the 1940s. On 26 September 1944 Leo Fender and Doc Kauffman patented the “pickup unit for stringed instruments”; this pickup was designed for lap steel guitars, but in order to test it Leo had built a small instrument on which he’d assembled bridge, pickup, headstock and strings. The instrument had a rounded neck and could be played like Spanish guitars. However, Leo was too concentrated on lap steel guitars to focus fully on Spanish electric guitars.

It was only after a suggestion by his friend and product representative, Charlie Hayes, that Leo Fender realized the extent to which guitarists were in need of electric guitars that could be played at higher volumes without having feedback issues, and he started to seriously entertain the idea of building a Spanish solid-body guitar.

But Leo faced another problem, in addition to feedback, which plagued electric guitars: without compensated bridges the instruments were never in tune. In acoustic guitars the rich overtones masked the dissonances, but on electric guitars every note was laid bare and every tuning defect produced an unpleasant sound!

So, for Leo Fender, an electric guitar was not to be affected by feedback, had to have a bridge with adjustable saddles for better tuning, had to have a pickup with six separate pole pieces in order to produce a balanced response for each string (a technique already used by DeArmond) and be height-adjustable at the sides, and had to have a detachable neck secured to the body with four screws - not a completely novel idea, since detachable necks were already used in Banjos and by other brands, such as the Rickenbacker. According to Leo, the advantage of detachable necks was that they could be easily replaced. Don Randall, who at that time was general manager of Francis Hall’s Radio and Television Equipment Co. (known as Radio Tel) and who held the agreement for the exclusive distribution of Fender products, believed the real advantage would have been the ability to repair the guitar more easily, because he knew that no guitarist would willingly part with his guitar neck. Moreover, detachable necks would have allowed costs to be cut and production time to be shortened; and to further reduce production time and costs, Leo decided to use a single piece of resistant wood on which to fit the frets directly rather than a neck with a fretboard glued onto it.

Leo had already electrified Fred Clay’s Martin Acoustic 000-18 by adding a pickup to it, had built a Spanish electric guitar for Bob Stack and built, or electrified, at least another couple of models at the end of the 1940s. On 26 September 1944 Leo Fender and Doc Kauffman patented the “pickup unit for stringed instruments”; this pickup was designed for lap steel guitars, but in order to test it Leo had built a small instrument on which he’d assembled bridge, pickup, headstock and strings. The instrument had a rounded neck and could be played like Spanish guitars. However, Leo was too concentrated on lap steel guitars to focus fully on Spanish electric guitars.

It was only after a suggestion by his friend and product representative, Charlie Hayes, that Leo Fender realized the extent to which guitarists were in need of electric guitars that could be played at higher volumes without having feedback issues, and he started to seriously entertain the idea of building a Spanish solid-body guitar.

But Leo faced another problem, in addition to feedback, which plagued electric guitars: without compensated bridges the instruments were never in tune. In acoustic guitars the rich overtones masked the dissonances, but on electric guitars every note was laid bare and every tuning defect produced an unpleasant sound!

So, for Leo Fender, an electric guitar was not to be affected by feedback, had to have a bridge with adjustable saddles for better tuning, had to have a pickup with six separate pole pieces in order to produce a balanced response for each string (a technique already used by DeArmond) and be height-adjustable at the sides, and had to have a detachable neck secured to the body with four screws - not a completely novel idea, since detachable necks were already used in Banjos and by other brands, such as the Rickenbacker. According to Leo, the advantage of detachable necks was that they could be easily replaced. Don Randall, who at that time was general manager of Francis Hall’s Radio and Television Equipment Co. (known as Radio Tel) and who held the agreement for the exclusive distribution of Fender products, believed the real advantage would have been the ability to repair the guitar more easily, because he knew that no guitarist would willingly part with his guitar neck. Moreover, detachable necks would have allowed costs to be cut and production time to be shortened; and to further reduce production time and costs, Leo decided to use a single piece of resistant wood on which to fit the frets directly rather than a neck with a fretboard glued onto it.

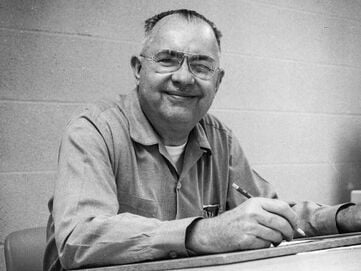

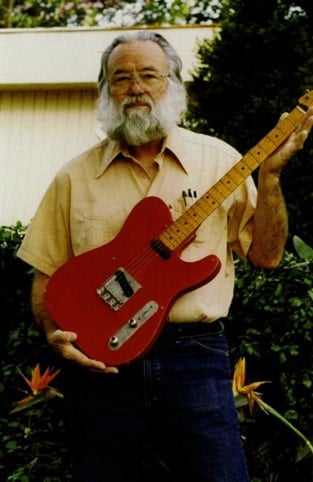

George Fullerton

George Fullerton

According to Leo Fender, above all else, the new electric guitar had to be simple to build, play and repair: “The design of everything we did was intended to be easy to built and easy to repair. When I was in the repair business, dealing with other men’s problems, I could see the shortcomings in the design completely disregarding the need for service. If a thing is easy to service, it is easy to build.”

Leo Fender couldn’t compete with brands that had a great history of guitar making behind them, or rather, he couldn’t compete at their same level: he didn’t have the means, experience, or workers to. What he could do, however, was build a Spanish solid-body guitar that was more like his lap steels than the hollow-bodies. In this way, his guitar would be of a high quality, fit for factory production and inexpensive – so suitable for most professional musicians. Moreover, the guitar would have had a completely new timbre, sharp, bright and with deep bass, without the medium frequencies that gave the instrument the grave sound which he called “fluff”. In an historical period in which guitarists were chasing the sound of Charlie Christian, Chet Atkins and Hank Garland, Leo believed that the sound of his guitar had to be closer to that of a steel one.

Even though Leo Fender never admitted it, the tips he got from the Rickenbacker owned by his friend Doc Kauffman, such as the detachable neck or its simplicity, are evident. But then again, Kauffman’s instrument had margins for improvement, both in terms of sound as well as in terms of tuning and shape.

A key role in the birth of the first Fender solid-body guitar was played by George Fullerton who, in spite of his name, had no relation to his namesake who founded the city of Fullerton. George worked as a truck-driver for a Los Angeles furniture shop, repaired radios and played the guitar in a band called Gold Coast Rangers. Fullerton first started hanging out with Leo in 1947. He had no experience in guitar making – he’d only electrified his acoustic guitar, as had many other musicians of that time – so when Leo offered him a job he was at first skeptical. Nevertheless, he accepted the job and started working for Fender on 2 February 1948. He repaired amplifiers and steel guitars, but was also a very good woodworker, and it is to him that we owe the shape of what was to later become the Telecaster. In time, Fender also employed George’s sister, brother and father.

