Since Leo’s time, Hispanic workers, like the famous Tadeo Gomez, Lilly Sanchez or Abigail Ybarra, had always been employed in Fender factories, so that the opening of the Mexican plant should not be surprising, mainly because it was only 200 miles from the US Corona factory.

Already during the CBS era, Fender had used Mexican firms for packing and making strings. After the 1985 buyout, Bashar Darcazallie, a Fender engineer, went to Mexico and, on May 6, 1987, arranged the string manufacturing with five employees in a converted church in Ensenada, Baja California.

However, Bill Schultz realized soon the possibility to develop an instruments manufacturing facility in Mexico, and, in 1989, the factory was moved from its original site to the location it still occupies today, on Calle Huerta, where the production of amplifier sub-assemblies started.

Already during the CBS era, Fender had used Mexican firms for packing and making strings. After the 1985 buyout, Bashar Darcazallie, a Fender engineer, went to Mexico and, on May 6, 1987, arranged the string manufacturing with five employees in a converted church in Ensenada, Baja California.

However, Bill Schultz realized soon the possibility to develop an instruments manufacturing facility in Mexico, and, in 1989, the factory was moved from its original site to the location it still occupies today, on Calle Huerta, where the production of amplifier sub-assemblies started.

A key role in the development of this factory was played by the Japanese Fujigen, which made the F&F joint venture with Fender Musical Instruments Corporation.

Fender CEO Bill Mendello, interviewed in 2011, remembered: “Fujigen brought their machinery with them, plus five or six people. We opened up our Mexican operation, and Fujigen trained the people, using their techniques. So the manufacture of guitars in Mexico was more Japanese-like than it was US-like. We had a few people from USA help them, but for the most part the training, the techniques, the painting, all were Japanese.”

The agreement was that FMIC would supply the building and the money, whilst Fujigen would supply the building techniques and the machinery. At first, everything in Ensenada was directed by Fujigen, not by Fender USA. All the foremen and Department Supervisors were Japanese, but upper management, President, factory manager were all Fender.

The joint venture was dissolved in late 1994 when Fender bought out Fujigen’s interest. The 1993 yen and dollar shift hurt Fujigen a lot and they hung on until 1994, when their president finally decided to sell their shares.

Fender CEO Bill Mendello, interviewed in 2011, remembered: “Fujigen brought their machinery with them, plus five or six people. We opened up our Mexican operation, and Fujigen trained the people, using their techniques. So the manufacture of guitars in Mexico was more Japanese-like than it was US-like. We had a few people from USA help them, but for the most part the training, the techniques, the painting, all were Japanese.”

The agreement was that FMIC would supply the building and the money, whilst Fujigen would supply the building techniques and the machinery. At first, everything in Ensenada was directed by Fujigen, not by Fender USA. All the foremen and Department Supervisors were Japanese, but upper management, President, factory manager were all Fender.

The joint venture was dissolved in late 1994 when Fender bought out Fujigen’s interest. The 1993 yen and dollar shift hurt Fujigen a lot and they hung on until 1994, when their president finally decided to sell their shares.

At first, due to the proximity between Corona and Ensenada, there was such an exchange of human resources and components, that a guitar born in the US was often completed in Mexico, and, consequently, defining the nationality of a Stratocaster was very difficult. Some Stratocasters built in Mexico in the '90s, such as the “California”, could indeed be considered USA/MEXICO hybrid instruments.

The first guitars with the “MADE IN MEXICO” decal appeared on catalogsas early as 1991. They were not only Stratocasters made to Fender's specs, like the Squiers, but authentic Fenders made by Fender workers using Fender machinery, so that now it was possible to buy a quality Stratocaster at an affordable price, though the top of the production was still American, since the better woods and components remained in the US.

