BILL SCHULTZ E DAN SMITH

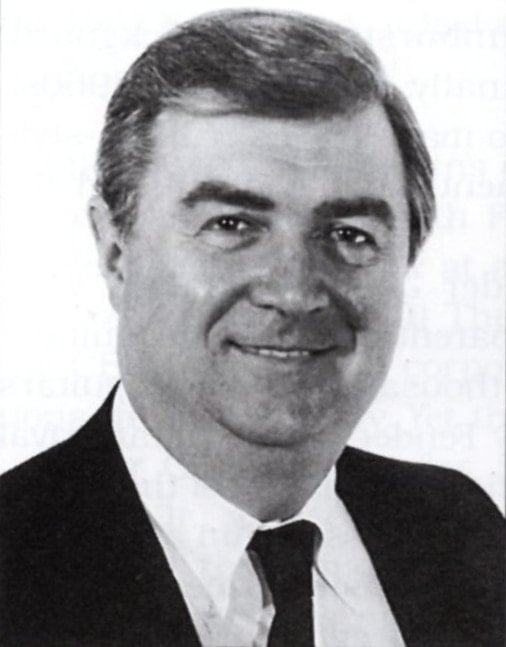

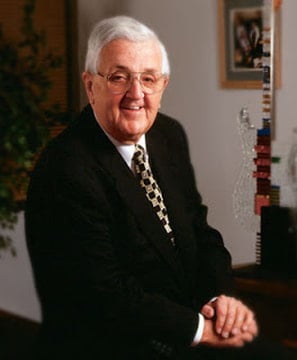

I quindici anni di gestione CBS portarono inevitabilmente alla distruzione di tutto quello che Leo Fender era riuscito faticosamente a costruire. Indebolita dalla cattiva reputazione che si era fatta e dall'interesse del pubblico verso le Stratocaster vintage, la CBS cercò nuove persone per riportare in auge l'azienda. Nel 1981 la CBS assunse John McLaren per dirigere l'intera divisione CBS Musical Instruments - che includeva Steinway, Gemeinhardt, Lyon & Healy harps, Gulbransen. John era inglese, di Manchester, e proveniva dalla Yamaha. Nello stesso anno John rimpiazzò Ed Llewellyn con Bill Schultz, anch'egli proveniente dalla Yamaha, come presidente della Fender/Rodgers/Rhodes.

Bill era un brillante uomo d'affari. Avrebbe dovuto riprogettare la Fender, migliorarne la qualità dei prodotti e la nomea e rinvigorirne la produzione e la rete di vendita attraverso le difficoltà della nuova economia globale.

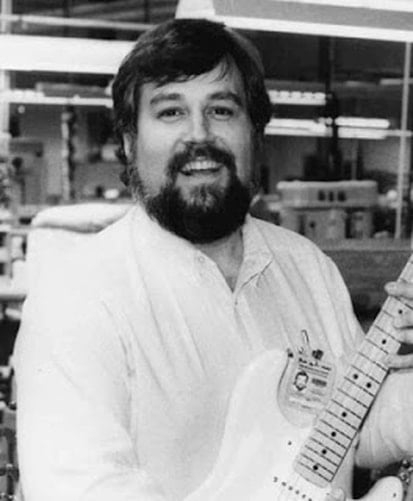

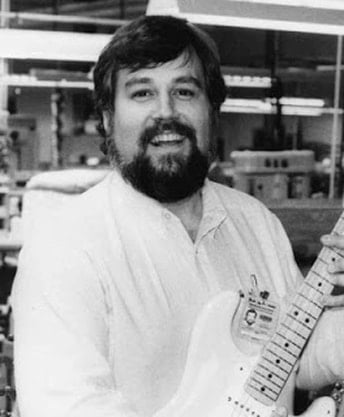

Era ovvio che la Stratocaster doveva essere "de-CBSizzata". E non bastavano nuovi colori, nuove combinazioni sonore o componenti in ottone, serviva ben altro: la chitarra simbolo della Fender doveva essere messa in discussione ed essere ridisegnata dall'inizio alla fine. L'uomo adatto per questo scopo era, per Bill Schultz, un designer proveniente ancora dalla Yamaha che assunse nel 1981: Dan Smith.