Leo Fender couldn’t compete with brands that had a great history of guitar making behind them, or rather, he couldn’t compete at their same level: he didn’t have the means, experience, or workers to. What he could do, however, was build a Spanish solid-body guitar that was more like his lap steels than the hollow-bodies. In this way, his guitar would be of a high quality, fit for factory production and inexpensive – so suitable for most professional musicians. Moreover, the guitar would have had a completely new timbre, sharp, bright and with deep bass, without the medium frequencies that gave the instrument the grave sound which he called “fluff”. In an historical period in which guitarists were chasing the sound of Charlie Christian, Chet Atkins and Hank Garland, Leo believed that the sound of his guitar had to be closer to that of a steel one.

Even though Leo Fender never admitted it, the tips he got from the Rickenbacker owned by his friend Doc Kauffman, such as the detachable neck or its simplicity, are evident. But then again, Kauffman’s instrument had margins for improvement, both in terms of sound as well as in terms of tuning and shape.

A key role in the birth of the first Fender solid-body guitar was played by George Fullerton who, in spite of his name, had no relation to his namesake who founded the city of Fullerton. George worked as a truck-driver for a Los Angeles furniture shop, repaired radios and played the guitar in a band called Gold Coast Rangers. Fullerton first started hanging out with Leo in 1947. He had no experience in guitar making – he’d only electrified his acoustic guitar, as had many other musicians of that time – so when Leo offered him a job he was at first skeptical. Nevertheless, he accepted the job and started working for Fender on 2 February 1948. He repaired amplifiers and steel guitars, but was also a very good woodworker, and it is to him that we owe the shape of what was to later become the Telecaster. In time, Fender also employed George’s sister, brother and father.

Blow-up from a picture published on “Fender, The sound heard 'round the world” by Richard R. Smith. In the background, the template of the second prototype.

Blow-up from a picture published on “Fender, The sound heard 'round the world” by Richard R. Smith. In the background, the template of the second prototype.

Unlike what might be common belief, the first prototype of Leo Fender’s new solid-body guitar had a laminated two-piece pine body and not, therefore a single piece, cut by George, on which he then applied a thick layer of white enamel paint and a black phenolic wing-shaped pickguard in the lower half of the body.

According to Nacho Baños, author of The Blackguard, a detailed history of the early Fender Telecaster, Years 1950-1954, the second prototype had a four-piece laminated pine chambered body (not ash, as often reported) like the Rickenbacker, but it was discarded at once for its longer construction time. Its original color was white, but after a red refin, the body was completely stripped.

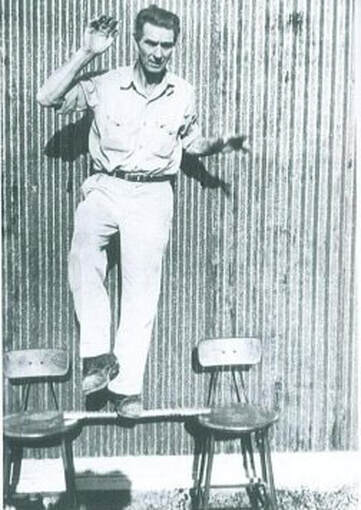

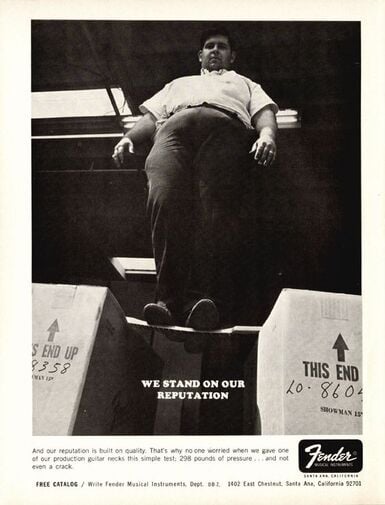

Leo chose resistant hard rock maple for the neck, which, unlike the Rickenbacker’s bakelite, was only minimally affected by sunlight or stage light temperature changes, holding the tuning much better. Leo was so sure of the resistance of this wood that he didn’t want to fit a truss rod to the neck. Indeed, there is a famous photograph showing one of his employees, Hugh Garriott, stepping on a maple guitar neck propped up between two chairs to demonstrate the resistance of Fender necks. This anecdote provided the inspiration, around 1967, for a Fender advertisement in which a worker climbed onto a guitar neck held up between two boxes with the caption, “We stand on our reputation”.

According to Nacho Baños, author of The Blackguard, a detailed history of the early Fender Telecaster, Years 1950-1954, the second prototype had a four-piece laminated pine chambered body (not ash, as often reported) like the Rickenbacker, but it was discarded at once for its longer construction time. Its original color was white, but after a red refin, the body was completely stripped.

Leo chose resistant hard rock maple for the neck, which, unlike the Rickenbacker’s bakelite, was only minimally affected by sunlight or stage light temperature changes, holding the tuning much better. Leo was so sure of the resistance of this wood that he didn’t want to fit a truss rod to the neck. Indeed, there is a famous photograph showing one of his employees, Hugh Garriott, stepping on a maple guitar neck propped up between two chairs to demonstrate the resistance of Fender necks. This anecdote provided the inspiration, around 1967, for a Fender advertisement in which a worker climbed onto a guitar neck held up between two boxes with the caption, “We stand on our reputation”.

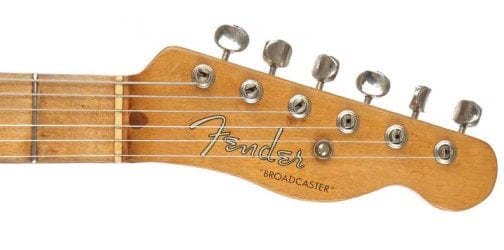

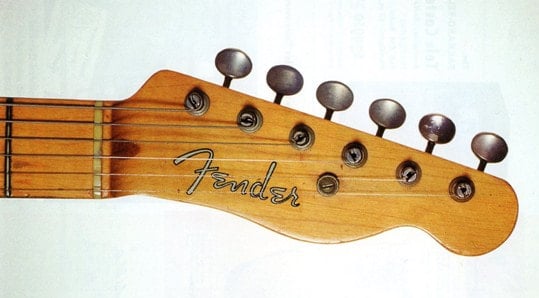

The first neck, built by George Fullerton, had a snakehead headstock with three Kluson tuning keys on each side, just like lap steel guitars, and painted fret markers. By contrast, the headstock on the second prototype was as we know it nowadays, slender and elegant, with all the machine heads on the same side – this forced Leo to cut the Klusons, since they were not intended to be fitted in a line that way. Even though Bigsby’s guitar also had all six machine heads fitted side by side, it seems that Leo in fact got the idea from a photograph of a Croatian musician playing an instrument with a similar headstock. Thanks to this design the strings ran straight from the fretboard nut to the machine heads, allowing the instrument to hold the tuning better. The second prototype currently features a replacement neck, not the original one, which has the truss rod and the string tree.