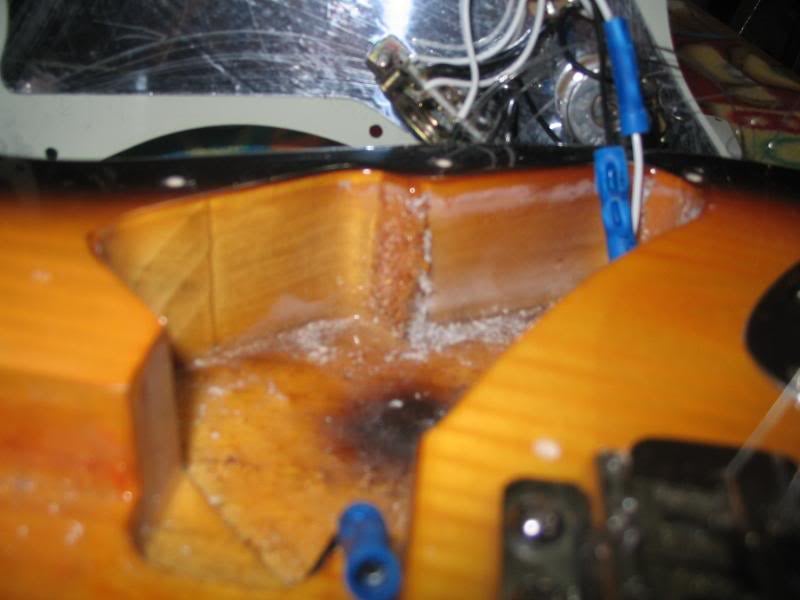

On the evening of February 11, 1994, a routine maintenance procedure in a spray booth at Ensenada factory resulted in devastating fire. A spark that found its way into a spray booth vent erupted in flames that reduced the 22,000-square-foot factory to ashes in less than one hour.

As President Bill Shultz recalls: “We were relieved that none of our employees sustained injuries, but the instantaneous destruction of the years of work that went into establishing this plant was overpowering”. However, in less than a hundred days Fender built a new factory twice the size of the previous one: “Fender's ability to so quickly rebound from this disaster is a strong testimony to our quality workforce in Mexico, for without their help, assistance, and understanding, this accomplishment would not have been possible,” Bill declared.

According to Mike Lewis, the new enlarged Ensenada factory would have been able to manufacture more guitars: “We had recently built our new factory in Mexico, following a bad fire in 1994, and so I had brought a lot of Fender guitars into what was now our own manufacturing plant. That's why many Japanese guitars disappeared and went into Mexico: the Fender Classic scries was made in Mexico, for example. We did a lot of things to bring guitars into our own manufacturing plant.”

The first guitars with the “MADE IN MEXICO” decal appeared on catalogsas early as 1991. They were not only Stratocasters made to Fender's specs, like the Squiers, but authentic Fenders made by Fender workers using Fender machinery, so that now it was possible to buy a quality Stratocaster at an affordable price, though the top of the production was still American, since the better woods and components remained in the US.

On the evening of February 11, 1994, a routine maintenance procedure in a spray booth at Ensenada factory resulted in devastating fire. A spark that found its way into a spray booth vent erupted in flames that reduced the 22,000-square-foot factory to ashes in less than one hour.

As President Bill Shultz recalls: “We were relieved that none of our employees sustained injuries, but the instantaneous destruction of the years of work that went into establishing this plant was overpowering”. However, in less than a hundred days Fender built a new factory twice the size of the previous one: “Fender's ability to so quickly rebound from this disaster is a strong testimony to our quality workforce in Mexico, for without their help, assistance, and understanding, this accomplishment would not have been possible,” Bill declared.

According to Mike Lewis, the new enlarged Ensenada factory would have been able to manufacture more guitars: “We had recently built our new factory in Mexico, following a bad fire in 1994, and so I had brought a lot of Fender guitars into what was now our own manufacturing plant. That's why many Japanese guitars disappeared and went into Mexico: the Fender Classic scries was made in Mexico, for example. We did a lot of things to bring guitars into our own manufacturing plant.”

Among the first Mexican series should be remembered the Standard Series (whose predecessor, the Standard Stratocaster, was the cheap answer to the American Standard), the Special Series and the Deluxe Series, in addition to the varied vintage style guitars, like the Classic Series, the Road Worn or the vintage/modern hybrids, like the Classic Player Series, all replaced by Vintera Series, and the many Artist guitars.

Antonio Calvosa