Dan era molto carismatico, sapeva parlare con le persone e, a volte, sapeva ispirarle. Aveva una grande passione per la Fender ed era amato dai suoi dipendenti. Di sicuro fu la persona più importante per la Fender dai tempi di Leo. Senza di lui probabilmente oggi la Fender non esisterebbe. «And at that point in time everybody hated what Fender had become. For about 10 years, the quality of the product had been awful. Not that there weren’t good guitars made during that time, but generally it had really gone down», disse Dan Smith. «The company had no soul at the top. When I first came there, I sat down and talked to guys like John Page and Troy Lane and some of the guys working on the line, and the players who worked for the company were really unhappy. They’d come to work for Fender because it had been a dream of theirs as kids to work for a guitar company, and they came in and they cared about the quality of the product. But the management at that time could really give a shit». E, a proposito della fabbrica di Fullerton: «Everything was antiquated. We had come from Yamaha — and at that point Yamaha probably had the most modern guitar factory in the world, for both acoustics and electrics — into a factory where guys were hand-cutting on a bandsaw with no guards, cutting out the contours. They’d have a thing they’d lay on top of it as a guide, they’d put a pencil mark on the back and a pencil mark on the front, they’d lay it into a tray, and the bandsaw blade was exposed so much. If that blade had snapped or something like that, the guy’d be dead».

In The Fender Telecaster: The Detailed Story Of America’s Senior Solid Body Electric Guitar, André R. Duchossoir riportò quanto dichiarato da Dan Smith: «Basically our goal was initially to restore the confidence of the dealers and the players in Fender. The only way we could achieve that was to raise the quality levels back up! We basically shut the plant down and retaught everybody how to make Fender guitars the way people wanted them».

Con il contributo di illustri “interni” alla Fender, tra cui John Page, Dan Smith iniziò a introdurre una serie di cambiamenti e, dopo la necessaria riorganizzazione dell’azienda e la riqualificazione dei dipendenti, puntando molto sulla Ricerca & Sviluppo la Fender iniziò la sua rinascita.

Sotto la guida di Dan Smith non solo la Stratocaster fu rivisitata completamente, ma il listino si arricchì di nuove chitarre, tra cui le riedizioni del '57 e del '62, chiamate Vintage Stratocaster, e la Fender iniziò a produrre per la prima volta delle chitarre al di fuori degli Stati Uniti, iniziando l'epoca del Made in Japan.

Bill era un brillante uomo d'affari. Avrebbe dovuto riprogettare la Fender, migliorarne la qualità dei prodotti e la nomea e rinvigorirne la produzione e la rete di vendita attraverso le difficoltà della nuova economia globale.

Era ovvio che la Stratocaster doveva essere "de-CBSizzata". E non bastavano nuovi colori, nuove combinazioni sonore o componenti in ottone, serviva ben altro: la chitarra simbolo della Fender doveva essere messa in discussione ed essere ridisegnata dall'inizio alla fine. L'uomo adatto per questo scopo era, per Bill Schultz, un designer proveniente ancora dalla Yamaha che assunse nel 1981: Dan Smith.

Dan era molto carismatico, sapeva parlare con le persone e, a volte, sapeva ispirarle. Aveva una grande passione per la Fender ed era amato dai suoi dipendenti. Di sicuro fu la persona più importante per la Fender dai tempi di Leo. Senza di lui probabilmente oggi la Fender non esisterebbe. «And at that point in time everybody hated what Fender had become. For about 10 years, the quality of the product had been awful. Not that there weren’t good guitars made during that time, but generally it had really gone down», disse Dan Smith. «The company had no soul at the top. When I first came there, I sat down and talked to guys like John Page and Troy Lane and some of the guys working on the line, and the players who worked for the company were really unhappy. They’d come to work for Fender because it had been a dream of theirs as kids to work for a guitar company, and they came in and they cared about the quality of the product. But the management at that time could really give a shit». E, a proposito della fabbrica di Fullerton: «Everything was antiquated. We had come from Yamaha — and at that point Yamaha probably had the most modern guitar factory in the world, for both acoustics and electrics — into a factory where guys were hand-cutting on a bandsaw with no guards, cutting out the contours. They’d have a thing they’d lay on top of it as a guide, they’d put a pencil mark on the back and a pencil mark on the front, they’d lay it into a tray, and the bandsaw blade was exposed so much. If that blade had snapped or something like that, the guy’d be dead».

In The Fender Telecaster: The Detailed Story Of America’s Senior Solid Body Electric Guitar, André R. Duchossoir riportò quanto dichiarato da Dan Smith: «Basically our goal was initially to restore the confidence of the dealers and the players in Fender. The only way we could achieve that was to raise the quality levels back up! We basically shut the plant down and retaught everybody how to make Fender guitars the way people wanted them».

Con il contributo di illustri “interni” alla Fender, tra cui John Page, Dan Smith iniziò a introdurre una serie di cambiamenti e, dopo la necessaria riorganizzazione dell’azienda e la riqualificazione dei dipendenti, puntando molto sulla Ricerca & Sviluppo la Fender iniziò la sua rinascita.

Sotto la guida di Dan Smith non solo la Stratocaster fu rivisitata completamente, ma il listino si arricchì di nuove chitarre, tra cui le riedizioni del '57 e del '62, chiamate Vintage Stratocaster, e la Fender iniziò a produrre per la prima volta delle chitarre al di fuori degli Stati Uniti, iniziando l'epoca del Made in Japan.

Antonio Calvosa