On the right, Roy "Jimmy" Watkins, with a white hat, playing the second prototype with its previous non-truss rod neck during summer 1950, in Fullerton, before it was painted red and stripped to natural.

On the right, Roy "Jimmy" Watkins, with a white hat, playing the second prototype with its previous non-truss rod neck during summer 1950, in Fullerton, before it was painted red and stripped to natural.

Both prototypes had only a Lead Pickup “fitted” into the bridge, developed by Leo at the beginning of 1949, which was very similar to the one he made for the Champion Lap Steel guitar (and which did not produce the ʺfluff” he hated so much). Leo slanted the pickup to give stronger bass tones, just as Gibson did on the ES-300. The bridge had three saddles, one every two strings; this system did not provide perfect tuning, but was a good compromise. If compared to later manufactured models made with the Race & Olmsted presses and plates, this bridge was very rough.

The control plate on the first prototype was at an angle and seemed to follow the direction of the pickup, because Leo believed this position made it more comfortable for the musician, whilst in the second prototype the plate ran perpendicular to the body. So, in neither prototype did the plate run parallel to the neck as in the production models and both were without switches. The control plate currently featured on the second prototype is not the original one, which was a crudely cut football ball shaped, but it is a standard Precision Bass control plate.

The pots on the first prototype were stamp-dated the thirty-first week of 1939, which may lead us to infer that the prototype was completed in the autumn of 1949. However, since there are no precise dates written on the instrument, the exact date is impossible to know.

The control plate on the first prototype was at an angle and seemed to follow the direction of the pickup, because Leo believed this position made it more comfortable for the musician, whilst in the second prototype the plate ran perpendicular to the body. So, in neither prototype did the plate run parallel to the neck as in the production models and both were without switches. The control plate currently featured on the second prototype is not the original one, which was a crudely cut football ball shaped, but it is a standard Precision Bass control plate.

The pots on the first prototype were stamp-dated the thirty-first week of 1939, which may lead us to infer that the prototype was completed in the autumn of 1949. However, since there are no precise dates written on the instrument, the exact date is impossible to know.

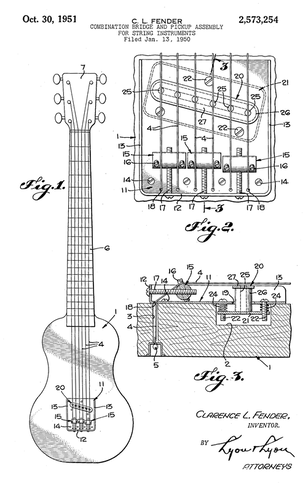

"Combination bridge and pickup assembly for string instruments" patent

"Combination bridge and pickup assembly for string instruments" patent

The first prototype had not yet been completed when Don Randall, after having been to the Chicago International Guitar League in July 1949 (for which he had, in vain, sought for a sample model to try), realized that a single pickup wasn’t enough, and asked Francis Hall to persuade Leo to build a two-pickup Spanish electric guitar to take to the NAMM in New York that August. However, at that time Leo was still purchasing dies and plates from Race & Olmsted to build the bridge plate and the pickup fiber plate, and would never have been able to complete a sample model in time to send to Don, whether with one or two pickups.

It was therefore only after these two summer events that Leo started working on the first prototype, whilst work on the second prototype was carried out in the autumn and winter of 1949, when he first started to seriously consider a two-pickup model.

By the autumn of 1949 Charlie Hayes had already received several orders for the instrument, but it remains uncertain whether he had been able to take a sample with him or whether he had only shown a few photographs around.

On 13 January 1950 Leo Fender filed a patent for a “Combination bridge and pickup assembly for string instruments”, that was approved a long time after, on 30 October 1951, with patent number 2,573,254; the first guitars were sold with a “PAT.PEND.” engraved on the bridge plate, even though the patent had not yet been approved!

It was therefore only after these two summer events that Leo started working on the first prototype, whilst work on the second prototype was carried out in the autumn and winter of 1949, when he first started to seriously consider a two-pickup model.

By the autumn of 1949 Charlie Hayes had already received several orders for the instrument, but it remains uncertain whether he had been able to take a sample with him or whether he had only shown a few photographs around.

On 13 January 1950 Leo Fender filed a patent for a “Combination bridge and pickup assembly for string instruments”, that was approved a long time after, on 30 October 1951, with patent number 2,573,254; the first guitars were sold with a “PAT.PEND.” engraved on the bridge plate, even though the patent had not yet been approved!

The Esquire

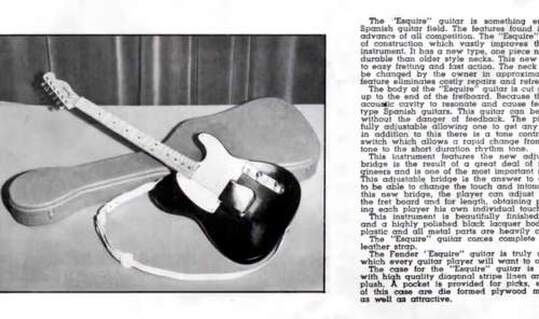

The Esquire as shown in the April 1950 catalog. It had a push pull switch and was devoid of the tring tree.

The Esquire as shown in the April 1950 catalog. It had a push pull switch and was devoid of the tring tree.

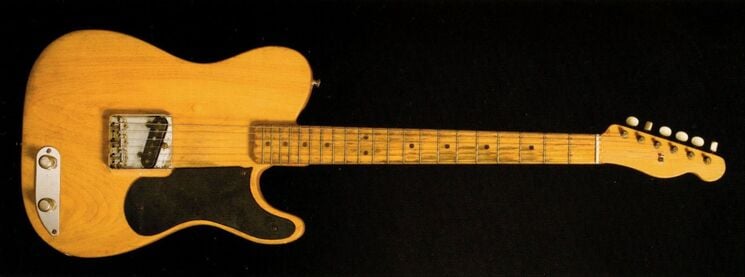

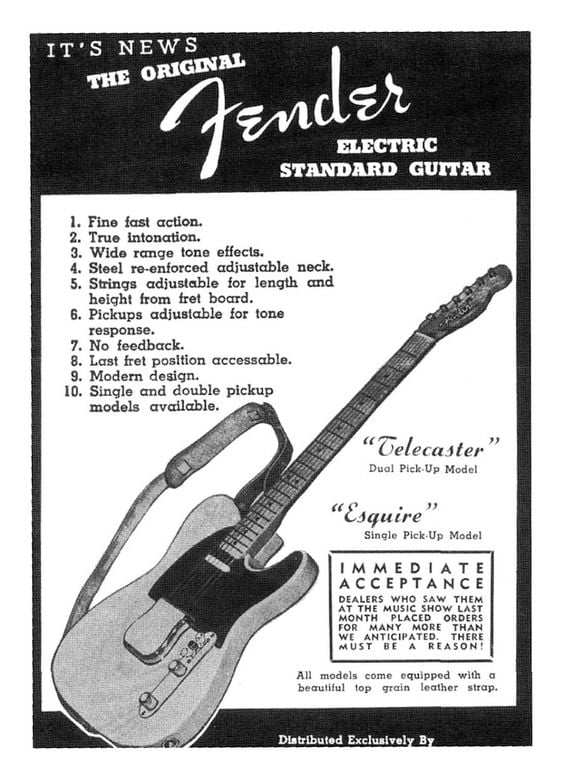

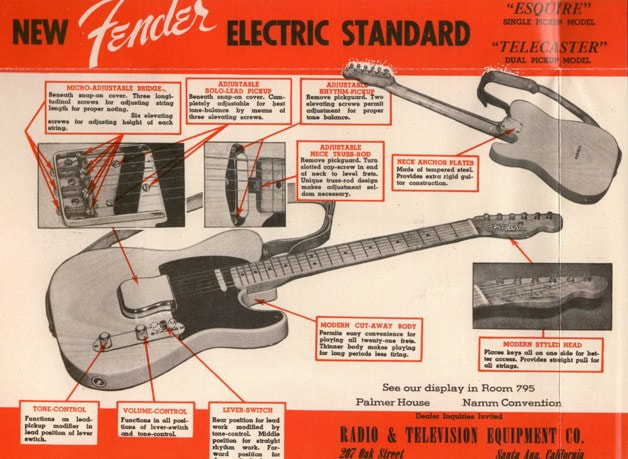

Even though it had been Don Randall himself to first suggest the manufacturing of a two-pickup guitar, and Leo had bought the die to make the bridge pickup, Don was well aware of the fact that in a closed and conservative market such as the one for musical instruments a single pickup guitar would have been cheaper and more accessible to young guitarists and, had it sold well, would have paved the way for the two-pickup model. This is why, in April 1950, Radio-Tel started promoting the single pickup solid-body guitar (which Don Randall called Esquire) on the Fender Fine Electric Instruments catalogue; in the 1980s Leo revealed that this name came across as important and set it apart from other guitar brands. The Esquire shown on the catalogue photograph was black with a white pickguard. An advert printed in May 1950 showed Jimmy Wyble with the Spade Cooley's band holding what looked like a black Esquire (most likely, however, the color had been retouched by the photographer to make it look like the one on the catalogue). In fact, other photographs taken around the same period show Jimmy Wyble and other musicians with a blonde Esquire. So why was the Esquire on the catalogue black? The very first Esquire guitars were black because black made it possible to use pine too, concealing its knots and aesthetic flaws; however, Leo quickly chose to use a blonde semitransparent color on a more eye-catching ash body, probably because this was in fashion with 1940s furniture.

If we look at the catalogue photograph carefully, we may notice two special features of the first Esquire guitars: the absence of a string tree on the headstock and the absence of the 3-way switch, with a push-pull button (similar to the one found on Organ Button lap steels guitars) in its place. In fact, the first specimen models only had two positions, and Leo probably fitted the 3-way switch on the single pickup Esquire once he’d decided to manufacture the two-pickup model too. With the 3-way switch in the first position, the electric signal reached the pickup without passing through the tone pot, in the central position the pickup was normally connected to the volume and tone, and in the third position the pickup was connected to a circuit that included a resistor and two capacitors so as to produce a sound that cut treble and which Leo called “deep rhythm”, because it allowed guitarists to play the bass parts.

The catalogue highlighted several special features of the guitar: “The new adjustable Fender bridge [...] is one of the most important modern guitar developments”, “The neck is replaceable and can be changed by the owner in approximately ten minutes”, “The guitar can be played at extreme volume without the danger of feedback”, and “The player can adjust each string for height from the fretboard and for length, obtaining perfect intonation”.

The bridge had been improved by the addition of a metal cover; often detached by guitarists and used as an ashtray (hence the term: ashtray cover).

The black pickguard, from which the term “Blackguard” given by collectors to the first Esquire guitars (and later to Broadcaster and Telecaster guitars), was attached to the body with five screws, had a different shape from that of the prototypes and extended to right under the strings.

If we look at the catalogue photograph carefully, we may notice two special features of the first Esquire guitars: the absence of a string tree on the headstock and the absence of the 3-way switch, with a push-pull button (similar to the one found on Organ Button lap steels guitars) in its place. In fact, the first specimen models only had two positions, and Leo probably fitted the 3-way switch on the single pickup Esquire once he’d decided to manufacture the two-pickup model too. With the 3-way switch in the first position, the electric signal reached the pickup without passing through the tone pot, in the central position the pickup was normally connected to the volume and tone, and in the third position the pickup was connected to a circuit that included a resistor and two capacitors so as to produce a sound that cut treble and which Leo called “deep rhythm”, because it allowed guitarists to play the bass parts.

The catalogue highlighted several special features of the guitar: “The new adjustable Fender bridge [...] is one of the most important modern guitar developments”, “The neck is replaceable and can be changed by the owner in approximately ten minutes”, “The guitar can be played at extreme volume without the danger of feedback”, and “The player can adjust each string for height from the fretboard and for length, obtaining perfect intonation”.

The bridge had been improved by the addition of a metal cover; often detached by guitarists and used as an ashtray (hence the term: ashtray cover).

The black pickguard, from which the term “Blackguard” given by collectors to the first Esquire guitars (and later to Broadcaster and Telecaster guitars), was attached to the body with five screws, had a different shape from that of the prototypes and extended to right under the strings.

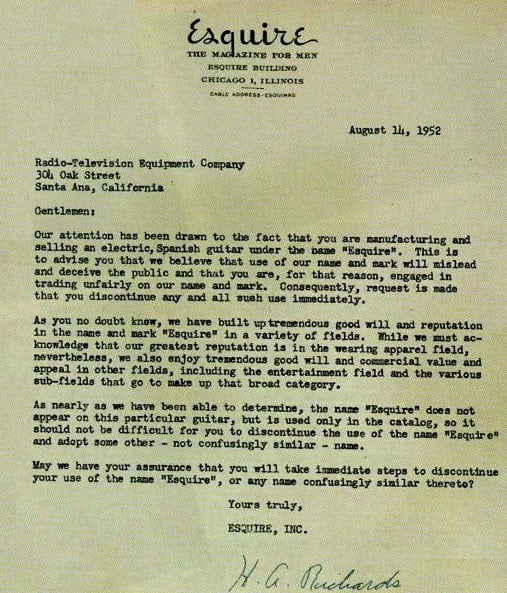

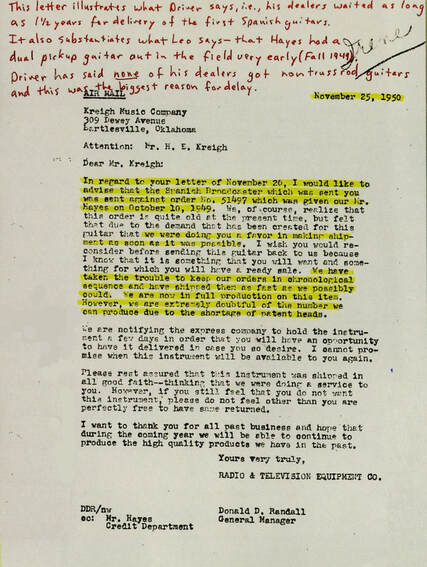

Don Randall wrote this letter, dated 25 November 1950, to the Kreigh Music Company

Don Randall wrote this letter, dated 25 November 1950, to the Kreigh Music Company

In April 1950 Charlie Hayes and Dave Driver, another Radio Tel sales representative, received their first Esquire guitars (Dave’s was black, just like the one on the catalogue) and marketing started at full steam. McCord’s Music in Dallas, which was very popular with Charlie, was also given a couple of guitars that summer. These were all “pre-production” models, because Leo was still purchasing the machines needed for full production.

It was in July 1950, during the NAMM held at Palmer House, Chicago, that most orders were received – together with important feedback from guitarists. At the show, a number of competing brand sales reps denigrated the guitar, referring to it as a “canoe paddle”, “plank”, “toilet seat with strings” and “snow shovel”, but the Esquire made a good impression with musicians and designers of other guitar brands.

No Esquire guitar was, however, shipped before the autumn of 1950; this fact is corroborated by a letter written by Don Randall to Kreigh Music Company on 25 November 1950 in response to the latter’s wish to cancel, owing to the long lead time, the order placed with Charlie Hayes on 10 October 1949 – over a year before!

It was in July 1950, during the NAMM held at Palmer House, Chicago, that most orders were received – together with important feedback from guitarists. At the show, a number of competing brand sales reps denigrated the guitar, referring to it as a “canoe paddle”, “plank”, “toilet seat with strings” and “snow shovel”, but the Esquire made a good impression with musicians and designers of other guitar brands.

No Esquire guitar was, however, shipped before the autumn of 1950; this fact is corroborated by a letter written by Don Randall to Kreigh Music Company on 25 November 1950 in response to the latter’s wish to cancel, owing to the long lead time, the order placed with Charlie Hayes on 10 October 1949 – over a year before!

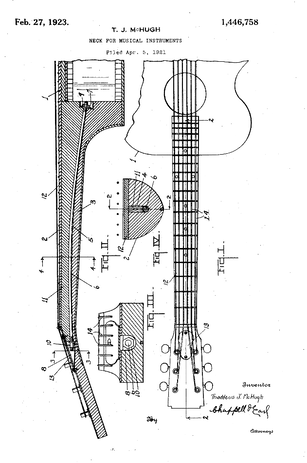

The truss rod patent by Taddeus McHugh

The truss rod patent by Taddeus McHugh

The NAMM had been crucially important because it was there that Don Randall had recognized, by talking with musicians and retailers, that a neck without a truss rod would not have provided the necessary safety and reliability. A friend of Don’s, Al Frost, suggested he use necks made of different types of laminated wood, that were more resistant than the existing ones. Don, however, was especially interested in the truss rod, whose patent, filed by Gibson’s Thaddeus McHugh in the 1920s, had recently expired.

According to several sources, Don started to insistently suggest that Leo use a truss rod, especially after the necks on a couple of Esquire guitars used as specimen models had slightly warped; a minor defect, but a very evident one to an expert’s eye, and Don feared this would put Fender in a bad light with retailers and musicians. At the NAMM Don Randall also recognized that a second pickup, fitted closer to the neck in order to play the rhythmic parts, would have been of fundamental importance to compete with other brands, but at the same time he wanted orders processed as quickly as possible because he was very concerned with how customers might have reacted to delays. Furthermore, even though Leo’s guitar was indeed a completely innovative instrument, if they had failed to flood the market with their Esquire guitars immediately other brands would have copied it, stealing all their potential customers. Every day was precious.

In the summer of 1950 Dale Hyatt sold a few “pre-production” Esquires directly to musicians, both in the shop he had purchased from Leo and at live music venues where he hanged out around Fullerton. Leo had an exclusive sales agreement with Radio-Tel and justified these sales as sample or “outlet” guitars, but Francis Hall, Don Randall and Dave Driver believed this was simply a way for Leo to make a little extra money. Two of the Esquire guitars Dale showed musicians had a defective Lead Pickup, which Leo fixed by improving the insulation between the magnets and the bobbins and inverting the phase wire with that of the ground wire.

If, on the one hand, Leo had acknowledged Dale Hyatt’s reservations concerning the defective pickups and tried to improve them, he was unable, on the other hand, to accept that his “creation” could have yet another problem. In fact, Leo was still convinced that it would have been easier to assist customers properly by replacing defective necks than by making new and more expensive ones, with a truss rod. However, when the neck of the test Esquire guitar that he himself used started warping, he realized that this could have led musicians and retailers to lose interest in the guitar, and he changed his mind.

According to several sources, Don started to insistently suggest that Leo use a truss rod, especially after the necks on a couple of Esquire guitars used as specimen models had slightly warped; a minor defect, but a very evident one to an expert’s eye, and Don feared this would put Fender in a bad light with retailers and musicians. At the NAMM Don Randall also recognized that a second pickup, fitted closer to the neck in order to play the rhythmic parts, would have been of fundamental importance to compete with other brands, but at the same time he wanted orders processed as quickly as possible because he was very concerned with how customers might have reacted to delays. Furthermore, even though Leo’s guitar was indeed a completely innovative instrument, if they had failed to flood the market with their Esquire guitars immediately other brands would have copied it, stealing all their potential customers. Every day was precious.

In the summer of 1950 Dale Hyatt sold a few “pre-production” Esquires directly to musicians, both in the shop he had purchased from Leo and at live music venues where he hanged out around Fullerton. Leo had an exclusive sales agreement with Radio-Tel and justified these sales as sample or “outlet” guitars, but Francis Hall, Don Randall and Dave Driver believed this was simply a way for Leo to make a little extra money. Two of the Esquire guitars Dale showed musicians had a defective Lead Pickup, which Leo fixed by improving the insulation between the magnets and the bobbins and inverting the phase wire with that of the ground wire.

If, on the one hand, Leo had acknowledged Dale Hyatt’s reservations concerning the defective pickups and tried to improve them, he was unable, on the other hand, to accept that his “creation” could have yet another problem. In fact, Leo was still convinced that it would have been easier to assist customers properly by replacing defective necks than by making new and more expensive ones, with a truss rod. However, when the neck of the test Esquire guitar that he himself used started warping, he realized that this could have led musicians and retailers to lose interest in the guitar, and he changed his mind.

There is, however, another version of the story to consider – one endorsed by the accounts of Geoff Fullerton, George’s son. According to Geoff, Leo never had any intention of mass producing a guitar without a truss rod, and production had not been delayed by his stubbornness concerning the truss rod but rather by all the tests carried it to ensure the guitar was perfect, by the purchase of the Race & Olmsted machines, and by the scarce availability of certain raw material. “They never intended to make Broadcaster/Telecaster without truss rod,” Geoff said. “Leo knew full well the effects of string tension, and they knew all about moisture. [...] Moisture was one of the problems Leo had had with all the warranty returns on steel guitars and cabs. [...] He was very sensitive to all these dissatisfied customers with hurt feelings. [...] They had problems with neck bowing pretty quickly, so Leo knew about that. [...] They knew they were going to have a truss rod from the beginning. George told me this, more than once. It was inconceivable that they would go into production without them. If there's a couple dozen really early guitars without truss rods, they should all be considered pre-production. [...] Look, here's Leo, a super cautious guy, he's been burned with warranty problems and bad customer relations in some cases. [...] He was very conservative. He had to be. He'd suffered losses, not only from all the warranty returns, but also from a flood in the shop. [...] A huge amount of time, money, and R&D would have to go into not only designing a truss rod but also finding an ease-of-manufacture process and making it reliable. Considering his precarious position, he did not want to jump the gun. He had to be convinced that he had the right scale length, the right neck shape, the right number of frets, the nut width - everything - before setting up tooling for neck rods. If a few guitars slipped out without truss rods, they were prototypes for display, something to take to a NAMM show or for the road reps to show dealers, or they might use them for field testing. They had meager tools, and labor was expensive, so they had to figure out a practical way to do it with the least amount of work, materials, and expense. The delays weren’t caused because Leo had to be convinced that necks needed truss rods. Delays were caused because they were figuring out how to do it.”

So how many Esquire guitars without a truss rod were ever manufactured? Richard Smith believes no more than two dozen of them were ever produced. According to Dale Hyatt, almost all necks without a truss rod warped and were replaced with new truss rod necks; and since the bodies didn’t have the groove to access the truss rod from the rhythm pickup cavity, the bodies had to be replaced too, leaving only the original hardware and electronics. Nacho Baños believes no more than thirty Esquire guitars without a truss rod were ever built, including the prototypes and sample models, all of which were black – except for perhaps a couple that had an ash body. A few years later, in 2013, in consideration of the fact that the same guitar without a truss rod had appeared on different occasions in the hands of different musicians (thus misguiding previous estimates), the number of guitars without a truss rod estimated by Smith e Baños was reduced to between ten and twenty, including the prototypes, all of which – according to Baños – were pre-production models.

So how many Esquire guitars without a truss rod were ever manufactured? Richard Smith believes no more than two dozen of them were ever produced. According to Dale Hyatt, almost all necks without a truss rod warped and were replaced with new truss rod necks; and since the bodies didn’t have the groove to access the truss rod from the rhythm pickup cavity, the bodies had to be replaced too, leaving only the original hardware and electronics. Nacho Baños believes no more than thirty Esquire guitars without a truss rod were ever built, including the prototypes and sample models, all of which were black – except for perhaps a couple that had an ash body. A few years later, in 2013, in consideration of the fact that the same guitar without a truss rod had appeared on different occasions in the hands of different musicians (thus misguiding previous estimates), the number of guitars without a truss rod estimated by Smith e Baños was reduced to between ten and twenty, including the prototypes, all of which – according to Baños – were pre-production models.

THE DUAL PICKUP ESQUIRE AND THE BROADCASTER

Dual Pickup Esquire

Sam Hutton with his "pre-production" dual pickup Esquire, January 1994. This guitar had 0009 serial number and its pine body was refinshed in red. The pickup was a lap steel one and the non-truss rod neck is slightly longer.

Sam Hutton with his "pre-production" dual pickup Esquire, January 1994. This guitar had 0009 serial number and its pine body was refinshed in red. The pickup was a lap steel one and the non-truss rod neck is slightly longer.

The model Leo most wanted to manufacture was the two-pickup one, totally ignoring all the marketing effort that had been carried out by Radio-Tel and, above all, the orders booked by sales reps for the single pickup Esquire. In fact, once Leo got fixated on something, it was hard to change his mind, and the retailers that had insisted on having the cheaper single pickup model were now forced to wait for the new guitar to enter full production, between December 1950 and January 1951, and have it shipped to them in February. Moreover, Leo didn’t give particular importance to the color of the Esquires to be shipped and instead of manufacturing black ones, like the one on the catalogue, opted for blonde!

Esquire production bodies made after early 1951 had cavities for both pickups, whether single or dual pickups: indeed, it is difficult to imagine how it would have been either efficient or economic for Leo to manufacture two different bodies, each with its own routing.

The Rhythm Pickup, fitted close to the neck, had been developed in the spring of 1950 and featured a slightly smaller bobbin and a metal cover. On 22 June Leo purchased the die to make the top and bottom neck pickup fiber plates and on 26 July the one to make its metal cover, which Leo believed was necessary to cut the higher pitch harmonics, and the one to make the 3-way switch control plate.

Dual Pickup Esquire guitars had a 3-way switch, a volume knob and a “blend” knob – used to mix the neck pickup with the bridge pickup in the lead position. Surprisingly, therefore, there was no tone control. In the lead switch position the blend knob would mix the neck pickup with the bridge pickup, in the central switch position only the neck pickup was activated, with no tone control, whilst the third switch position activated the neck pickup (again without tone control), but this time the signal travelled through a capacitor which cut treble to give the “deep rhythm” effect. This wiring continued to be used on two-pickup Fenders until around the end of 1952, when Leo replaced the blend with a real tone control, thus eliminating combinations between the two pickups.

The first Dual Pickup Esquire guitars were recognizable both by the absence of a truss rod and routing on the body, between the neck pocket and the rhythm pickup (made to make truss rod adjustment easier), and the absence of the string tree on the headstock.

Even though not advertised, a pre-production Dual Pickup Esquire guitar (without a truss rod) had probably already been built in Fullerton before the summer of 1950; however, even if Don Randall had taken the guitar to Chicago, it was never exhibited and always stayed behind-the-scenes.

Esquire production bodies made after early 1951 had cavities for both pickups, whether single or dual pickups: indeed, it is difficult to imagine how it would have been either efficient or economic for Leo to manufacture two different bodies, each with its own routing.

The Rhythm Pickup, fitted close to the neck, had been developed in the spring of 1950 and featured a slightly smaller bobbin and a metal cover. On 22 June Leo purchased the die to make the top and bottom neck pickup fiber plates and on 26 July the one to make its metal cover, which Leo believed was necessary to cut the higher pitch harmonics, and the one to make the 3-way switch control plate.

Dual Pickup Esquire guitars had a 3-way switch, a volume knob and a “blend” knob – used to mix the neck pickup with the bridge pickup in the lead position. Surprisingly, therefore, there was no tone control. In the lead switch position the blend knob would mix the neck pickup with the bridge pickup, in the central switch position only the neck pickup was activated, with no tone control, whilst the third switch position activated the neck pickup (again without tone control), but this time the signal travelled through a capacitor which cut treble to give the “deep rhythm” effect. This wiring continued to be used on two-pickup Fenders until around the end of 1952, when Leo replaced the blend with a real tone control, thus eliminating combinations between the two pickups.

The first Dual Pickup Esquire guitars were recognizable both by the absence of a truss rod and routing on the body, between the neck pocket and the rhythm pickup (made to make truss rod adjustment easier), and the absence of the string tree on the headstock.

Even though not advertised, a pre-production Dual Pickup Esquire guitar (without a truss rod) had probably already been built in Fullerton before the summer of 1950; however, even if Don Randall had taken the guitar to Chicago, it was never exhibited and always stayed behind-the-scenes.

Broadcaster

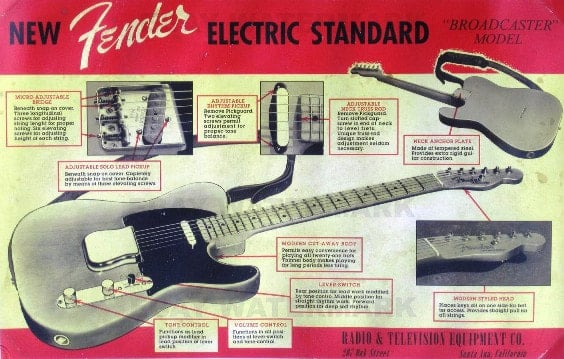

Broadcaster advertising insert printed to complement the 1950 catalog in the latter part of the year. It was used also for the February 1951 Musical Merchandise issue.

Broadcaster advertising insert printed to complement the 1950 catalog in the latter part of the year. It was used also for the February 1951 Musical Merchandise issue.

Leo bought the machine to make the truss rod from Race & Olmsted on 3 October 1950 and production started at the end of the month. Innovative, as always, Leo had devised a new technique to insert the truss rod in the neck by making a longitudinal incision on the back of the neck, subsequently filled with a strip of walnut. The characteristic look that this gave the neck of the guitar earned it the nickname skunk stripe. The reinforced necks could also be recognized by the small tear-shaped plug on the headstock, nicknamed walnut plug, which covered the fastening point of the truss rod. However, for aesthetic reasons, Leo preferred using maple as the filling wood on the very first guitars; these guitars thus appeared not to have a truss rod.

Don Randall had decided to call the two-pickup truss rod model Broadcaster because radio broadcasting was very popular in the 1940s: “For Leo Fender's first smash guitar, I thought and thought about what to call it. I finally decided to use something that had to do with broadcasting. I named it Broadcaster”.

The first flyers promoting the Broadcaster guitar were published in a magazine at the end of 1950, as an addition to the catalogue, and in February 1951 on Musical Merchandise.

Don Randall had decided to call the two-pickup truss rod model Broadcaster because radio broadcasting was very popular in the 1940s: “For Leo Fender's first smash guitar, I thought and thought about what to call it. I finally decided to use something that had to do with broadcasting. I named it Broadcaster”.

The first flyers promoting the Broadcaster guitar were published in a magazine at the end of 1950, as an addition to the catalogue, and in February 1951 on Musical Merchandise.

The time had come to speed up production. One of the problems Leo faced was the shortage of raw materials, such as cobalt contained in the pickups or chrome used in the hardware. These shortages were caused by the rationing of raw materials effective from 1 September 1950 as a result of the war in Korea, which had started only a few months earlier. Delays were also due, however, to Leo’s perfectionist nature and to all the tests he carried out. For example, he first tried laminated pine bodies, then chambered ones, then went back to pine again, and finally solid-body ash ones. Leo also tried different finishes: first white, then black, finally blonde. We should also not forget that Leo did not initially have much money and was only able to purchase the machines he needed for large-scale production a bit at a time.

87 Broadcaster guitars were sold in January 1951 and 65 were sold in February.

87 Broadcaster guitars were sold in January 1951 and 65 were sold in February.

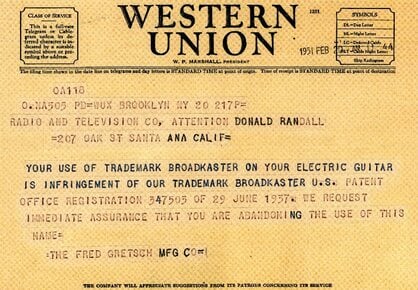

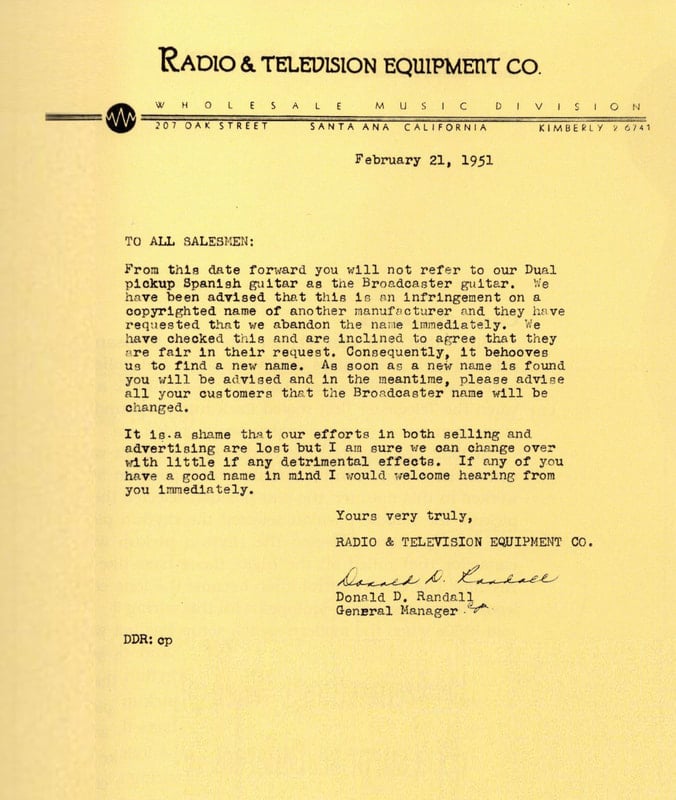

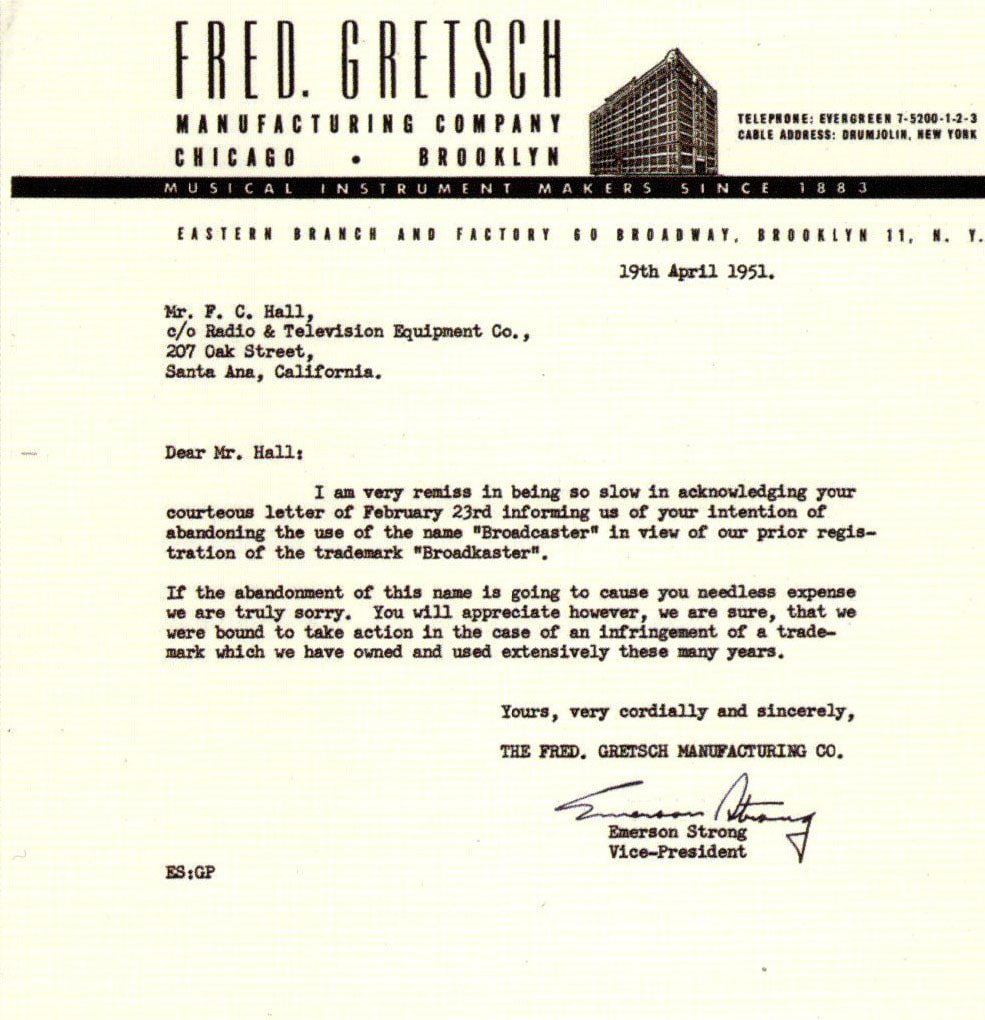

FROM THE BROADCASTER TO THE TELECASTER

On 20 February 1951 a telegram sent by Gretsch ordered Fender to stop using the Broadcaster name since it infringed their Broadkaster (with a “k”) line of drums registered trademark. Don immediately warned his reps to stop using the name, whilst Francis Hall wrote to Gretsch advising that they were not aware of the trademark, thanking Gretsch for having warned them before production had reached full-capacity and promising to destroy all advertising flyers. Meanwhile, Leo and his workers started removing the “Broadcaster” decal from the headstocks of all dual pickup guitars in the factory, leaving only the “Fender” decal. The guitars that were sold in those first few months (until around August), without a name on the headstock, are nowadays referred to by collectors as “Nocaster” guitars.

After receiving the opinion of Robert D. Pearson, a Los Angeles attorney specialized in registered trademarks, so as to be sure of not infringing any other trademark, Don called the dual pickup model Telecaster, because televisions were becoming very popular in the 1950s. In fact, a Tele Caster trademark registered by Packard-Bell for one of its television sets had existed before, but had by then expired. The advertising insert in the June issue of Musical Merchandise clearly referred to the dual pickup model with the name “Telecaster”, even though, if one looks at the photograph carefully, the guitar was in fact a Broadcaster with the decal removed.

Interestingly, from 1951 to 1953 various telegrams from the Esquire Magazine For Men were also received, asking Fender to cease the use of the Esquire name, too! However, Don Randall never cared about them and the Esquire was produced until 1969, when it was discontinued.

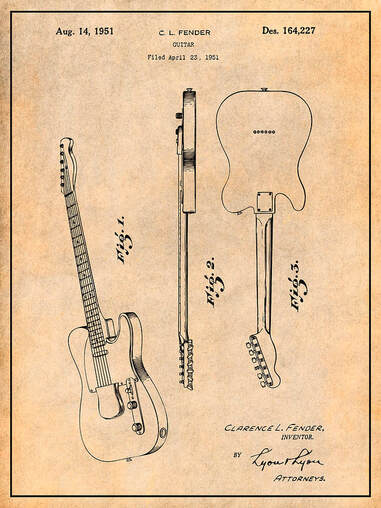

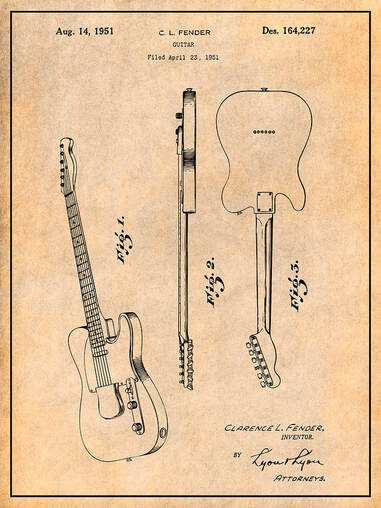

What Leo patented was the original and innovative design of his guitar

What Leo patented was the original and innovative design of his guitar

On 23 April 1951 Leo filed a patent for his solid-body guitar. The patent was approved on 14 August that year, with patent number “Des. 164,227”, where “Des.” stood for design. In fact, examining the patent carefully, one can notice that there is no written reference to the Esquire or Telecaster; what Leo filed was the original and innovative design of his guitar. Indeed, there could have been no reference to the headstock (see what has been said above in relation to Croatian musicians) nor to the bolt-on neck (this had already been used by the Rickenbacker). Even the 25.5” scale length, which was longer than that of the Gibson and Merle Travis guitars and which Leo liked for the sound it gave the guitar, was already used by Gretsch. Nevertheless, Leo Fender had managed to improve everything and to invent a new way of assembling electric guitars on a large scale. As Leo said, success does not necessarily lie in inventing something completely new, but also in perfecting an existing project.

From 1951 many guitarists turned to Fender as their first-choice guitar, and Fender set itself apart in the extremely conservative world of guitars. Its golden age had started.

From 1951 many guitarists turned to Fender as their first-choice guitar, and Fender set itself apart in the extremely conservative world of guitars. Its golden age had started.